Rembrandt’s skating etchings and the development of visual tradition

Nelly Moerman, author

Cis van Heertum, English translation

Rembrandt (1606-1669) created a vast oeuvre in the course of his life. Expressed in figures it amounts to some 300 paintings, 2,000 drawings and more than 300 etchings. Only a few items feature skaters: one small painting, which is in Kassel (Germany), and two small etchings. The Kassel painting has been discussed in Skating in the work of Rembrandt and the difference between Rembrandt and Avercamp. This article focuses on the two small etchings. The images are available online on the websites of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the British Museum in London. This makes it possible to view every detail strongly enlarged.

Skater in perfect balance

Of the two skating etchings The Skater (fig.1) is the best known. The square print only measures 6 x 6 cm and dates from c. 1639, when Rembrandt was in his early thirties. The illustration shows a skater who has just set off and glides across the ice in perfect balance and without apparent effort. The movement in the skater’s beard indicates he is gathering speed and is skating against the wind. He is loosely holding his lower arms in front of his chest, to balance the long stick he is carrying over his right shoulder. The stick, which ends in a tooled round knob, is so long that the top end is not visible. It could be a reaping hook or an eel spear. The latter is less likely, however, since the skater is not carrying an axe or an eel buck. The man is dressed warmly against the cold and is wearing thick mittens. His headgear might be described as a beret with a fur-trimmed rim.

Left eye closed

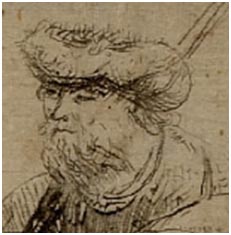

The scene breathes an almost palpable air of tranquility. The cold, the head wind, the sound of the skating irons, all these sensations are evoked by this small print. Occasionally an author hazarded another interpretation and perceived a deeper meaning in the skater’s face. While the man is gazing in the skating direction with his right eye, the left eye remains closed. (detail fig.2) It might indicate, according to this interpretation, that the left eye reflects the ‘gaze turned inwards’, while the right eye represents the ‘gaze turned outwards’. Why can’t it just be a skater who has to shut one eye against the wind that is bothering him?

Binding in front part of the skate

For skating enthusiasts another question is probably more important: What kind of skates is the man wearing? When discussing the skates in the painting in Kassel it was pointed out that Rembrandt was able to evoke something with only sparse means. Here, too, the skates are more a suggestion of skates than a faithful copy. What is obvious, however, is that the iron ends under the heel and culminates with a short neck in a point at the front. There is furthermore the obvious indication of a binding with a foremost toe piece, especially on the left foot. (detail fig.3)

