Bone skates as forerunners of the wooden skate

Author

Author Wiebe Blauw, 2001

Translation Cheryl Richardson, 2018

Bone skates as forerunners of the wooden skate

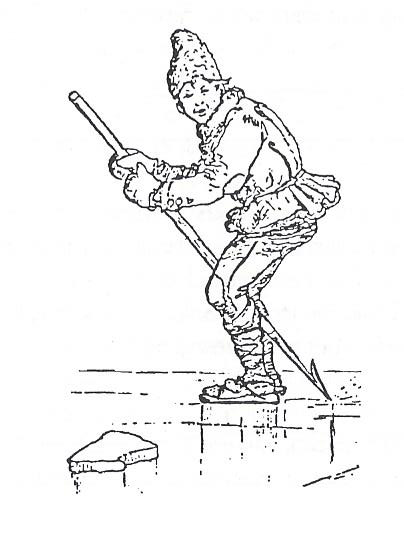

The forerunner of the wooden skate is the bone runner or bone skate. Bone runners are planed and flattened bovine or horse bones that tie under the feet and on which one can slide. To attach leather straps or strings to these runners, holes were drilled through the bone. Bone runners have been found in all the wetlands in the Netherlands. They often differ in form and degree of processing. The problem with bones on the ice is that ‘edges’ cannot be fashioned. So in order to move forward, skaters needed to make use of one or two prods that were pushed backwards between the legs. Moving forward on bone skates actually has more in common with cross-country skiing than with skates. Nevertheless, bone runners in the Netherlands must be regarded as the precursor of the skate, because it is the first time we see standing and moving on ice.

