Period 1750-1800

Overview

Thanks to the 'kavaljerer' from 1674 and court official Johan Ekeblad (see previous chapter) we know that skating was a popular activity with the Swedish upper-classes. In the second half of the 18th century, the number of mentions increased throughout Scandinavia.

Bron: Wikipedia

Norway

Jacob Aall (born 1773), who as owner of Næs Jernverk would become one of Norway's greatest steel barons, was forbidden the passtime of skating in his youth. He writes in Erindringer 1780-1800 that once in a while his father let the servants ‘skride’ on Vallemyrene, if it was frozen over late in the autumn. ‘He had a great time when they tumbled over each other on the slippery ice. However, we were never allowed to go ice skating ourselves. A number of events with unhappy outcomes had frightened my parents.'1

Aall's descendants supplied skating steel to L.H. Hagen from Kristiania in the mid-19th century, as we will see in a later chapter.

At the end of the 18th century, according to Urdahl, a Dutch type of skate was used in the western coastal region of Norway, an influence he explains from the lively shipping in that area.2 From an unspecified source he quotes a touching story about a young lady of respected descent. Together with her secret lover she sets out on her Dutch skates for a trip on the sea ice of a fjord ten kilometers wide and no less than fifty fathoms deep.3 Love makes blind, whether it is for the ice or the sweetheart ...

These Dutch skates that Urdahl describes might well have been German-made.

Imports from Germany

From the Factura-Büchern 1780-84 of shipping house Engelbert Luckhaus from Büchel (near Remscheid in the Bergische Land, Germany) it appears that in those years there was some limited export of ice skates to Christiania (present-day Oslo) in Norway. Like other small hardware, the skates were shipped in barrels via Hamburg.4 See further at Evolution in type of skates 1750-1800.

Bron: himfa.de

Denmark

In Denmark, Klopstock, who wrote several skating poems, presents himself as a champion of ice sports. Between 1750 and 1770, the German bard, who lived in Lyngby, north of Copenhagen, in winter hunted all the places where he could go on his long Frisian skates and with the dedication of a missionary he tried to convert his elitist Danish friends to it.5 Apparently they used another type of skate, or did not skate at all.

Sweden

In the diary of Carl Daniel Burén, owner of an iron smelter, who between 1780 and 1812 wrote stories about people close to him, he mentions how on an autumn day, not long after it had frozen, the nimble captain Fröberg from Småland crossed a lake on ice skates and in a red coat, to visit the workers on his estate at the other side. Before he went back, he said "Look how fast I will be skating back." In the middle of the lake he went through and spread his arms to save his life. However, he was ripped down by his own weight and his head was cut off by the sharp edge of the ice, as it were.

Burén also explains how quickly conditions on the vast Lake Sommen could change under the influence of the sun in early spring. A whole group of unsuspecting churchgoers, who went back home with horse and sled, might have found a certain death if a farmer's son from Stjärnsand had not skated out in front of them and discovered the treacherous hole, which had not been there at all in the morning.6

Anders Mårtensson (born 1777) from Bergsviken in the province of Jämtland (Sweden) escaped death at a young age. He had once fallen through the ice, but luckily managed to get out alive. However, he got so frightened that he swung his skates in the hole and decided never to put them on again. He never changed his mind afterwards. In fact, years later - Mårtensson had become an MP - he also forbade his sons from getting engaged in this dangerous passtime.7

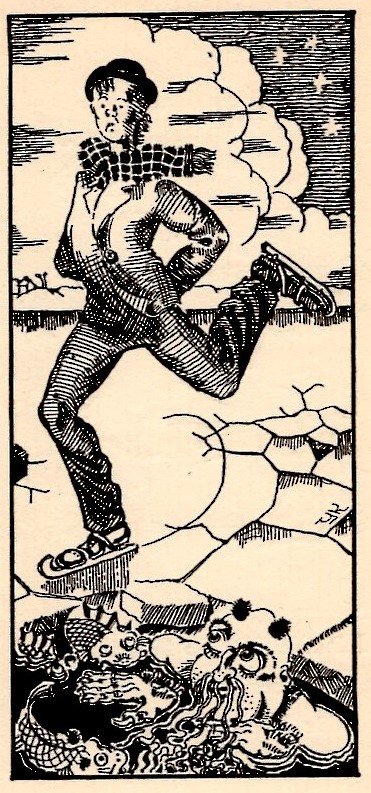

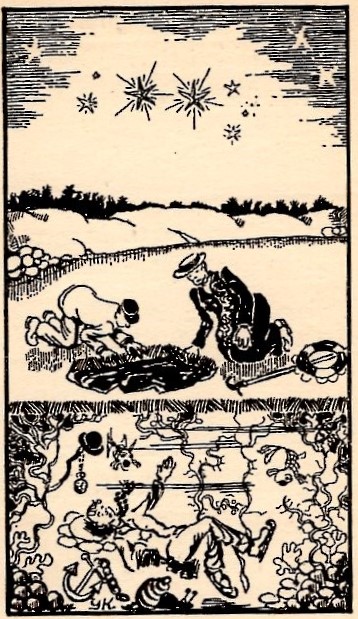

Fortunately, such a ban did not apply to everyone. Gustaf Fredrik Gyllenborg unleashes a whole group of boys on the ice in the twelfth stanza of his poem Vinter-qväde (1759):

Bron: Wikimedia

Vinter-qvädeSe fram! på detta vida hala, Hvad för en snäll och dristig fart! Se! hur' de yra gossar skala: Här röjer sig en kitslig art. En fram om skaran söker hinna: Han på sin skridsko tycks försvinna, Men halckar mitt i loppet kull. Hans ofärd andra segren gifver, Man gäck med fallna hielten drifver Och stranden blir af löje full.8 |

Winter songLook ahead! across the vast expanse, What a fast and daring ride! See! the vigorous boys dashing about: showing their teasing nature. One of them breaks away from the crowd: He seems to disappear on his skates, But falls in the middle of his flight. His misfortune turns others into winners, Poking fun at the fallen hero laughter is all around the shore.9 |

The relentless ice law

We must be careful not to paint too one-sided a picture of the (anti-)skating enthusiast. Although diaries and reports were written (and preserved!) by and for persons in higher positions, there is sufficient evidence that after 1750 the enthusiasm for skating among the average citizens did not decrease.