The skater in the background

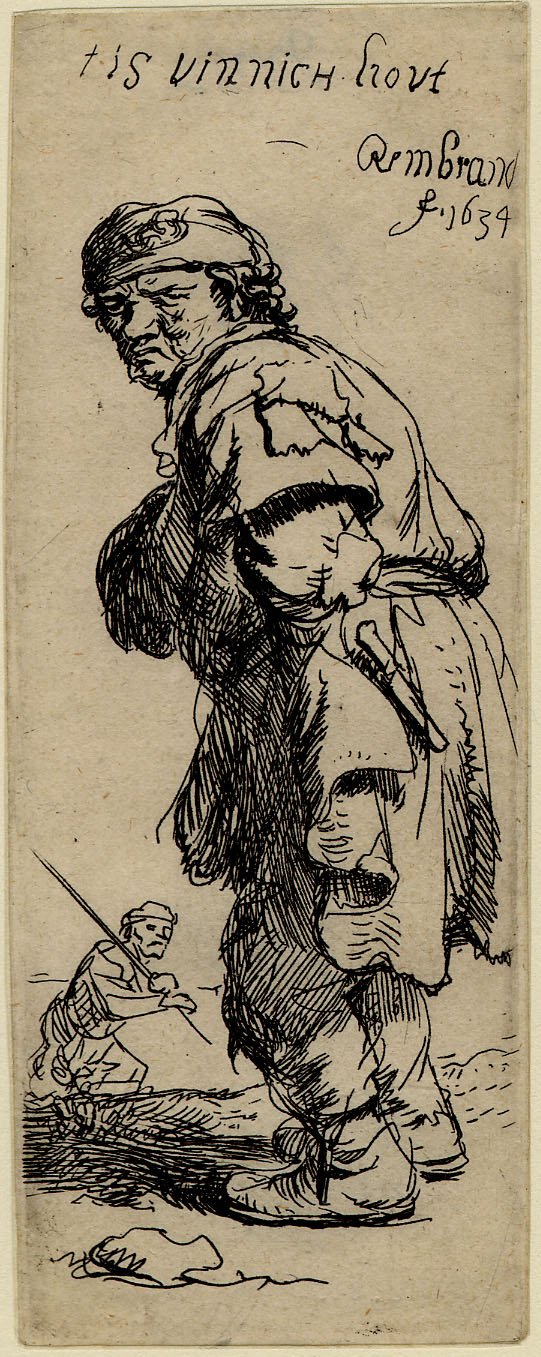

In Rembrandt’s second skating etching the skater is merely a detail in the background. The rectangular etching measures 11 x 4 cm. (fig.4) A man in tattered clothes stands hunched over and looks peevishly in the direction of the viewer. That he is cold is apparent from the text above his head: Tis vinnich kout (It’s biting cold).

The skater in the background indicates it is not just cold outside, it is freezing cold. The ditches are frozen and people are skating. (fig.6) There is a companion piece to this print showing a cheerier figure with the text: Dats niet (It’s not). (fig.5) The two are pendant etchings, the only pair to be found in Rembrandt’s oeuvre. The signing and dating feature a few unusual details. The letters ‘d’ and ‘t’ are missing in Rembrandt’s name in the print showing the jolly man and the last digit of the year is also lacking. In the print showing the peevish man only the final letter ‘t’ of Rembrandt’s name is missing. It is known that Rembrandt did not make preparatory sketches but etched directly on the plate. It looks as if he worked fast here and found he did not have enough space. The year in both prints is preceded by the italic “f.”, the abbreviation of fecit, to indicate he made the etching himself.

A design of his own

7. Es ist kalt weter (Cold weather today)

8. Das schadet nit (No it’s not)

It is very likely that the engravings made by Sebald Beham in 1542 served Rembrandt as a model. (fig.7+8) Sebald Beham (1500-1550) was a German painter and engraver who lived a century before Rembrandt. It is known that Rembrandt possessed some of this artist’s prints. The two model prints by Beham are even smaller than Rembrandt’s and measure only 4,5 x 3 cm each. These ‘weather peasants’, as they are known, are again companion pieces and also deal with the contrast between cold and warm weather. The texts are engraved in neat banderoles that end in swirling garlands. Es ist kalt weter (Cold weather today) and Das schadet nit (No it’s not) can be clearly read. Rembrandt appears to have based himself on the ‘warm weather peasant’ for his etching. His own figure with the text Dats niet (No it’s not) assumes the same relaxed posture as Beham’s peasant, with his head slightly turned and his hands loosely clasped on his back. In the cold weather print, however, Rembrandt decided on a design of his own and created a raggedly dressed figure. Rembrandt always shows compassion in his work with the plight of poor wretches, beggars and tramps. The print Tis vinnich kout was undoubtedly meant to put the message across that the cold of winter brought a lot of hardship on these unfortunates.

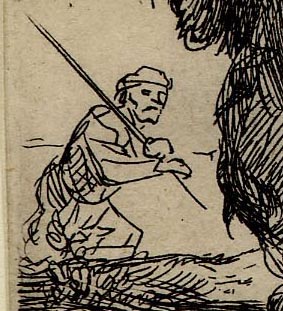

Dutch skater identified by the ice stick on his shoulder

Why can we confidently identify the man in the background in Tis vinnich kout as a skater? All we see, after all, is a man’s upper body leaning forwards. Couldn’t it be somebody at work there in the background who is about to fall over? No, it is undeniably a skater! Not only because the context suggests coldness but especially because the man has a stick across his shoulder. There are several types of sticks. A frequently depicted stick is a wooden stick with an iron hook at the end. (fig.9) This stick, called ‘IJshaak’ in Dutch, can help the skater get out of the water when he falls through the ice. A wooden stick without the hook can be used to hang things on for transportation. Although nowadays nobody skates this way, we are familiar with the image through transmission from the past. Over the years it has become part of our collective memory and we can summon it up instantly. This is how the Dutch used to skate!