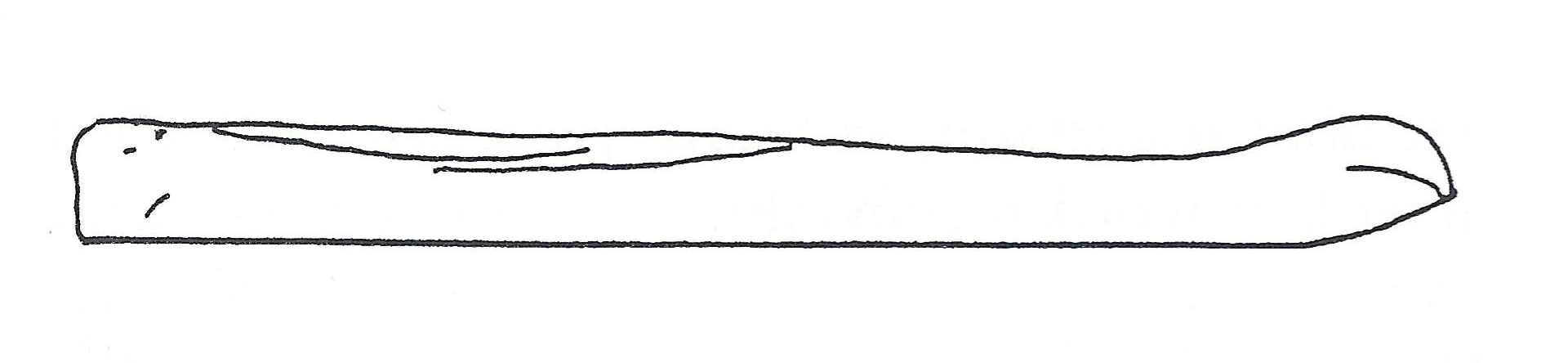

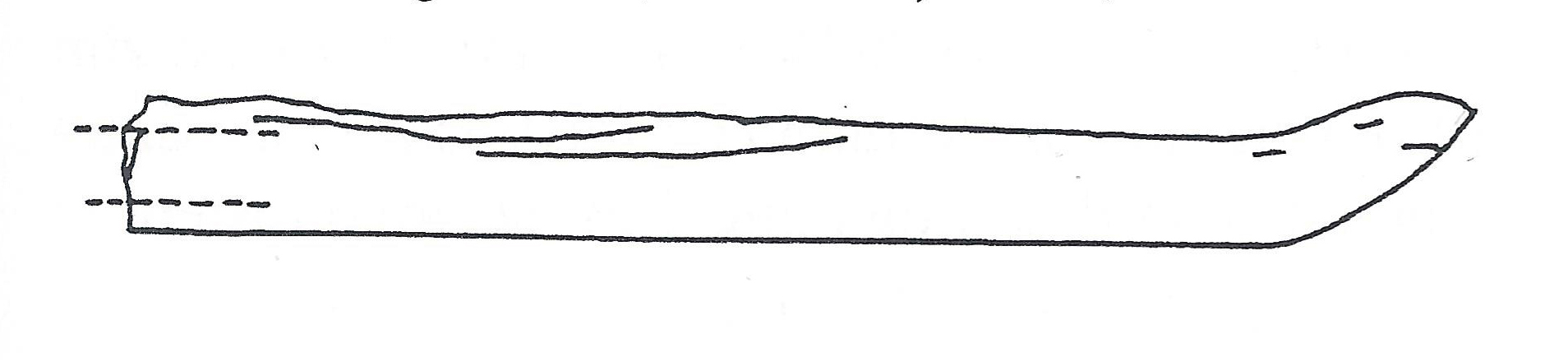

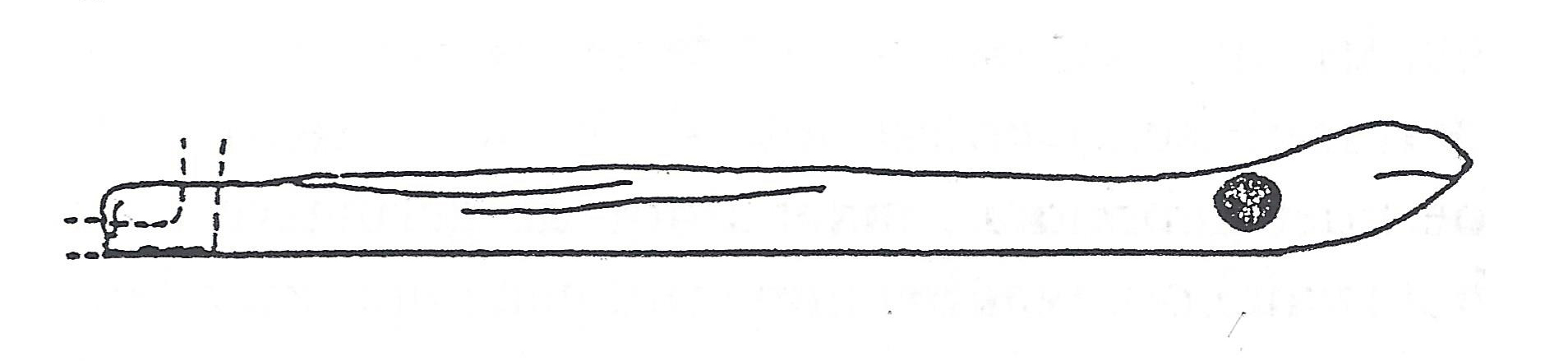

Length: 22cm

Collection Frits Locher

Knowledge about gliding is the result of archaeological research in which different finds are compared. In the last century, archaeological researchers still differed about the nature of the processed bovine bones they found. In December 1834, Mr. C.A. Rethaan Macaré for the Zeeland Society of Sciences stated that the bones that had been found between 1810 and 1830 and in 1834 in a mound near Serooskerke had been used for skating. He gained little support for this view. Twelve years later, in 1846, Mr. F.J.J. van Eysing of a company of the Friesch Genootschap in Leeuwarden, thought that a processed cow shank from the mound of Irnsum could be the prototype of the skate. His insight was also met with resistance. It was not until the 1850s, when both ideas were connected, that bones in the Middle Ages were recognized as a method for humans to move across the ice. In 1858 five leg-bone skates were shown at the Exhibition of Antiquities in Arti and Amicitia in Amsterdam so that a larger audience could also learn about it.

Partly because of the growing interest in archaeological research in recent decades and the increased possibilities for archaeological research by the construction of roads, sand excavations and building excavations, a large number of bone runners have emerged. They can be dated fairly accurately on the basis of secondary findings.