In the previous chapter we discussed the ice law of 1737, which had to curb risky behavior of skating enthusiasts. The fact that the law had to be carried into effect, and was adapted over time, reveals the persistent fancy of the Swedes for venturing out on the ice.

On January 26, 1773, the Stockholm Court of Justice implemented the 'ice law' of 1737 without compassion. The sailors Carl Wikman and Anders Lundqvist had strolled across the weak ice to Gamla Stan, Stockholm's Old Town. Wikman was sentenced to 10 pairs of canings. Lundqvist, however, had to pay for the adventure with his death. His body was not buried in the cemetery.11

In 1792, the regulation was somewhat adapted to the times. 'Anyone who ventures on the sea ice with or without ice skates - at least before a route with branches has been plotted - will face a hefty fine.'12 The caning has been replaced by a fine and it is no longer the minister from the pulpit who is giving the green light, but the government itself by means of setting out a course. One could still lose one’s place in the cemetery, however.

Bron: Skridskovisa, 1941

Illustrations: Yngve Kernell

An icy-cold ending

A short search of the dry listings on a number of genealogical websites on the internet shows, that despite these preventive measures of the government, not everyone returned alive from a skating trip:

† Anders Lem, sailor, drowned during 'glide paa Skøiter'13 (mid 18th century?)

† Peter Fenger drowned on January 11th in 1779, 20 years old, ‘på Damhussøen hvor han løb på skjøjter’.14

† Johan Jönsson, farmer's son from Löckerum, drowned in 1811, aged 20, when - on the same day his son was born - he fell through the ice while skating on the Soagöla in the town of Gamleby, Småland.15

† Peder Pedersen Slette, born 1764. ‘Død 17.2.1822 (druknet i Randsfjorden ved at løbe paa Skøiter)’.16

† Paal Jonssön, b. 1800, died, aged 27. ‘(gik i isen paa skøiter)’17

† Otto Månsson, born December 23, 1814. Died December 27, 1844 ‘av Drunkning. (Gick genom isen på skridskor)’.18

† Gerhard Severin, b. 1836. Died in 1849 'druknet under skøiteløbing i Kryptevik'.19

Although skating in the far north is more and more widely practised, we cannot yet recognize the popular entertainment as known from the Low Countries in it.

We can conclude that mainly trips were made, although fish biters and seal hunters will also have used skates if the ice was still free of snow. But what did those skates look like? In other words, what did that hapless mortal actually have at his feet when he was fished out of the hole?

Collection Nordiska Museet NM.0317618. Photo: Bertil Wreting.

Evolution in types of skate 1750-1800

It is not easy to date Scandinavian skates. They are seldom clearly visible on paintings or prints, few archeological finds are known and with skates from collections it is difficult to judge on their appearance. Many primitive skates seem older than they actually are, because they were often made with the help of second-hand materials by peasant smiths in the countryside. Fortunately, there are some skates with a year engraved in the footstock or other indication of their age. From this, in addition to the simple curl skate and possibly also the pointed hook toe skate, we can deduce two more models: the skate with a low, half-clad toe and the extremely long skate. The long skates can be divided into two variants: with binding and without binding. The skates from the latter category, without binding, are called rännskor.

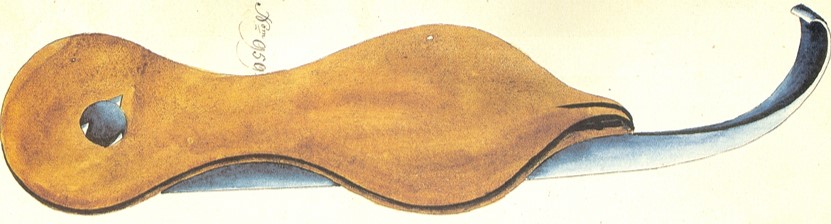

Low, half-clad toe

A skate with a footstock that goes all the way to the prow of the runner is quite rare in Scandinavia. In the low countries, this model has been around since the 16th century.1

On this type of skate with a low, half-clad toe the Scandinavians will have made their trips across the ice.

Three variations on this type have been found:

Low half-clad toe 1: Nordiska Museet NM.0114936 - Skricksko marked Ö

From Ovanåker near Edsbyn, Gävleborgslän (then Hälsingland). Ovanåker is located 255 km northwest of Stockholm. Ö possibly was the maker of the skate, which is referred to by the museum as hemsmide (homemade forging).

Date museum: 1750-1800. Date according to the depositor: 1775-1825.

Source: https://digitaltmuseum.se/011023592582/bokhylla

| Features NM.0114936: | ||

| Turned back little curl on the hook | Horizontal nail in the back of the footstock | Three round holes for straps |

| Width runner: 7 mm in front, 5 mm at the back | Stamped Ö in the curl | Length: 35 cm; height curl 6.5 cm |

Tiny curl on the hook of the skate

Tiny curl on the hook of the skate

A small curl on the hook, as can be seen at NM.0114936, was applied more often to Scandinavian skates. Both Biegelaar-1 (see below) and the two pairs with long wooden toes (NM.0097500 and NM.0097559) from the vicinity of Hjulsjö, Västmanland in Sweden (see next chapter) have been carried out with it.

