Why does Lidwina of Schiedam lie on the ice in such an odd pose?

Nelly Moerman, author

Cis van Heertum, English translation

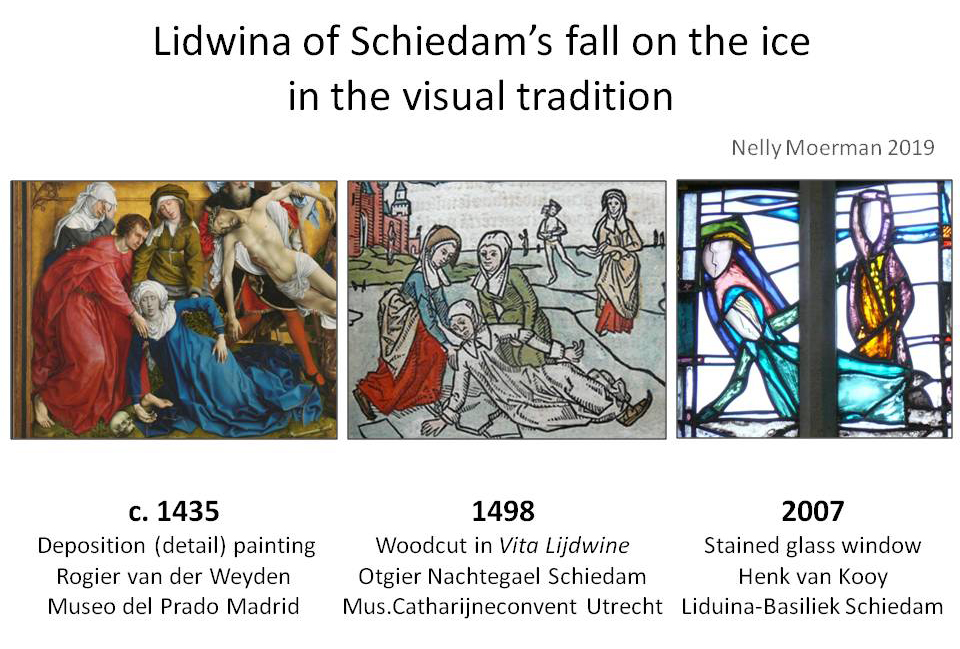

When the church wardens of Schiedam decided to print the life of Lidwina of Schiedam (1380-1433), it had to be an illustrated book. Lidwina had already been dead for over sixty years and her life had been chronicled by several authors. The text used by the church wardens was the Latin Vita alme virginis Lijdwine (The Life of the Blessed Virgin Lidwina), written by Johannes Brugman in 1456. A series of twenty woodcuts depicting events from her life was commissioned especially for the occasion. The book was printed by Otgier Nachtegael and appeared in 1498.

Woodcut

When we speak of a woodcut we commonly mean the impression. The woodblock used for making the impression, however, is also known as a woodcut. The process of making a woodcut usually starts with a drawing on paper. The design is then transferred to a woodblock whose surface has been smoothed. Next the rest of the wood is cut away, leaving a raised image which can be printed. This raised area – the woodcut – attracts the most ink, and the impression on paper from this woodblock is also known as a ‘woodcut’. The designer of the image and the woodcutter could be different persons.

Lidwina’s fall on the ice

Museum Catharijneconvent Utrecht, cat. no. BMH i44.

The best known woodcut in the series is ‘Lidwina’s fall on the ice’. (illus. 1) This woodcut became widely known and is included in numerous books on skating. It reflects the defining event of Lidwina’s life, the moment someone collides with her while she is out skating with friends. Lidwina falls on her right side on a fragment of ice and breaks a short rib. This accident is the beginning of a life of illness and misery.

The woodcut reflects the situation directly after the fall. Two friends are kneeling down by Lidwina and try to get her back on her feet. A third woman is approaching across the ice. In the background we see skating figures and on the left a city wall with an entrance gate and towers. As with the other Lidwina woodcuts, the image is executed with clear lines and simple hatching. (ref. 1)

Fractured rib? Fractured hip?

Lidwina’s odd pose and the first-aid treatment by her friends merit some attention. Anyone with some experience in first aid knows that a person with a broken right rib must not be lifted this way. The victim would cry out with pain and refuse help. The way in which Lidwina lies on the ice would rather suggest a fractured hip. But why a fractured hip?