Bone runners were used in the Netherlands in the Middle-Roman period, starting from around 200. Outside the Netherlands they were used in the late Bronze Age, between 1200 and 600 BC (Hungary, Thuringia, Switzerland, Bosnia). From the Iron Age bone runners were found between the late 2nd and early 4th centuries in Thuringia, Frankfurt and Austria. In the Scandinavian countries, they were found from the 5th and early 6th centuries- the migration period and the Viking Age. In the Slavic period (circa 600 to 900) bone runners occurred in Saxony and Poland, while finds from Russia dated from 1000 to 1200. In England, animals were also used to move or entertain on ice. Fitzstephen, the secretary of the well-known archbishop Thomas Becket, reported about 1180 large groups of people gliding on the frozen Moorfields north of London and even of jousting on bone runners.

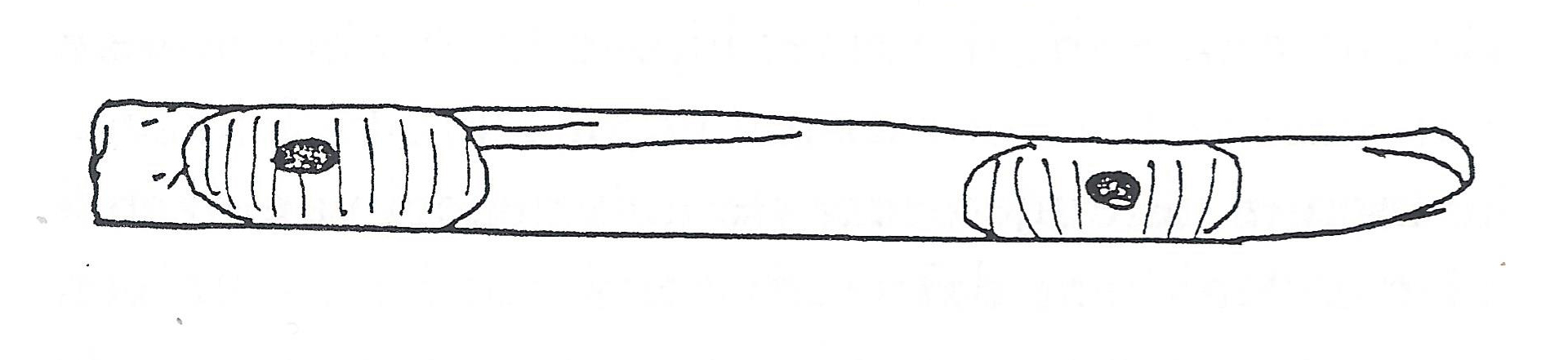

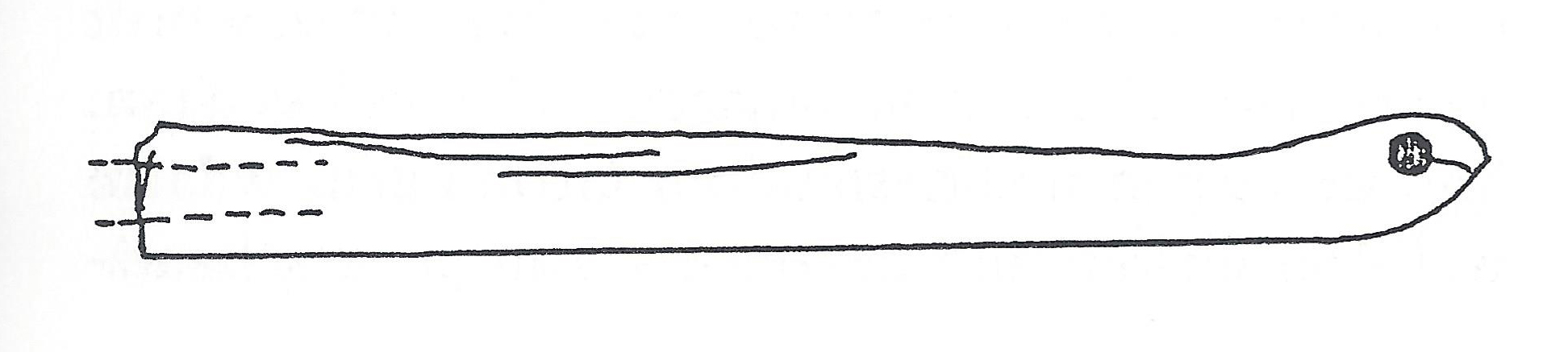

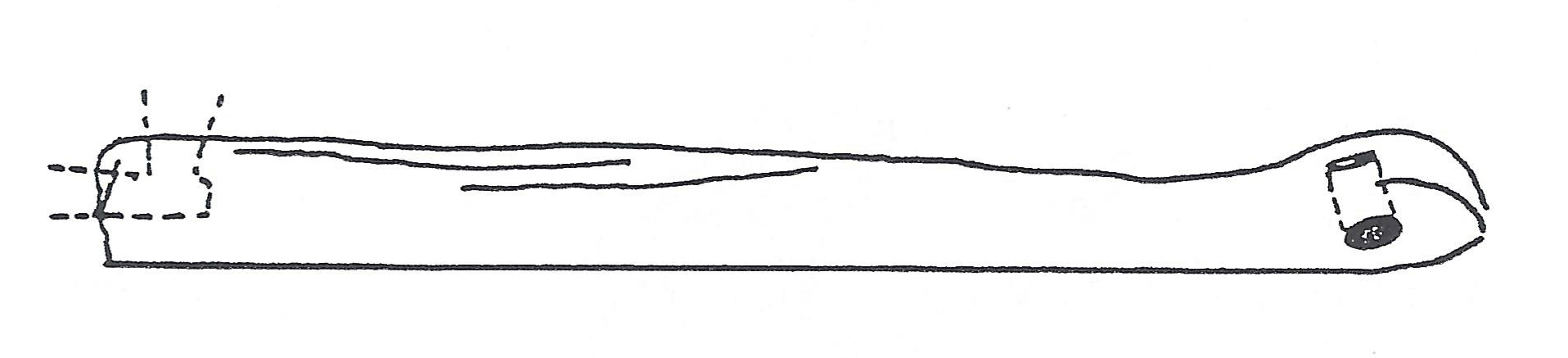

Length: 22cm

Collection Frits Locher

Bone runners were used until the last century. The Swedish scholar, diplomat and writer Olaus Magnus had the first map of Scandinavia been made in Venice in 1539. This map shows two people on bone skates (or wooden runners?) in the Gulf of Finland. In 1555 He spoke of skaters who rode both on wooden skates and on bone runners. Distance races on ice were even organized in which prizes could be won.