Since the locations of the skates are more than 200 kilometers apart, the tiny curl seems more a time-bound than a regional phenomenon. We can date this trend from around 1750 to 1850.

Biegelaar-1 has a tiny metal rod inserted through the minute curl that strengthens the connection between the hook and the wooden footstock.

Low half-clad toe 2: Biegelaar-1

The footstock of the curl skate that used to be part of the Biegelaar collection (now collection author) also extends to the prow of the runner. Like the previous skate (NM.0114936), the hook is forged into a tiny curl that stands out visibly above the footstock. An iron pin has been inserted through that curlet, a unique application to ensure the connection between runner and stock at the front. At the back, the runner is double-folded and attached to the 7.8 cm wide footplate with a horizontal nail.

Origin: Sweden

Dating Jan Biegelaar: 1750-1800. This skate might be a little older than NM.0114936.

The mark in the footstock ![]() may be intended as an indication for the left skate. Compare with NM.0071614.

may be intended as an indication for the left skate. Compare with NM.0071614.

| Features Biegelaar-1: | ||

| Turned back curlet upon the hook | Lenght: 35 cm | Width footstock: 7.8 cm |

| Double-folded runner at the back | Mark |

© Monumenten en Archeologie, municipality of Amsterdam

Double-folded runner

The double-folded runner, visible at Biegelaar-1, is the oldest fastening technique of the footstock to the runner we know. This method was already used in the Amsterdam and Dordt skates, both from the 13th century.

%20-%20kopie.jpg?1621842497278)

At the end of the Middle Ages the double-folded runner still occurred.

Afterwards, the runner was single-folded, until, in the course of the 17th century, the heel screw would replace it.

It is striking that the technique with double-folded runner was used in Scandinavia for much longer than elsewhere.

Low half-clad toe 3: Erwin Daniel-10 B.POS

On account of external characteristics the primitive-looking skates from the collection of Erwin Daniël, Emden, Germany also belong to type low, half-clad toe. The pair are from Norway.

%20prim.%20doorl.%20bind.%20bovenover-corr_1.jpg?1619430579075)

Unlike both previous variants, the wooden toe of the footstock lies more or less loose on the runner. The hook, which rises vertically through the footstock, is bent on top. This connection also occurs with a long skate from Daniël's collection (Daniël-11) and seems to be a typical Norwegian custom. The footstock has notches at the four strap holes, three of which run over the stock. The skate is hard to date.

Marks: B. POS and H (høyre = right) in the foot pile; X in the toe of the runner. This stamp X presumably does not refer to a maker.

Binding through and over the footstock

The typical binding, in which rope, ribbon or belt is braided both through and over the footstock, seems to be a specific Scandinavian feature. This method, visible in pair Erwin Daniël-10 B.POS, we will be seeing more often in skates of different types. The binding through and over the stock was mainly used in Sweden until around 1870, although in the Norwegian province of Sør-Trøndelag, which borders Jämtland, ice skates with such a binding method have also emerged.

The advantages of this way of binding are twofold: the shoe slides less easily from the footstock, while in turn the shoe itself keeps the binding in place.

A variant of the binding through and over the stock is the one with an open 'window' through which the binding is visible.

This method of attachment does not occur in the low countries or elsewhere, although it could have been applied to the Dordrecht skate from the 13th century. However, any direct influence back and forth seems to be out of the question, because the intervening period is too large.

Long skate

In rural central Sweden, the development of the skate seems to have gone its own way. With their extremely long runners, the bottom of which was nevertheless almost half as narrow as that of Dutch runners, the long skates completely deviate from everything that was common in the rest of Europe around that time.

The Nordiska Museet in Stockholm has quite a large number of these long skates in its collection. The relatively narrow runners are about 55 to 70 cms long. They come from Dalarna and three more provinces just west and north of it.

The rännskor on the left are 66.4 cm long, the long skates in the middle are 58 cm long, and the curl skates on the right are 31.6 cm long. These are NM.0098472, NM.0045640 and NM.0086629 respectively, all from Nordiska Museet, Stockholm.

Ref: Gösta Berg - Isläggar och skridskor in:

Fataburen, Nordiska Museets och Skansens Årsbok,1943, p. 83

A direct influence from other countries seems out of the question, because as far as is known skates of these excessive dimensions did not occur elsewhere in the world.

With most long skates the wooden footstock encloses about 85 % of the runner, which thus gives extra firmness. That certainly was not an unnecessary luxury with blades that were only two to three and a half millimeters wide.

The stocks - apart from their pointed noses - are usually remarkably straight in shape, somewhat reminiscent of old skis. Skis were already used in the north of Scandinavia thousands of years ago and have probably served as a model for the long skates. Only a single pair (NM.0098472) has the stock narrowed at the rear as well, apparently to please the eye or to lighten the skate.

Furthermore, it is noticeable that long skates of the same pair are never exactly the same length. The difference ranges from 0.7 to 2 cm per pair. Clearer evidence for them being hand-forged products will be hard to find.

All eight pairs of long skates in the Nordiska Museum have a bare upright prow that almost always ends up into a small curl. Only one pair (NM.0102679) have that curl forged wide.

At the back, the runner sometimes goes all the way to the rear of the heel, where the blade has been folded or even double-folded in a primitive manner. Nevertheless, the design of the curl and the long, thin runners show that we should not underestimate the craftsmanship of the makers.