In the woodcut showing Lidwina’s fall on the ice her face clearly shows pain and she is unable to stand. Judging from the position of the foot, her left leg is lying in an unusual, contorted position. These details point to the three classical symptoms of a bone fracture, i.e. pain, misalignment and loss of function. Unfortunately a fractured hip does not match with the story. The text clearly states that Lidwina’s right short rib was broken. Text and image do not correspond in this respect. How might this be explained?

Correspondence of form with the swooning Mary group

The helpless Lidwina and the two women assisting her are the core of the woodcut. A similar group of three is often depicted in paintings on the crucifixion. This group of three is known as the swooning Mary group. The Virgin Mary faints, is caught by John and supported by her half sister Mary of Cleophas. The group is always depicted left of the cross and has iconographic significance.

A fine example of a swooning Mary group is the Descent of Christ from the Cross by Rogier van der Weyden dating from c. 1435. (ill. 2) Note the pose of St John, his hand on Mary’s shoulder, the bent knee and the foot emerging from under his clothes. This pose is identical to that of the woman supporting Lidwina. The position of her right hand and the bent knee are the same. Her foot also emerges from under her dress, though she is wearing what is called in Dutch a ‘prikschaats’, a skate with a spike close to the toe. There is clearly a correspondence of form here. Lidwina’s pose in the woodcut matches that of the swooning Mary in the painting.

Could Rogier van der Weyden’s painting have served as a model? In theory this is possible. The painting is nowadays in Madrid, but in those days it hung in a church in Louvain. Art historians have also pointed to a possible relation with the work of Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen (c. 1472-1533).(ref. 2) This painter produced several crucifixion scenes with a similar swooning Mary group. (ill. 3) Van Oostsanen’s manner of painting is furthermore said to be distinguished by its ‘graphic character’, which would be in line with the work of a woodcutter. These are important clues, but they do not offer absolute certainty about the identity of the maker of the woodcuts.

A continuing visual tradition

It is clear by now that Lidwina and her friends were modelled after the iconographic arrangement of a swooning Mary group. Lidwina’s theatrical pose on the ice in the woodcut does not agree with the character of an active skater which she no doubt was. Throughout the centuries, however, this has become the customary representation of Lidwina. The Basilica of Saint Liduina in Schiedam for instance features a window made by the stained glass artist Henk van Kooy in 2007. (ref. 3) Lidwina’s fall on the ice is part of the window. (illus. 4) The image clearly references the woodcut. Here, too, we find a group of three, with the faces sparsely sketched in profile. Lidwina, all dressed in blue, is the central figure and is portrayed en face as she lies helpless on the ice – as in the woodcut. The position of the arms and even the headdress are identical. The two women behind Lidwina also appear to have been inspired by the other women in the woodcut. It is a fine example of how a visual tradition originating from the Middle Ages continues to carry meaning today.

References

1. Nelly Moerman, Lidwina van Schiedam nader bekeken: Houtsneden in vroege drukken, Amsterdam 2012.

2. Daantje Meuwissen, ‘A painter in black and white: the symbiotic relationship between the paintings and woodcuts of Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen’, in: Making and Marketing: Studies of the Painting Process in Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Netherlandish Workshops, Molly Faries (ed), Turnhout 2006, pp. 55-81.

3. Nelly Moerman, ‘In hout gesneden. Verbeelding en beeldtraditie in Het leven van Liduina van Schiedam’, in: Beelden van Liduina, Heilige van Schiedam, Schiedam 2015, pp. 77-88.

Credits

- The images of the woodcuts were made by the author, courtesy of Museum Catharijneconvent Utrecht. The image of the stained glass window in the Basilica of Saint Liduina was also made by the author.

- ‘The Crucifixion’ attributed to Van Oostsanen is in a private collection, courtesy of Thomas Agnew & Sons, London.

- ‘Descent of Christ from the Cross’ by Rogier van der Weyden is in the public domain.

Source

© Nelly Moerman 2018

This article is protected by copyright. Reproduction of the text, in whole or in part, is permitted only on an individual basis and under the conditions of acknowledgement of source and correct citation. In case of a financial interest or the pursuit of such an interest, copying is not allowed. In case of doubt, please contact the author, who can be reached through redactie@schaatshistorie.nl.