Various sources from the 18th and 19th century report the use of cow and oxen ribs. Not only in rural Friesland, but also in Amsterdam, cow ribs were used, especially by children, to become familiar with the ice or by people who could not afford to purchase wooden skates. In Denmark, the learned Finn Magnusen and in Westfalen the writer Vieth described the use of cow ribs by the poor and by children. The question now arises, why did a heated discussion arise about excavated bone runners when they were still being used in those days? The answer is twofold. In the first place, the bones found were metatarsal bones- no ribs- and the former were not recognized as sliding objects. In the second place, metatarsal skates did not occur in the skating culture of well-to-do and well-educated men.

Dutch Bone runners

Bone runners found in the Netherlands can be distinguished as either horse or bovine bone. Occasionally red deer bones are found (e.g. Amsterdam). It is possible that bones from other animal species have been used abroad. For example, the Rijks Japansch Museum of Von Siebold in Leiden (previously, the Ethnographic Museum and now, the National Museum of Ethnology) once owned a bone runner made of walrus originating in Siberia. In 1908, it was given as a present by Van Bemmelen to Ubel Wierda, the inventor of the multiplex skate. It is assumed that in the Netherlands wooden boards were also used to slide along. Finds of such boards are not there because isolated pieces of board would be very difficult to identify as having been used as runners. In China, in the 19th century corn stalks were placed under the foot to glide over the ice.