In later models, the runner ends mid-heel thanks to an attachment by means of a heel screw or nail.

The long skates should not be confused with other large types of skates such as the snow skate with its much wider bottom or the often even longer 'bakkeskeiser' or 'rennarband' from Norway, which do have narrow runners, but whose use differs completely. I will cover snow skates and bakkeskeiser in a later chapter, as well as the long skates that were used in ice surfing.

Based on the binding, we can distinguish the long skates in skates with strap holes and the so-called rännskor, without strap holes. These rännskor could only be pushed forward by poles; for the long skates with strap holes, the use of poles is not certain.

From the position of the footrests (clamps) and the holes for the binding, we can see that the shoe was never placed completely on the back of the footstock.

Split hook

Possibly due to wear on the wood of the footstock, the hook that connects the wood to the runner at the front, has become somewhat exposed in most long skates and is therefore clearly visible. The design of those hooks turns out to be quite uniform. In almost all cases, the hook is not forged or hammered out, but partly separated from the runner with a cleavage chisel or similar tool (klyvning). This is in contrast to the more common technique of forging such a hook, namely splitting some iron off from the front, where the runner usually becomes lower anyway, and then forging the cut-away iron backwards to form the hook.1

Long skates with strap holes

The long skates with strap holes from the Nordiska Museum were all brought in from the area south of Östersund in Jämtland. There are three samples in the collection of the Nordiska Museet in Stockholm that belong to this group:

Long skate with strapholes 1: NM.0045640

The oldest dated pair is believed to be from 1775, the year engraved in the footstock of the left skate. The pair turned up in the municipality of Berg in Jämtland, 442 km northwest of Stockholm, but were possibly made elsewhere.

Ref: documentation Nordiska Museet, Stockholm

Both skates have holes in three places, both horizontally and vertically, for a binding of rope, which goes partly through and partly over the footstock. From the position of these holes we can deduce that the shoe was not placed entirely on the back of the stock. Therefore the upright hook, that goes right through the footstock and thus forms a fairly primitive connection at the rear, presumably did not end up in the heel of the footwear.

The footstock of the right skate, recognizable by the beautifully shaped A engraved in the stock is a bit longer than the left. The A is probably an initial of the owner's name, not the maker’s.

The uncovered toe protrudes almost 8 cm. Despite their length, the skates are surprisingly lightweight.

| Features NM.0045460: | ||

| Height curl: 3 cm | Length: 59.5 cm | Width runner: 2 mm |

| Split hook | Three strap holes over the stock | Vertical hook through heel footstock |

| 1775 engraved in left stock | A engraved in right stock | Very lightweight |

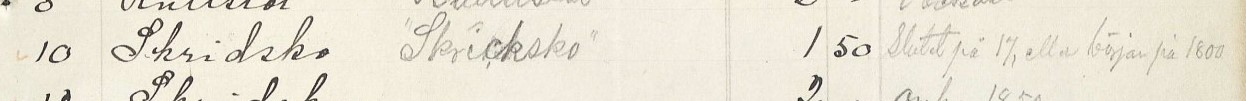

Long skate with strapholes 2: NM.0102679

Source: enclosure with https://digitaltmuseum.se/011023556632/skridskor

The pair of 'skrickskor' NM.0102679 also have upright hooks at the back sticking through the footstock. They are bent on top of it. The stock has two round holes for a binding of cable rope (trossar) and belts. This is the only pair of long skates with widely-forged curls.

The couple are from Hede, Härjedalen, Jämtland, about 440 km northwest of Stockholm.

According to the written notes taken when these skates were presented to the museum, a pole (staff) would have been used for pushing. See image of these notes on the right.

| Features NM.0102679: | |

| Length: 57.9 cm | Width runner: 2 mm |

| Height curl: 5.5 cm | Vertical hook through the back of the footstock, bent on top |

| Marked H and HW in footstock | Widely forged curl |

| Two round strap holes through and over the stock | |

Long skate with strapholes 3: NM.0100506A

'Skricksko' NM.0100506A differs from the previous pairs in that the runner has been folded at the rear. Apparently, this skate does not form a pair with NM.0100506B, because the latter has no strap holes and should therefore actually be considered a rännsko. We know so little about the use of long skates, however, that we should not rule out a connection between the two skates. It could be that the user had one skate (A) attached to one foot while the rännsko (B) was loose under his other foot. In that case, a pole must have been used for propulsion.

Rännsko (?) NM.0100506B (bottom, without holes for straps)

The skates are from Åsen, Lillhärdal, Härjedalen in Jämtland, about 320 km northwest of Stockholm.

