Lidwina of Schiedam and the oldest skating image in the Netherlands

Nelly Moerman, author

Cis van Heertum, English translation

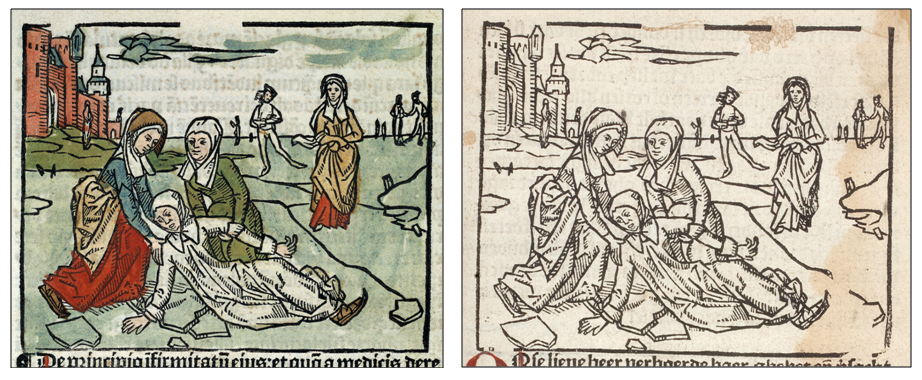

The oldest skating image in the Netherlands is a woodcut depicting Lidwina of Schiedam’s fall on the ice. She is lying on her right side, her face contorted with pain, while the skate on her left foot is still visible. Two friends have knelt down by her and try to help her up. The woman on the left can also be seen wearing skates on both feet. They are not ordinary skates, however. In Dutch they are known as ‘prikschaatsen’, skates that have an iron blade with a sharp spike close to the toe. A suitable English equivalent of the Dutch word ‘prikschaats’ might be ‘spiked skate’.

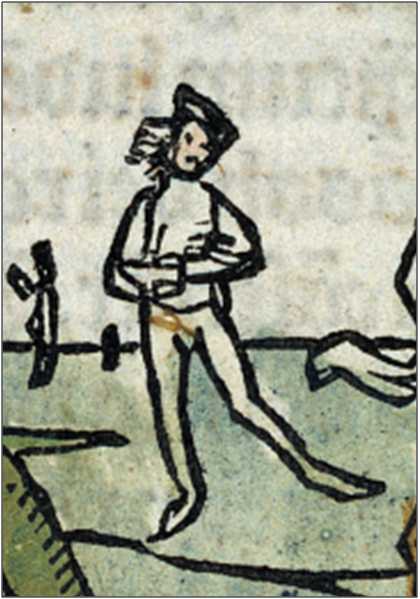

Depicted in the background in the middle is an elegantly skating man, moving upright, arms folded, skating with one leg stretched out in the typical position of a ‘Dutch roll’.

Lidwina’s history

What do we know about Lidwina of Schiedam? Her name is spelt in several ways. My Master’s research on the Lidwina woodcuts yielded 122 variants of the name (Moerman 2012; pp. 8-10 and appendix I). Common variants are: Liduina, Lidwina, Liedwy, Lydwine, Lydewy. Lidwina was born in Schiedam in 1380 and lived in that city until her death in 1433. She grew up in a family of nine, the only girl among four elder and four younger brothers.

When she was about fifteen years old she and her friends went skating. She landed so badly on a fragment of ice that she broke a short rib in her right side. It caused an abscess to develop that ruptured inwards, leading to one illness after the other. She never recovered and would remain bedridden all her life. When she died at the age of 53, she had been confined to her sickbed for 38 years.

Lidwina, protector of Schiedam

Lidwina’s life was already described soon after her death. The best known biography is that of Johannes Brugman: the Vita alme virginis Lijdwine (The Life of the Blessed Virgin Lijdwine). Brugman wrote his text in Latin in 1456. It was printed in Schiedam in 1498 by Otgier Nachtegael, a local priest. The motive for a printed edition of her life was a miracle that Lidwina was supposed to have performed. It was thought that when enemy troops were planning to attack Schiedam, Lidwina caused the trumpeter to sound the signal for the assault two hours too early. Forewarned, the inhabitants of Schiedam were thus able to avert the attack. Lidwina had saved the city of Schiedam and the grateful citizens wanted to keep her story alive.

Damage to the woodcut of The Fall on the Ice in the reprint

Otgier Nachtegael printed a fine edition of Brugman’s text with a series of twenty woodcuts chronicling events from her life. One of those woodcuts is ‘The Fall on the Ice’. Otgier Nachtegael reused the woodcut series for a Middle Dutch edition seven years later in 1505. By then, the woodcut depicting the fall on the ice had suffered damage on the right.