Among the horse and bovine bones used in the Netherlands as bone runners are three types of bones: the metatarsus, the metacarpus and the radius. Only once was a rib (costa) used. Their length varies from about 20 to 33 cm. Bone runners were used to skate but were also placed under sleds. We restrict ourselves here to the bone runners as skates. In 1976 H.W. Jacobi inventoried all the bone runners present in the Rijksmuseum voor Oudheden and the Groninger Museum voor Stad en Lande. He came to the following conclusions. About two-thirds of the bone runners came from horse and a third from cow. Approximately 45% are metatarsal bone, nearly 40%, metacarpal bone and over 15%, radius. Research from the National Office for Archaeological Soil Research in Amersfoort shows that bone runners from horses are mainly found in agricultural settlements while bone runners from cows are found more in areas with urban development. This fact corresponds to the degree of urbanization of the Carolingian period, in which there is hardly any question of urban development. The radius is considerably less common than the middle arm and middle leg. The explanation for this is that the radius is rather strongly bent and therefore requires more pre-treatment.

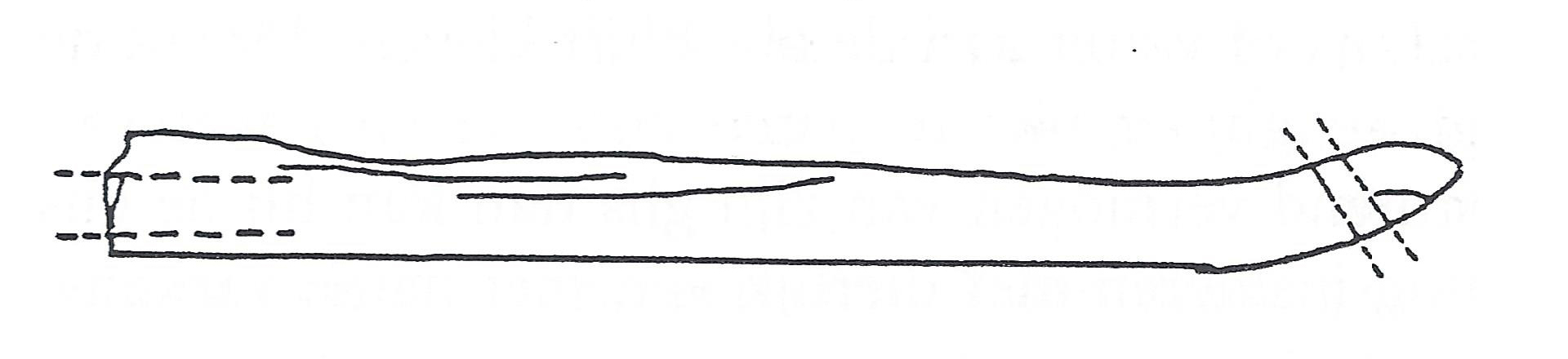

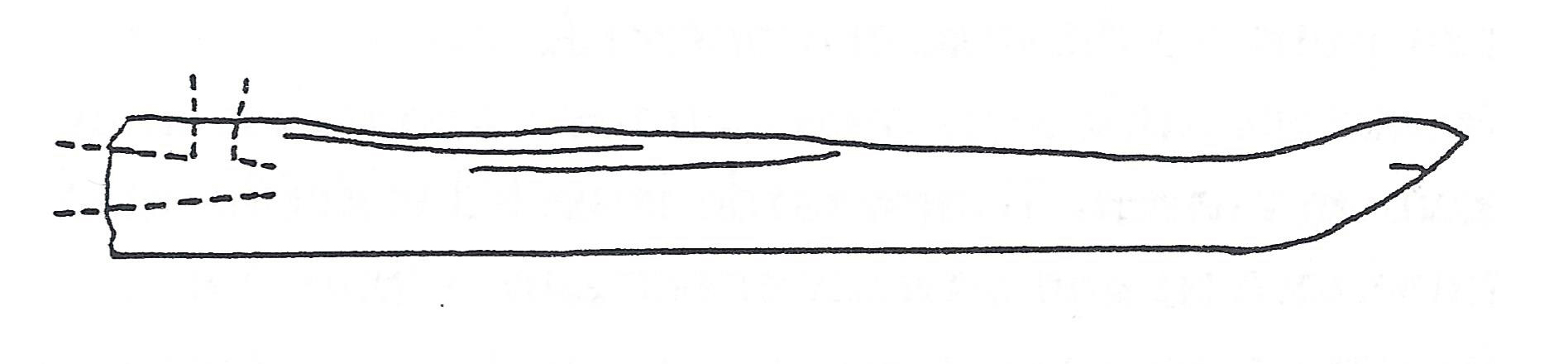

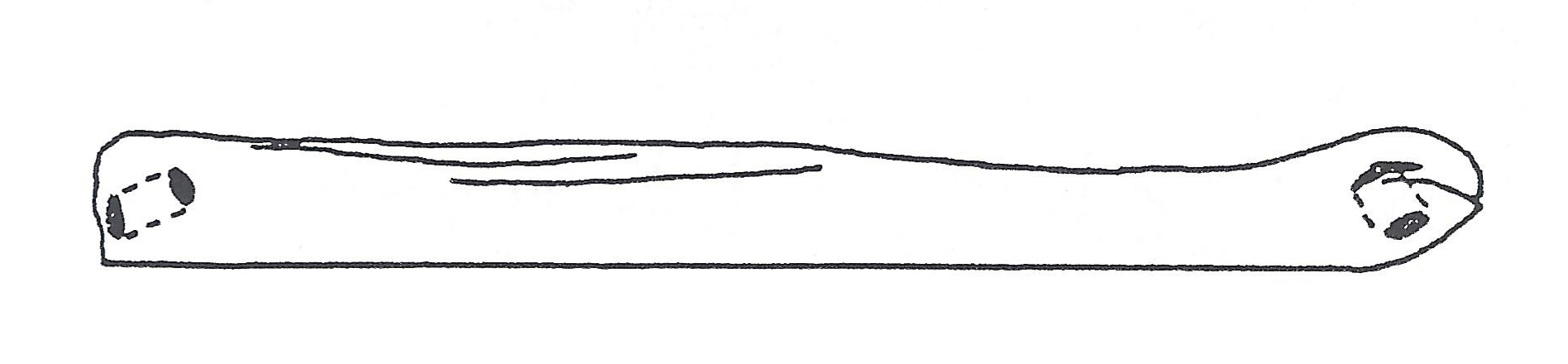

Bone skates can be recognized by the processing they have undergone. The metapodia of horses and cattle have a triangular shape in cross section. The ends of the bone show thickenings at the location where the bones hinge in the ankle or knee joint. There are essentially four operations:

- the flat part of the bone, which forms the sliding surface, is smoothed in the longitudinal direction. The thickenings at the ends are removed with a knife or an axe.