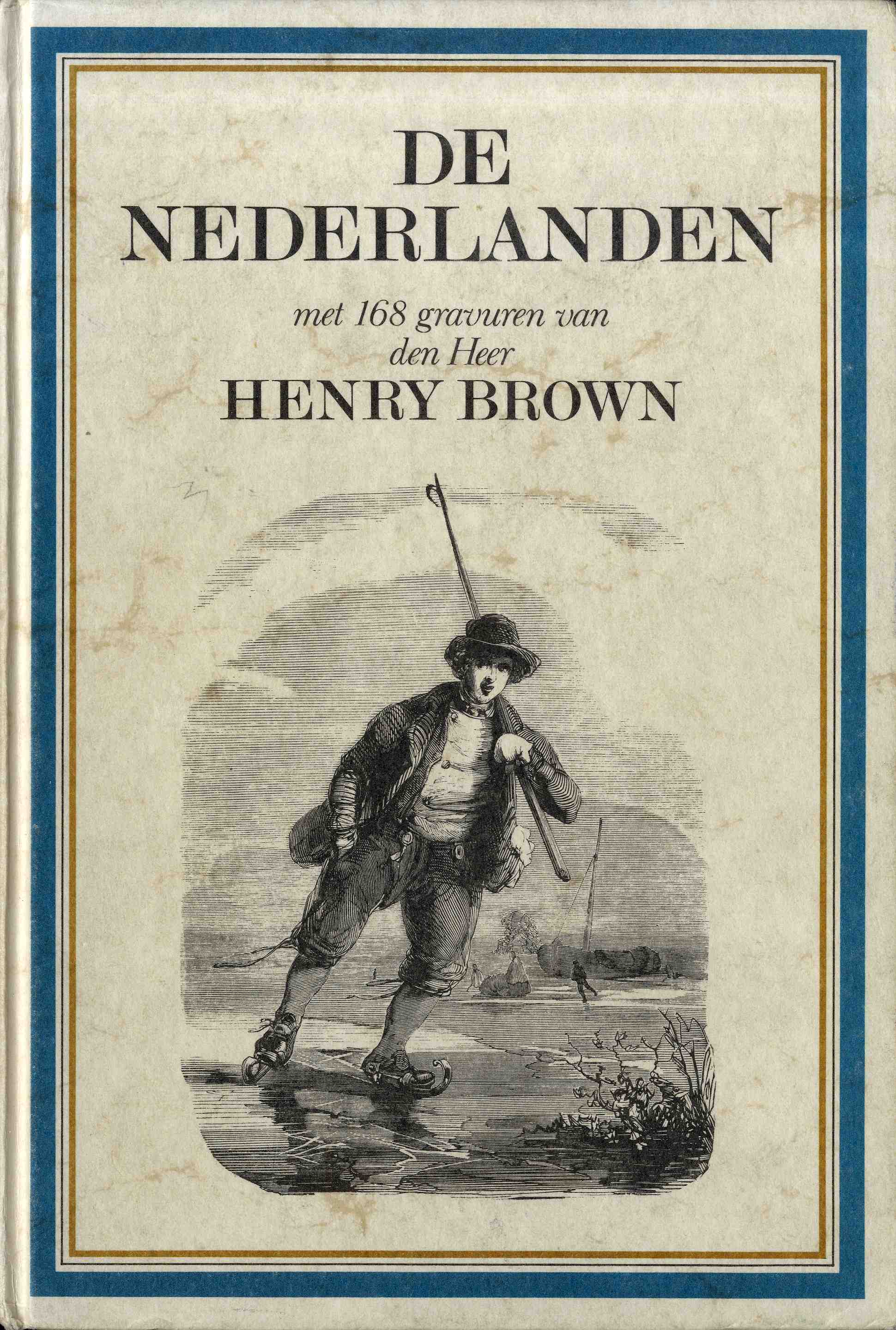

19th-century characterization of Dutch types

This was also the conviction of the 19th-century members of the Nederlandsche Maatschappij voor Schoone Kunsten (Dutch Society of Fine Arts) in The Hague. The Society decided to provide descriptions of several types of people in the Netherlands. Many of the types are now mostly forgotten, such as: Het Luthersche weesmeisje (the Lutheran orphan girl), De duivenmelker (the pigeon fancier), De hondendokter (the dog vet), De Scheveningsche vischvrouw (a fishwife from Scheveningen), De aanspreker (the announcer), etc. In all, a series of 42 ‘characters’ were produced. Naturally De Schaatsenrijder (the skater) also had a place in this series. Prominent authors like Jacob van Lennep and Nicolaas Beets were asked by the Society to provide comments to characterize each type, and artists were commissioned to portray them in drawings, which were then engraved by the printmaker Henry Brown. The result was a richly illustrated book with the promising title De Nederlanden, which was published in 1841. The 1980 reprint of this work featured the engraving of De Schaatsenrijder on the cover as an eye-catcher. (fig.9)