This is obvious from the skate on Lidwina’s foot. The line of the iron blade in the woodcut of the 1505 edition shows some irregularities at the front and is no longer smoothly curved as in the original 1498 impression.

Museum Catharijneconvent Utrecht.

Providing food and clothing for the poor

Brugman narrates several aspects of Lidwina’s life in his Vita. She endured all her illnesses with dignity. In spite of her own suffering she never lost interest in those around her. She cared for her fellowmen and organized the distribution of food and clothing to the poor from her sickbed. Prominent rulers and scholars such as John. Duke of Bavaria and Wermbold van Boskoop travelled to Schiedam to speak with her. When Margaretha, Countess of Holland, visited Schiedam and was told about Lidwina’s long-standing illnesses, she sent her personal physician Govaert Sonderdanc to see if he could help.

Veneration by the local population

The local population always felt a deep veneration for Lidwina. She was regarded as a saint already during her lifetime, and there were several attempts to have her canonized. Only in 1890, however, did Pope Leo XIII confirm her sainthood, after centuries of popular veneration. The recognition of her sanctity turned her into an official saint. Lidwina has become the patron saint of the chronically ill, and as ‘saint of skating’ she is invoked for help and support by skaters.

References

Source

© Nelly Moerman 2016, 2019

This article is protected by copyright. Reproduction of the text, in whole or in part, is permitted only on an individual basis and under the conditions of acknowledgement of source and correct citation. In case of a financial interest or the pursuit of such an interest, copying is not allowed. In case of doubt, please contact the author.

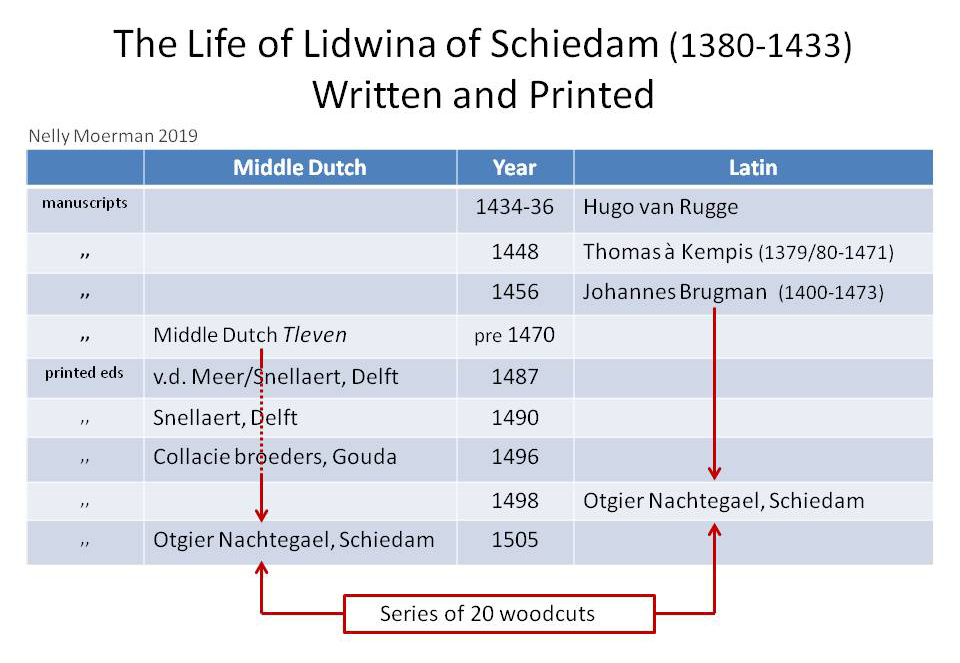

The Life of Lidwina of Schiedam Written and Printed

Nelly Moerman, author

Cis van Heertum, English translation

At the time Lidwina of Schiedam (1380-1433) lived, texts were written by hand, often in Latin. The copying of texts usually took place in convents and by religious communities. Many of these manuscripts, however, have been lost in the course of time, so that researchers wishing to study the original texts must often content themselves with copies of a later date. This is also the case for the Life of Lidwina of Schiedam. The original Vitae Sanctorum (Saints’ Lives) are often only available as later copies.

Manuscript Vitae

Not long after Lidwina’s death in 1433 Hugo van Rugge wrote a biography in Latin (1434-1436). The text has become known by the opening words: Venite et Videte (Come and See). Thomas à Kempis provided an improved version in 1448 under the title Vita Lidewigis. A third biography in Latin was written by Johannes Brugman, who delivered his Vita alme virginis Lijdwine (The Life of the Blessed Virgin Lijdwine) in 1456. Brugman described her life as an ascent towards holiness. He added new elements to his story and made use of previously unknown sources.