- the foot is placed on the narrower top of the bone. At the heel the thickening is removed, while at the toe only a part of the thickening is cut away or cut. The latter is important to give the foot support on the remaining raised edge.

- usually at the front, the bottom part of the bone is removed so that the sliding surface from the front rises slightly to be able to glide over unevenness on the ice. Sometimes the front is shaped into a point.

- holes are drilled through the bone to pull the straps through, which are then pulled and tied over the foot. The holes are usually drawn sideways and horizontally through the bone. Vertically pierced gliders were used to place them under sleds. The holes occur both at the heel and at the toes. Also, sometimes holes are made in the back of the bone, in which a wooden pin is struck that helps when fastening the straps. The holes vary from 3 to 8 mm in diameter.

Not all of these operations are necessarily applied. However, it is necessary that the sliding surface be smoothed. Approximately one-third of the bone runners examined by Jacobi do not have bores in them.

Types of Bone runners

Based on the refinements that have been made to bone bone runners, Jacobi created the following eleven bone runner types:

Type 1

59 of the 180 artifacts examined

No penetrations. The upper parts on the foot side are flattened and the front (the distal epiphyse) slopes. These bone skates are made to be stood on unattached, without using ropes or straps.

No penetrations. The upper parts on the foot side are flattened and the front (the distal epiphyse) slopes. These bone skates are made to be stood on unattached, without using ropes or straps.

