Salomon van Ruysdael and Skaters on the Ice near Alkmaar

Nelly Moerman, author

Cis van Heertum, English translation

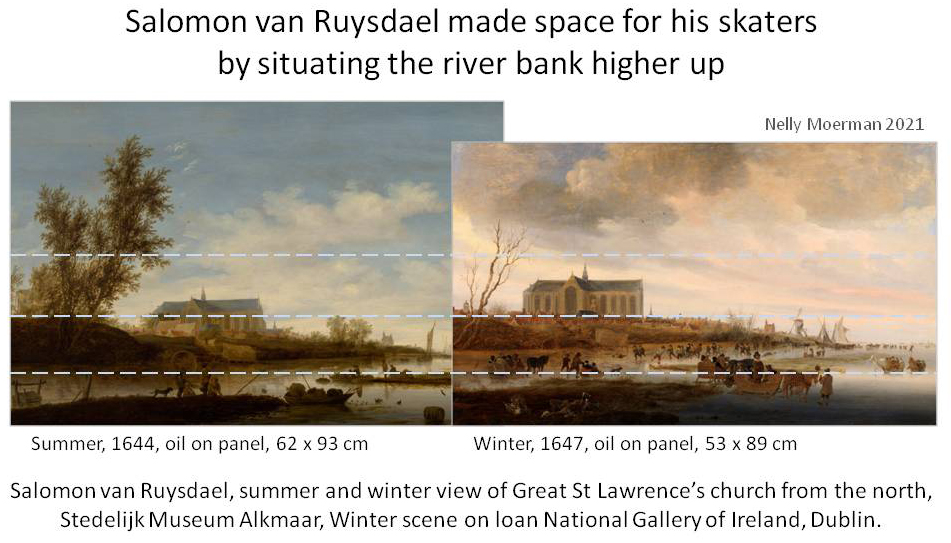

To mark the 500th anniversary of the Great St Lawrence’s Church in Alkmaar in 2018, an exhibition was organized at the Stedelijk Museum in that city entitled Ruysdael en Saenredam in Alkmaar: Meesterwerken van de Grote Kerk. (ref.1) The exhibition also featured works by several other artists. Two paintings by Salomon van Ruysdael (1600/03-1670), showing the church from the same northerly direction in summer and in winter, caught the eye. The Stedelijk Museum had been able to acquire the summer view (fig.1) the year before, the winter view (fig.2) was on loan from the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin. As this painting was subsequently given on long-term loan, both paintings can still be admired at Alkmaar. Ruysdael’s summer and winter views now hang side by side at the Stedelijk Museum as pendants.

Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar.

Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar (on loan National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin).

Pink Glow Adding to the Sense of Cold

In the summer scene, the church is depicted as a lofty building on the horizon, placed slightly off-centre. (fig.1) On the left the view is bordered by a clump of trees. A high-banked river winds its way across the entire width of the painting to end in open water on the right. The winter scene could be described in similar terms, only now the trees on the left are completely bare and the river bank has lost most of its green. The summer piece dates from 1644, the winter piece was painted three years later, in 1647. The summer scene is extraordinarily balanced in composition and colour. A warm summery light settles on the church from the left, reflecting on the roofs of the adjacent houses in hues of ochre. In the winter scene, the sun is not to be seen, the sky is overcast. A soft pink glow filters through a thin band of clouds, adding to the sense of a wintry cold. It’s crowded on the ice, with the hustle and bustle of activities serving to heighten the painting’s charm.

A Higher Horizon

If we compare the position of the horizon in the two paintings, it is obvious that Salomon van Ruysdael painted the horizon a lot higher in the winter piece than in the summer one.

In doing so, he created space to depict the fun on the ice. (fig.3) The skaters all appear to be following the same route, which leads them past the river bank to an expanse of ice stretching to the horizon. Some skaters are moving towards the open space, many more are already on their way back. (fig.4) It is mainly men who take this route, their hands crossed behind their backs or their arms crossed in front of their chest. There are also a few women to be noticed, taking the same route together with a male companion. The white of the women’s wraps and the men’s white collars and cuffs provide lively accents in the wintery scene. The painting is so full of life it almost makes you want to put on your skates and join in.

Eye-catcher

Not only skaters are enjoying themselves on the ice, there are also many horse-drawn sleighs filled with passengers to be seen. The sleigh in the foreground, which is seen in side-view, is a real eye-catcher. (fig.5) There is space for four passengers in the sleigh itself, while the driver has his own seat at the back. The splendidly adorned horse is harnessed and ready to pull its weight. But the sleigh has not left yet and a man is standing proudly upright and gazing at us as if he wants to make something clear. Perhaps he was the owner of the sleigh, or commissioned the painting.