A Middle Dutch version which has become known as Tleven was also composed in the fifteenth century, before 1470. It was long thought that the author was Jan Gerlach, but Koen Goudriaan (2003) has demonstrated persuasively that this is not the case. By comparing copies of the two texts of Venite and Tleven in a detailed study, he came to the conclusion that the Middle Dutch Tleven is an abridged version of Hugo van Rugge’s Latin Venite et Videte.

Printed proof of Lidwina’s popularity

After the art of printing had been invented in the second half of the fifteenth century, it became a lot easier to disseminate texts. Three Middle Dutch editions of Lidwina’s life appeared in Delft and Gouda within less than ten years (1487-1496). It shows how great the interest was in editions of her story in the vernacular. Lidwina must have been exceedingly popular with the people in those days. In 1497 the church wardens of Schiedam also wanted to have a book printed chronicling the life of Lidwina, though this time in Latin. The book was intended as an acknowledgement that Schiedam had been rescued from an enemy attack by Lidwina. It might also have helped raise money to finance an appeal for canonization in Rome. The church wardens chose the text Brugman had written in 1456. The printer was Otgier Nachtegael, a local priest. A printing press was set up especially for the occasion at the Saint Anna convent in Schiedam. To embellish the book, twenty woodcuts were added depicting events in Lidwina’s life (1498). Seven years later (1505) Otgier Nachtegael reused the same woodcuts for an edition in the vernacular. By then, the woodcut showing Lidwina’s fall on the ice had become damaged on the right. (See: ‘Lidwina of Schiedam and the oldest skating image in the Netherlands’)

Late Middle Ages and everyday life

How does the life story of a Vita fit in with life as it was lived in the Late Middle Ages? Goudriaan states in his article (2003 p.179) that the ‘Lives of saints are always (re)constructions.’ Speaking of Hugo van Rugge and Thomas à Kempis he adds: ‘The Lidwina we encounter in their Vitae is modelled after the ideal of the authors, blocking access to the “historical” Lidwina.’ Stories about Lidwina were already written during her lifetime. Historical verification of the facts remains a possibility, even though it will never be complete and definitive.

References

1. Nelly Moerman, ‘In hout gesneden. Verbeelding en beeldtraditie in Het leven van Liduina van Schiedam’, in: Beelden van Liduina: Heilige van Schiedam, Schiedam (2015) 77-88. (Adapted version of an article published in Madoc including the visual tradition and colour images)

2. Charles Caspers & Rijcklof Hofman, Een bovenaardse vrouw. Zes eeuwen verering van Liduina van Schiedam / Het leven van de heilige maagd Liduina, Hilversum 2014.

3. Nelly Moerman, ‘In hout gesneden. Verbeelding en beeldtraditie in Het leven van Lidwina van Schiedam', Madoc: tijdschrift over de Middeleeuwen, 27:1 (2013) 34-42.

4. Nelly Moerman, Lidwina van Schiedam nader bekeken. Houtsneden in vroege drukken, Amsterdam 2012 [MA thesis].

5. Koen Goudriaan, ‘Het Leven van Liduina en de Moderne Devotie’, in: Jaarboek voor Middeleeuwse Geschiedenis, 6 (2003) 161-236.

6. Ludo Jongen & Cees Schotel, Het leven van Liedewij, de maagd van Schiedam. De Middelnederlandse tekst naar de bewaarde bronnen uitgegeven, vertaald en van commentaar voorzien, Hilversum 1994.

Credits

- My thanks to Charles Caspers, Koen Goudriaan and Ludo Jongen for their help and valuable comments on earlier drafts of The Life of Lidwina of Schiedam Written and Printed.

- The woodcuts are from two of the early editions and are courtesy of Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht. They were included in Brugman’s Latin Vita alme virginis Lijdwine, 1498 (cat.no. BMH i44) and the Middle Dutch text Tleven, 1505 (cat.no. BMH Warm pi 1259B5(3)), both editions printed by Otgier Nachtegael.

Addendum

There are four copies of Brugman’s Vita alme virginis Lijdwine printed by Otgier Nachtegael (1498) in the Netherlands: Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht, the University Library Utrecht, the Royal Library Royal Library | National Library of the Netherlands in The Hague and the Gemeentearchief Schiedam https://archief.schiedam.nl/incunabel-liduina . The copy in the Gemeentearchief Schiedam can be downloaded as ‘Incunabel Liduina’. Other examples are located in Great Britain (4), Belgium (2), France (2), Germany (3), and the USA (4). Source: Incunabula Short Title Catalogue (ISTC).

Source

© Nelly Moerman 2016, 2019

This article is protected by copyright. Reproduction of the text, in whole or in part, is permitted only on an individual basis and under the conditions of acknowledgement of source and correct citation. In case of a financial interest or the pursuit of such an interest, copying is not allowed. In case of doubt, please contact the author, who can be reached through redactie@schaatshistorie.nl.

Read more

More articles about the history of skating