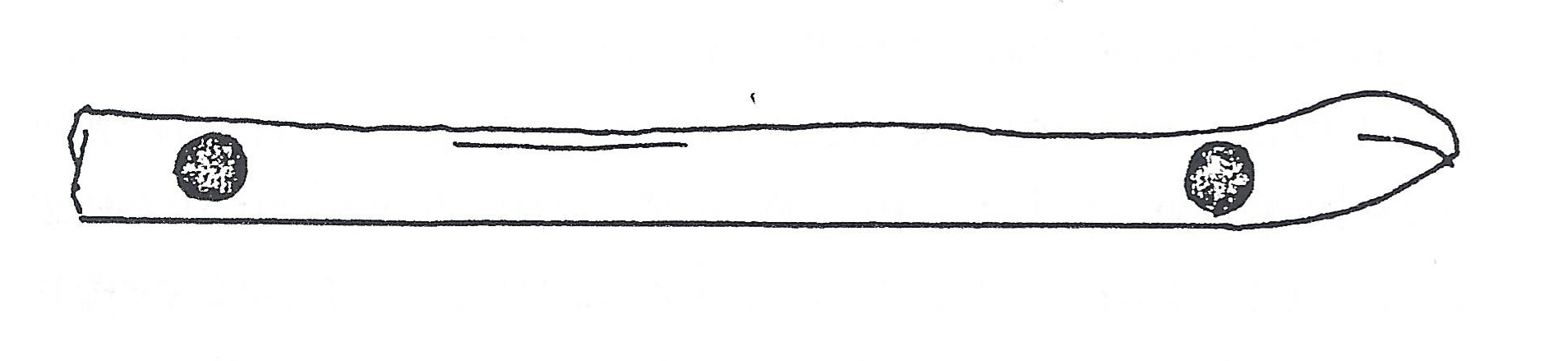

Type 2

30 of the 180 artifacts examined

Two transverse perforations, one at the height of the toes and one at the height of the heel. A corner has been chopped or cut from the bone around the holes. The holes are round or almost round, so that a string can be pulled through to attach the foot. Occasionally the hole is oval, so a belt can be used.

Two transverse perforations, one at the height of the toes and one at the height of the heel. A corner has been chopped or cut from the bone around the holes. The holes are round or almost round, so that a string can be pulled through to attach the foot. Occasionally the hole is oval, so a belt can be used.

Type 3

19 out of 180 artifacts examined

Two round cross-holes of 6 to 8 mm in diameter at the level of the toes and the heel. The holes are drilled and suitable for the use of strings.

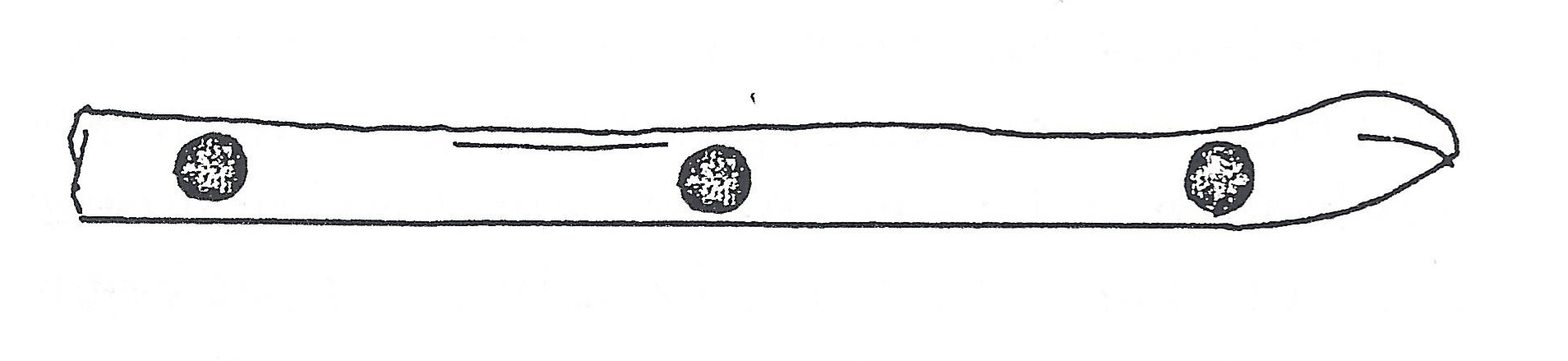

Type 3a

1 of 180 artifacts examined

Three rounded holes at the level of the toes, the foot cavity and the heel.