| Features NM.0100506A: (for NM.0100506B see below at Rännskor) | ||

| Length 55.4 cm | Two strap holes through and over the stock | |

| Curl has been bent sideways | Runner has been folded once at the back | |

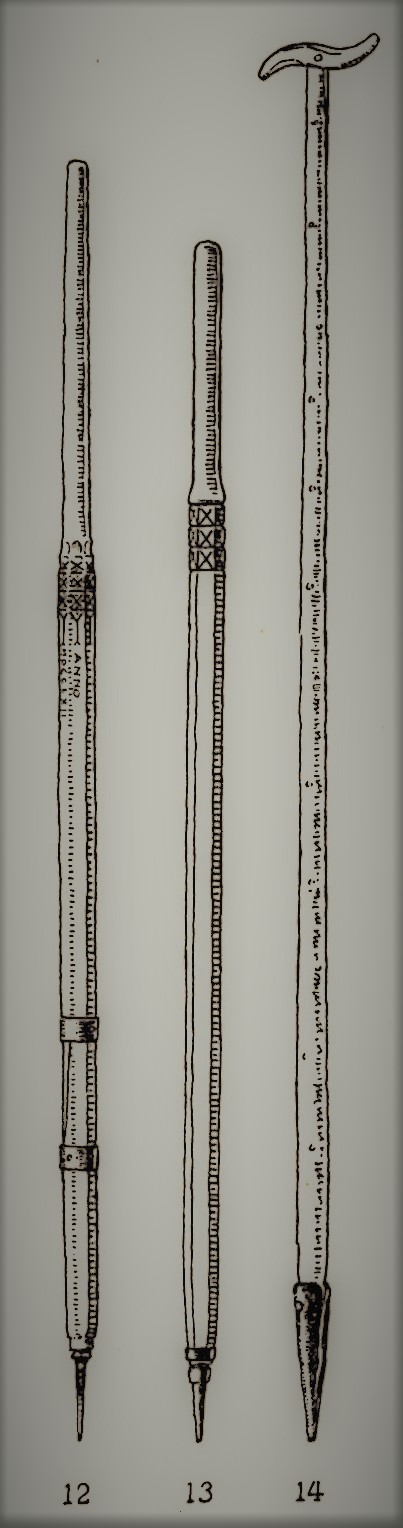

Nr. 14 belongs to rännskor NM.0098472.

Source of drawing:

Gösta Berg - Isläggar och skridskor in: Fataburen, Nordiska Museets och Skansens Årsbok, 1943, p. 87

Rännskor, Long skates without strap holes

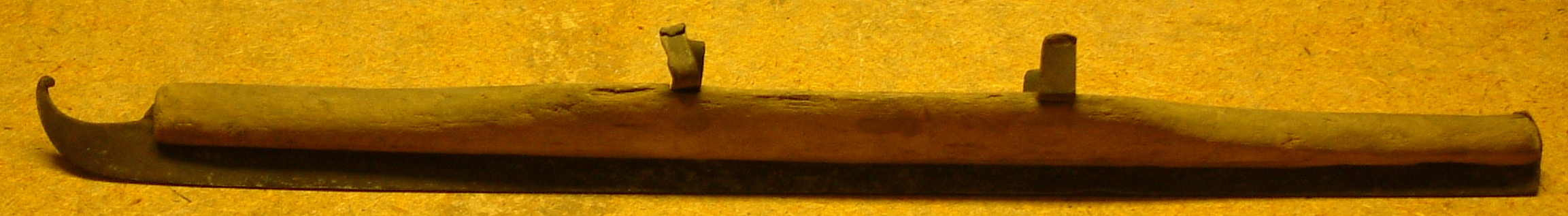

The 'rännsko', literally meaning ‘running shoe’, or 'rännskridsko' is a long skate without strap holes. Since a sideward push off and making strokes is impossible with skates without bindings, poles for pushing off had to be used. Such a pole, known as 'pikstav' or 'rännskostav', has been preserved for skates in Nordiska Museet specifically documented as 'rännskor' (NM.0115504 and NM.0098472).2 Instead of binding holes, the rännskor do have one or two transverse iron clamps, which had to prevent the shoe from moving sideways from the footstock. How footwear was prevented from slipping backwards is unclear.

Although the only dated rännskor (NM.0100140) date from 1818, it is quite possible that as a model it is from the same period or even older than the long skate with binding holes.

It is striking that most rännskor are from the vicinity of Lake Siljan in Dalarna, while almost all long skates with binding have been found more than a hundred kilometers further north. That is why it seems that the distinction between long skates with and without bindings could to a large extent be explained on account of them being local variations.

One pair of skates without strap holes from a private collection (Daniël-11) is said to be Norwegian.

Rännskor 1: NM.0100140

The pair of rännskor with the year 1818 engraved in the footstock is from Östansjö, Lillhärdal, Härjedalen, Jämtland. Östansjö is located about 348 km northwest of Stockholm.

| Features NM.0100140: | ||

| Split hook | Single foot clamp, fixed with a nail |

.jpg?1619509386955)

|

| Respectively cramp and folded iron at the back | Engraving in footstock OMS ^1818 ^ | |

| Length: respectively 56 and 61 cm. | Width runner: 3.5 mm halfway the skate | |

Rännskor 2: NM.0115504

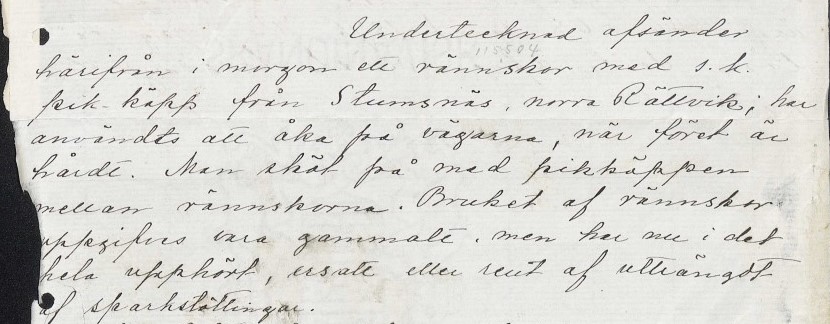

NM.0115504 described as 'rännskor med pik-käpp' (pole) are from Stumsnäs, Rättvik in Dalarna (near Lake Siljan). Stumsnäs is located about 243 km northwest of Stockholm.