A remarkable similarity

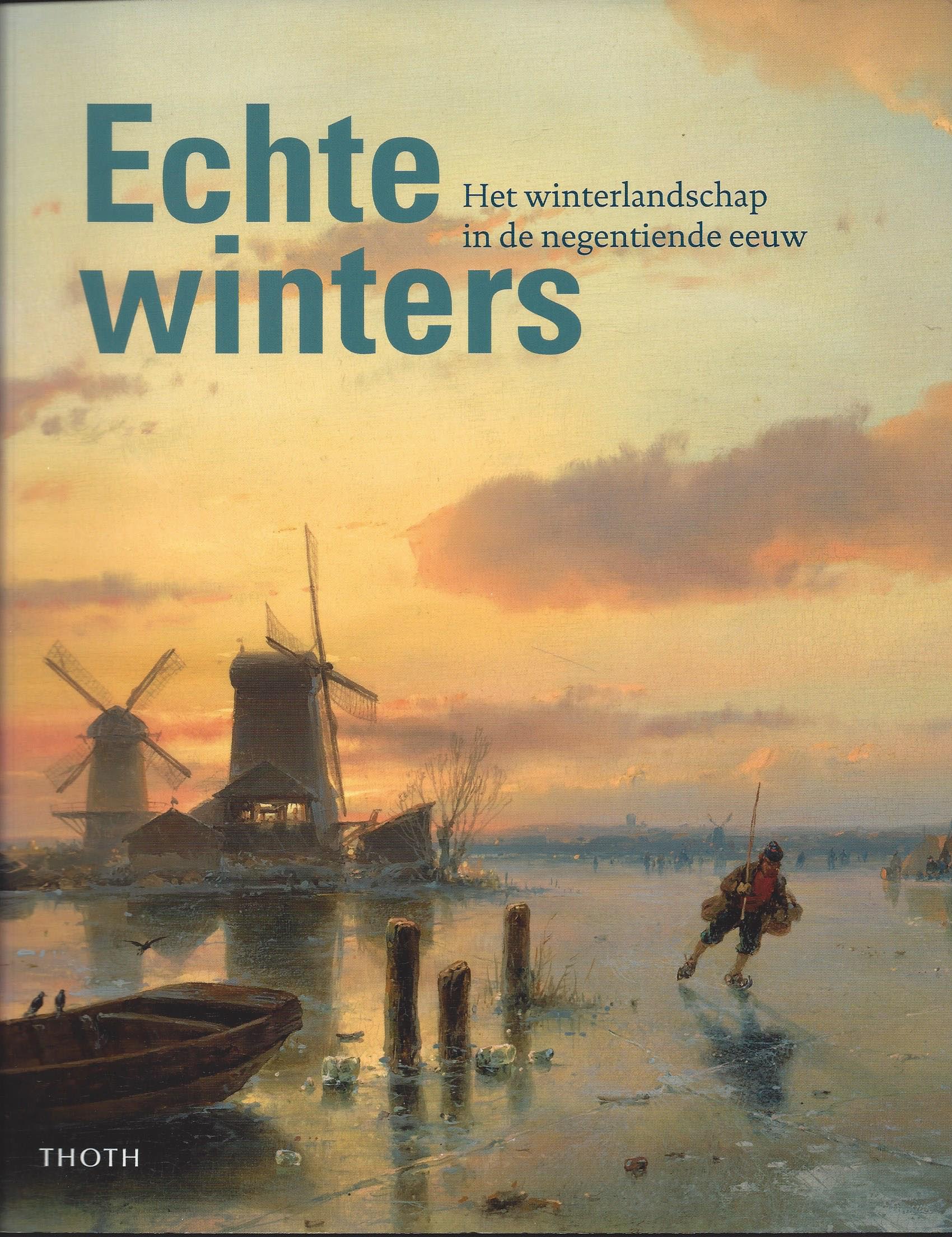

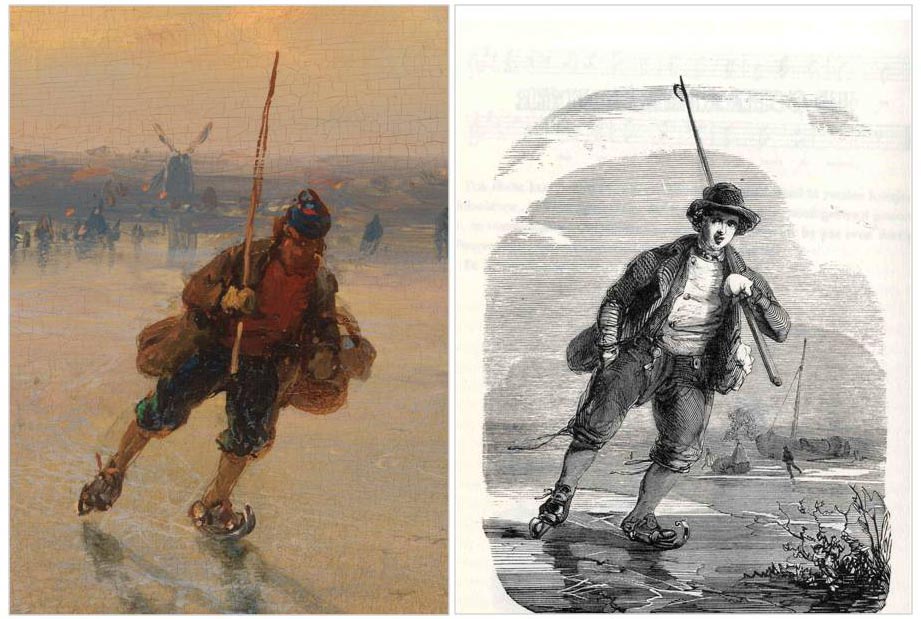

Something similar was done for the catalogue of the exhibition Echte Winters which was shown at Teylers Museum in Haarlem in the winter of 2015-2016. Here, too, a skater was chosen to serve as the cover illustration, in this case a detail from a painting by Andreas Schelfhout (1787-1870). (fig10) There are remarkable similarities between the skater featured in De Nederlanden and the one in the Echte Winters catalogue. (fig.11) Looking at the contour from the shoulders, the open coat, the trouser legs, lower legs, skates and bindings, the similarity is so strong it is almost inevitable that the same model was used. Both skaters have the characteristic stick over the shoulder. Although it is true that the shoulders are different, the open coats and the vests underneath are identical.

Cap replaced by a hat

Schelfhout is one of the few painters of winter scenes who frequently depicts a skater with an open coat. Who might have been the artist behind the drawing in De Nederlanden? Most drawings in this book were signed by the artists, but a signature is lacking in the case of De schaatsenrijder. Schelfhout’s name, however, does occur in the advertising brochure for the work, which makes it very likely that the engraving of the skater in De Nederlanden was based on a drawing by Schelfhout. Some changes were introduced, such as the stick, which is now across the other shoulder, while the headgear is also different. It is unknown why this was done and by whom. A case can be made for placing the stick across the other shoulder, it creates a more balanced image. But why was the cap replaced by a hat? It is possible that the members of the Maatschappij voor Schoone Kunsten preferred a ‘posher’ figure and so favoured a hat above a cap. It may also be the reason why the basket filled with goods in the painting has disappeared in the engraving. The typical stick was apparently not an issue. It has remained part of the iconography of the Dutch skater.

Rembrandt’s skater in the visual tradition