Type 4

19 out of 180 artifacts examined

One bore in the back of the bone (the proximal articular surface). A stick is inserted into the hole. A rope is tied to the baton, which is then tied around the ankle and attached the bone to the foot. In one case the stick was preserved and determined to be ash wood (Westerwijtwerd).

One bore in the back of the bone (the proximal articular surface). A stick is inserted into the hole. A rope is tied to the baton, which is then tied around the ankle and attached the bone to the foot. In one case the stick was preserved and determined to be ash wood (Westerwijtwerd).

Type 5

13 out of 180 artifacts examined

A bore at the back to insert a stick and a transverse hole at the toe. The fastening rope can now be laid crosswise over the foot and attached.

Type 6

3 out of 180 artifacts examined

A bore at the back and one to three slanting holes at the toes. A good cross connection is also possible with this type.

Type 6a

1 of 180 artifacts examined

In addition to the penetrations of type 6, this bone runner has a perforation at the level of the foot cavity.

Type 7

6 out of 180 artifacts examined

A bore at the rear. A connection hole to the bore is then made from the top. This would allow the rope to be tied to the bone without using a stick. Jacobi proposes that the rope can be left in place allowing the wearer to carry the pair by the rope.

Type 8

5 out of 180 artifacts examined

This bone runner has the same 'perpendicular' bore as with type 7 and also a transverse hole at the toe. In this way the bone runner can be firmly attached to the foot.

Type 9

3 out of 180 artifacts examined

This bone runner has the same 'perpendicular' bore as with the types 7 and 8, but also two oblique bore holes at the toe, so this type can also be firmly fixed to the foot.

Type 10

1 of 180 artifacts examined

This bone runner from Zeeland has two oblique penetrations at the heel and two oblique penetrations at the toe. This type also makes it possible to attach the bone runner firmly to the foot.

Finally, Jacobi mentions an eleventh type that is characterized by only oblique penetrations with a larger diameter, namely 10 to 15 mm. These bone runners were used to attach under sleds.

Bone runner Uses

By using bone runners on the ice, the bottom is further ground by wear. Since bone contains a lot of fat, ice and water don't usually stick to it. If the skater is not satisfied with the water-repellent ability of his bone runners, he can rub the bone with animal fat, in particular pork fat.

The ice prods used consist of a wooden stick with a point that goes into the ice. The tip must be made of a hard material, otherwise the tip would wear out too quickly. Initially, a piece of bone was put on the end of the stick. This piece of bone was also adapted. A hole was made in which the stick was inserted. Then the end of the bone was chopped or cut in the shape of a tip. Later an iron point was mounted on the stick.

One could probably cover long distances on bone runners. However, the ice must be smooth, hard and free of snow. In 1555, Olaus Magnus describes competitions on bone runners in journeys of 5 to 8 kilometers.

Bone runners were used until the 19th century; after that, only by people who could not afford the purchase of a pair of skates or by children who became familiar with the ice in this way.

In addition to gliding, wooden slats were also bound under the foot, but due to the lesser hardness of wood, the gliding capacity was limited. On the other hand, the wood could be processed more easily than bone and wood was always in stock.

Moving over ice with either bone or wood bone runners cannot really be termed, skating. This change took place when a narrow strip of iron was placed under the wood.

Source

The article 'Glissen' (Bone skates) is written by Wiebe Blauw, member of De Poolster.

It has previously appeared in his book 'Van Glis tot Klapschaats' (2001)

Add information or photos?

Do you have additions and / or changes to the information provided on this page? Or maybe you have photos or other imagery on this subject? Then use our comment form to send us your information. We would like to hear from you!

Press the button Informatie toesturen, see below.