Source: enclosure with https://digitaltmuseum.se/011023594220/rannskor

The description of rännskor and pik-käpp NM.0115504 (pictured right) indicates that they were used on roads with a hard top layer (crust of snow). One pushed forward with the pole between the rännskor. Their history goes back a long time, but they were largely a thing of the past in 1910 and replaced by, among other things, the sparkstötting (a kind of chair sleigh).

In an overview of newly acquired objects of the Nordiska Museet, these skates are described as 'snow skates with pole'.3

| Features NM.0115504: | ||

| Length resp. 69 en 70.5 cm | Width runner: 3 mm | Height curl: 5.1 cm |

| Two clamps on both skates | Vertical hook through stock at the back | Split hook |

Rännskor 3: NM.0071614

This pair was presented from Bråmåbo, Sollerö in Dalarna, also located at Lake Siljan. This location is 155 miles northwest of Stockholm.

| Features NM.0071614: | ||

| Length: resp. 53.8 en 54.5 cm | Width runner: 3 mm | Height curl: 5.3 cm |

| Marks on both footstocks | Runner double-folded at the back | One iron clamp each4 |

Source: documentation Nordiska Museet, Stockholm

Source: documentation Nordiska Museet, Stockholm

The markings on the skates may be intended as indications for the left (longest) and the right skate (shortest).

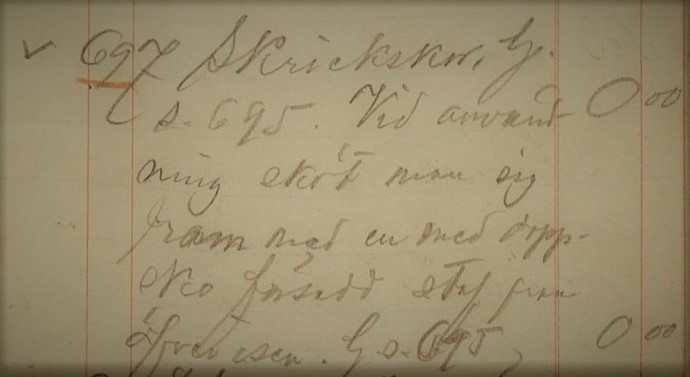

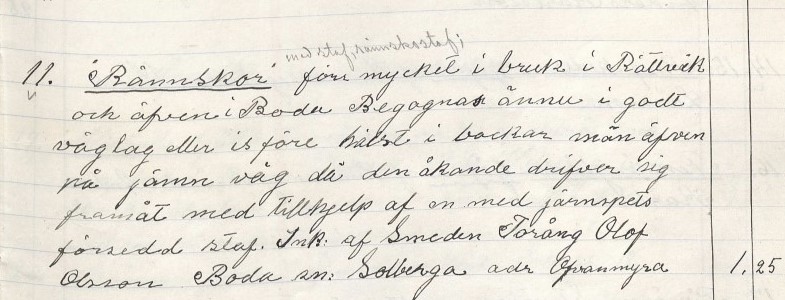

Rännskor 4: NM.0098472

The pair NM.0098472 are from Boda, Rättvik in Dalarna, about 15 km northeast of Lake Siljan and about 243 km northwest of Stockholm.

Source: enclosure with https://digitaltmuseum.se/011023545214/skridskor

The notes recorded at the time of the acquisition of these rännskor in 1904 (picture right) state that these skates were still in use at that time in both Rättvik and Boda, especially in the hills, but also on passable roads and on ice.

On flat terrain, the skater moves with a stick equipped with an iron tip.

The rännskostaf (pole) that belongs to this pair has also been preserved. See no. 14 in the image with the three poles above.

The skates were purchased by Nordiska Museet from the blacksmith Jorång Olaf Olsson from Ovanmyra near Sollberga, municipality of Boda. Olsson is probably not the maker of the skates; otherwise that would have been mentioned.

| Features NM.0098472: | ||

| Length: resp. 64.5 en 66.4 cm. | Width runner: 3 mm | Height prow: 4.6 cm |

| Double folded runner at the back | Two clamps each skate | Narrowed footstocks towards the ends |

Rännskor 5: Daniël-11

The reddish-brown, 66 cm long skates from Erwin Daniel's collection are believed to be from Norway. In terms of the shape and length of the footstock, they resemble the previous pair (NM.0098472). Rivets have been used for both the footrests (clamps) and the connection of runner and stock at the back. Because at the back the runner is shorter than the stock, this skate could be from a later period. The hook rises vertically through the wooden nose and is then bent over. Unlike the other long skates, the footstock is not so much worn out at the bottom, while the sides show bald patches instead. As if they had been used at a very oblique angle, as for example with the 'skridskosegling' (ice surfing). However, this seems to me to be a highly unlikely explanation for skates without binding. An alternative explanation is that the bald patches were created by use of these rännskor in the snow.

%20lange%20schaats%2066cm.jpg?1619516187168)

Rännskor 6: NM.0100506B

It is a mystery how NM.0100506B, a long skate without binding holes or footrests, was used. The only thing that can be thought of is 'sparkning', a stepping method that was also used in seal hunting with the help of a 'skredstång' (pole) on a surface that was too rough for skating.

At first sight NM.0100506B does not form a pair with long skate NM.0100506A. See my comments there.

This skricksko, like NM.0100506A, is from Åsen, Lillhärdal, Härjedalen in Jämtland, about 320 km northwest of Stockholm.

Source: documentation Nordiska Museet, Stockholm

| Kenmerken NM.0100506B: | ||

| Length: 60.5 cm | Width runner: 3 mm | Height prow: 4.8 cm |

| Without strap holes or foot clamps! | Engraved mark SoS | Split hook |

Use of the long skates

Skates with a length of 50 to 70 cm are clumsy things, therefore there must have been a good reason to develop them. There are, however, very different opinions about the use of the long skates.