In the Shadow of his Nephew Jacob

Who was Salomon van Ruysdael? He was born in Naarden (1600/03) and moved to Haarlem, where he enrolled in the city’s painters’ guild, the Sint-Lucas Gilde, in 1623. He lived in Haarlem all his life and was buried there in Saint Bavo’s church in 1670. There were more painters in the family. Especially his nephew Jacob van Ruisdael, who was twenty years his junior and who wrote his name with an ‘i’ instead of a ‘y’, was famous already in his own time. In fact, during his entire career Salomon worked in the shadow of his far better known and universally renowned nephew. It is thanks to the Dutch art dealer Jacques Goudstikker that Salomon’s paintings received greater appreciation. In 1936 Goudstikker organized a retrospective of his work, for which he managed to bring together sixty paintings. (ref.2) He described Salomon van Ruysdael’s paintings with an enthusiasm bordering on the lyrical, praising the ‘cheerful merriment reflected in his transparent and open, straightforward paintings’ (blijde feestelijkheid, die zijn klare, open, eerlijke schilderijen uitstralen). According to him, all of Salomon’s paintings breathed peace and quiet. He also believed Salomon must have been a happy person to be able to paint the way he did.

Beethoven’s First

Today also, it looks as if that special feature of Salomon’s paintings is still recognized and appreciated. There are several videos on YouTube that combine his paintings with text or music. One of them is a video in which Beethoven’s First Symphony is accompanied by images of 83 paintings by Salomon van Ruysdael. Unfortunately for skating enthusiasts, only five ice scenes have been included, whereas Salomon must have painted over 25 of them. (ref.3) The colours on YouTube are not always very nice, but it is obvious how music and image can enhance each other. For the Beethoven video search YouTube: Salomon Ruysdael Beethoven

Rigid Figures

Salomon van Ruysdael is credited with a large oeuvre. The German American art historian Wolfgang Stechow came to more than 600 works in his survey. (ref.3) Salomon already painted a few ice scenes early on in his career. The first one dates from 1627 and is part of the collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. (fig.6) Its title is Winterlandschap aan het water (Winter Landscape on the Waterside). There are hardly any skaters to be seen, the winter season is evoked by the activities taking place on the river bank. On the left a few men are busy shifting hay near a cart. Nearby people are warming themselves at a fire. More to the right a number of fairly rigid figures have been grouped together near three sledges in a rather contrived composition. Three couples are standing around them, the couple on the left is painted with their backs to the viewer.

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Gemäldegalerie.

An Eye for Detail

The first ice scene dates from 1627, the painting with the expanse of frozen water near Alkmaar was painted in 1647, a time span of twenty years. The great difference between these two paintings illustrates Salomon van Ruysdael’s artistic growth. The horizontal arrangement of the first painting is rather flat, more like the illustration of a theatrical scene. There is much greater depth in the painting he made in 1647. Here, Ruysdael has painted an expanse of ice stretching away into the distance, with people busy on the ice in an absolutely natural arrangement. That he was gifted with an eye for detail from the start is clear from the way he painted the middle of the three standing couples in the early painting. The male figure carries his left arm in a sling, (afb.7) a rare detail in paintings. Perhaps he had suffered an accident, having stumbled on the slippery ice or fallen while skating? We do not know and we will never find out. What we do know is that thanks to a minor detail like a sling, Ruysdael managed to imbue this minor figure with individuality, making the image as a whole come to life. This is Salomon van Ruysdael’s great achievement.

References

1. Christi M. Klinkert, Ruysdael & Saenredam in Alkmaar: Meesterwerken van de Grote Kerk, Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar 2018.

2. Catalogus der tentoonstelling van werken door Salomon van Ruysdael in den kunsthandel J. Goudstikker, Amsterdam, January-February 1936.

3. Wolfgang Stechow, Salomon van Ruysdael: eine Einführung in seine Kunst, 2nd ed., Berlin 1975.

This article is a revised version of an article published in Kouwe Drukte (2018) no. 62, pp. 16-19 [ISSN 1572-4476]

Credits

Photograph of the summer piece showing the Grote Kerk in Alkmaar by Margareta Svensson. The winter piece depicting the Grote Kerk in Alkmaar is on loan at the Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar, courtesy of The National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin. The photograph of the painting showing a winter landscape on the waterside (1627) is ©Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

My thanks to the Stedelijk Museum in Alkmaar and the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna for their permission to reproduce the images.

© Nelly Moerman 2021

This article is protected by copyright. Reproduction of the text, in whole or in part, is permitted only on an individual basis and under the conditions of acknowledgement of source and correct citation. In case of financial interest or the pursuit of such an interest, copying is not allowed. In case of doubt, please contact the author.