All this makes clear that the skater with a stick over his shoulder is part of a long-standing visual tradition. Avercamp already painted this figure in the early 17th century and many painters of the winter landscape genre continued to work in this tradition. Rembrandt, too, stands in this same visual tradition with his small etchings. What is so special about Rembrandt is that he not only studied the skating movement, he also tried to capture the individual experiences of his subjects. He combined both aspects in his Skater (De Schaatsenrijder), the small etching that was first discussed in this article. In all simplicity Rembrandt created a skater with a posture that reflects the essence of skating. It still has the power to resonate with the skaters of today.

References

1) De Nederlanden: karakterschetsen, kleederdragten, houding en voorkomen van verschillende standen. Henry Brown etchings. Nederlandsche Maatschappij voor Schoone Kunsten, 1841. Google Books; downloadable for free.

2) Echte Winters: het winterlandschap in de negentiende eeuw. Catalogue Teylers Museum, Haarlem, 2015.

Credits

Detail painting Andreas Schelfhout courtesy of Teylers Museum, Haarlem.

Catalogue numbers of etchings:

|

Artist, Title of the image |

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam |

British Museum London |

|

Rembrandt, De schaatsenrijder / Skater |

RP-P-OB-237 |

F,5.101 |

|

Rembrandt, Tis vinnich kout |

RP-P-OB-417 |

F,5.132 |

|

Rembrandt, Dats niet |

RP-P-OB-418 |

F,5.133 |

|

Sebald Beham, Es ist kalt weter |

RP-P-OB-10.897 |

Gg,4C.55 |

|

Sebald Beham, Das schadet nit |

RP-P-OB-10.898 |

Gg,4C.56 |

Source

This article is a revised version of an article that was previously published in Kouwe Drukte 2016; no. 56, pp. 30-34. [ISSN 1572-4476]

© Nelly Moerman 2016, 2019

This article is protected by copyright. Reproduction of the text, in whole or in part, is permitted only on an individual basis and under the conditions of acknowledgement of source and correct citation. In case of a financial interest or the pursuit of such an interest, copying is not allowed. In case of doubt, please contact the author, who can be reached through redactie@schaatshistorie.nl.