Professor Gösta Berg indicated that the rännskor in Rättvik and other municipalities around Lake Siljan were also used on snowy country roads.4 They were even described as snow skates in 1911.5 An unfortunate term because the wide iron strip under the 'real' snow skate does form a very large contrast with the narrow runner of the rännskor. According to Berg, long skates were mentioned in the 1820s by the poet Elias Sehlstedt from Härnösand on the east coast in Norrland and, according to other sources, also occurred in Västmanland and Romerike (Norway).6 Due to the possible confusion between rännskor and snow skates, we must be careful with the interpretation of written sources that are not supported by objects or images.

The long skate with footclamps from Rättvik, in the display cabinet of the club building of the SSSK in Saltsjöbaden (not pictured), differs slightly from all previously discussed long skates. The uncovered iron toe of the skate protrudes much further. The caption accompanying the skate reads: 'Rännskridsko or isränna from Rättvik. Too long to make strokes with. Used with a tail wind on the lake or on icy roads with one or two poles.'

Christina Norin recalls that lumberjacks in the vicinity of Mockfjärd - just south of Lake Siljan - used the long skates to guide their horses, that pulled the timber-laden sleds through the snow.7

Wear on the front and bottom of the wooden footstock - which is the case with almost all long skates - supports the view that the long skates have indeed also been used in fairly deep snow. Moving one’s poles by elbow steam like a cross-country skier one could apparently go along fairly well. But that was not all. Because of the runner under the wooden footstock one could continue on the ice with the same technique. The rännsko therefore can be considered a kind of all-terrain ski-skate, but due to its sharp and thin runner it was of course not very manoeuvrable.

Risk spreading in the extraction of bog ore?

Did the length of the skates also play a role because of risk spreading on thin ice? The very narrow, and therefore relatively light runners and the use of a particularly light type of wood, together with the extreme length, do indicate the importance of spreading as little weight as possible over a large base.

The sites where the long skates from the Nordiska Museet were found are limited to a number of areas in central Sweden. In all of those areas bog ore was won. Therefore I wonder if the long skate was used extracting it. From north to south the areas concern Jämtland (two pairs from Härjedalen and two pairs from the region north of it) and the vicinity of Lake Siljan in Dalarna (three pairs). Besides we could add the two pairs of long all-metal skates from adjacent Hälsingland, which will be covered in the next chapter.

All sites of long skates are located in an environment consisting of lakes and swamps. It is therefore tempting to play with the idea that the long skates were used in the extraction of ore from marshes (myrmalm) and lakes (sjömalm). Although ore has been extracted from mountain quarries (bergmalm) in Norway and Sweden from around 1100 AD, the 'wet' exploitation has remained significant for quite a long time, especially - but certainly not exclusively - in the three provinces mentioned.

Traditionally ore from bogs and lakes was mostly mined in winter. Miners went on the ice as soon as it would bear them and stuck through it with their poles, hoping that the tip of it would show a rusty-brown color. If the pikkäpp had an iron tip, one relied on the sound for identification of a site. Places with ore were marked with branches.

Due to their great length and low weight, the rännskor would have been particularly useful at this stage. Also the pikkstavar from Dalarna (see above) fit in very well with this method of working, although of course the poles were just as well used for propulsion.

after a drawing by Nils Melander in the annals of Jernkontoret

Ref: Svenska Järnstämplar, supplement, p. 45

Later in the winter, when the ice was thick enough, the miners returned to the demarcated places. With the ice axe, a bite was chopped about one and a half to two meters in diameter, which was widened even more at the bottom. This made it a bit easier to work up the ore from the usually fairly shallow water, where it was lying on the bottom in loose clogs. For this purpose, long rakes and other specialized tools were used. To shelter his sweaty body from the icy wind, the ore miner had set up a wicker screen. Goat wool mittens and clog boots had to keep hands and feet warm.

If my theory is correct, both the long skates from Bråmåbo (site of pair NM.0071614) and those from Stumsnäs (site of pair NM.0115504) could have been used for winning ore from Lake Siljan, for both places are located directly on its shores.

In the 18th and 19th centuries there were still many järnbruk, small iron factories such as Siljansfors, around the lake. At that time, however, most ore already came from quarries, while marshes and lakes gradually contributed less and less. From Lake Siljan itself, as we can conclude from a 1839-report, no sjömalm was won in those years. According to the spokesman from Dalarna, the only lake ore came from Oresjön and Orsasjön8 in that province, not very far from Boda (municipality of Rättvik), where the long skates NM.0098472 are from.

As mentioned, also the other long skates all come from places in a watery or swampy environment. I have not been able to determine in all cases whether ore occurs at those sites, but that may well be the case. Geographical names near all places where long skates were found, are very often composed of 'myr' or 'malm' or even 'malmmyr', which says enough about local soil conditions.

All in all, there seems to be sufficient evidence to further investigate the possible link between long skates and ore extraction.

Imports from Germany

From the Factura-Büchern 1780-84 of shipping house Engelbert Luckhaus from Büchel (near Remscheid in Bergische Land, Germany) it appears that there were limited exports of ice skates to Christiania (present-day Oslo) in Norway in those years. Like other small hardware, skates were shipped in barrels via Hamburg. Skate makers that were active in the vicinity of Remscheid at the time were Heinrich Voss from Hölterfeld (mark: eagle with letters HV) and Peter Wilhelm Brand senior from Hütz (mark: flowerpot). They used commercial agent Luckhaus to market their skates outside their own region.9

Presumably, the sudden Norwegian preference for German imports can be explained by a relatively new invention: the hollow or gutter, a groove down the length of the bottom of the blade that creates two edges facilitating grip on the ice.10 Apparently the Norwegian blacksmiths themselves had not yet managed the technique of hollow grinding, which was considered an improvement. It seems that especially the high 'Hohlbahnschlittschuhe' (hollow-ground skates) have found their way north.

These hollow-ground skates came in various versions, the names of which we know, but not always what they looked like. Presumably over time there have been several names for the same type of skate.

In the years 1778-79 the following models with a hollow groove were made by Voss in Remscheid:

|

Ordinäre große Hölzer (ordinary large wooden skates) |

104 pairs | 57 % |

|

|

Mittelhölzer (medium size wooden skates) |

29 pairs | 16 % | |

|

Glatte Breithölzer (polished wooden skates with wide footstocks) |

35 pairs | 19 % | |

|

Hölzer mit Kupfer (wooden skates with copper inlay) |

15 pairs | 8 % |

It is striking that the skates were distinguished according to the shape of the footstock. We are not sure whether the 'Ordinäre große Hölzer' (ordinary large wooden skates) corresponded to 'Ganzhölzer' (skates fully covered by wood) or to so-called 'Langhölzer' (long wooden skates), which were made a lot in the 1760s.10

The Musterbuch (1789) of Johann Schimmelbusch from Solingen depicts four different models of ice skates, which give us some idea of what was for sale at the time. The violin-shaped wooden footstocks seem quite wide in all cases, and the prow consists either of an angled hook toe, rounded off with ornamental forging, or of a rather modest curl. Runner and stock were connected together at the heel with a three-pointed screw.11

In the bottom of the runner the hollow groove is visible.

%20-%20kopie.jpg?1619769959106)

Musterbuch Schimmelbusch,

model 957 detail

Whether the export skates for Christiania had a hook toe or curl will probably never be determined, but there is no doubt that the runners stopped halfway under the heel of the violin-shaped wooden footstock, where a screw connected them. Skates of this model and from this period we do not find in Scandinavian museums.

The average factory prices for flat and hollow-cut skates from that period are known12, and were respectively 0.41 Marks per pair and 0.64 Marks per pair. With factory prices and export figures it is possible to roughly calculate the volume of those exports to Norway. In 1782, for example, it must have been between 13 and 20 pairs, depending on the number of regular skates and the more expensive hollowed skates, which probably prevailed.

By the end of the 1780s, orders for Christiania and neighbouring Drammen were about three times as large (see table).13

| Location / Period | Exports in Marks | # of pairs / year |

| Christiania 1782-1784 | 8.5 | 13 to 20 |

| Christiania 1788-1790 | 24.3 | 38 to 59 |

| Drammen 1788-1790 | 25.2 | 39 to 61 |

However limited in quantity, at least there was a certain demand for foreign skates in Norway. It is possible that German skate makers gradually adapted their product to the specific wishes of the Norwegian consumer, as they did for the Dutch market for example.14 However, there is no evidence of that. As we have seen, the imports actually concerned only very small numbers.

Although many retailers in Stockholm sold foreign hardware - the quality of domestic products left something to be desired at the time15 - nothing is known about imports of German skates into Sweden before 1800.

For the period after 1795, no detailed export data are known from German sources. Exports were severely impeded from 1806 to 1814, when Napoleon turned Europe upside down. Later in the 19th century, despite the emergence of its own skating industry, Scandinavia would become one of the most important outlets for the skate makers from Remscheid.16

In the next chapter (1800-1857) we will see that Scandinavian skate makers eventually started to imitate the German model with a hollow groove.

Skate makers 1750-1800

For this period we do not know the names of any Scandinavian blacksmiths or iron works that made skates. The most we can do is present some candidates.

Candidate skate maker Ö from Ovanåker, near Edsbyn

Source: documentation

Nordiska Museet, Stockholm.

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm

NM.0114936

The mark Ö in the curl of the skate from Ovanåker with a low, half-clad toe (Nordiska Museet NM.0114936) may refer to the name of the maker. According to the museum, this is a product of hemsmide, homemade forging. Nothing is known about maker Ö. If my assumption is correct, he must have been a local blacksmith or allmogesmed (peasant blacksmith) from the Edsbyn area.

Candidate makers of long skates, from Lima or Hedemora in Dalarna

Thanks to the careful notes of the Nordiska Museet, the long skates can be brought home to Dalarna and some provinces north of it. Unfortunately, the research stops in finding out the makers. The initials that were sometimes carved into the footstock probably related to the former owners of the skates and not to the blacksmiths who made them.

The runners of the long skates from this period are nearly always unmarked as well. Most likely they were made by village or peasant smiths rather than by larger iron works or metal craftshops. Probably only the rod iron for the runners came from a 'bruk' or 'verkstad' in the neighborhood.

Local smiths did not care much for a proper and stylized finish of the connection between runner and stock at the back. Screws, for instance, were not even used. Once again, it becomes clear that the long skates were products from occasional makers.

Scythe smiths?

Nevertheless, they were craftsmen who mastered the technique of steeling well, because forging a 2 to 3 mm wide runner over a length of half a meter and more certainly was a nice feat of blacksmithing. I would therefore not be surprised if the famous scythe smiths from the Lima or Hedemora areas in Dalarna turn out to be the makers of the long skates.1 A report from 1764 states that scythes and other forgings from Lima and Hedemora were marketed via barter in Härjedalen (Lillhärdal?), Särna, Värmland, Västmanland, Norrland and part of Uppland. From Härjedal most of the goods were even traded onward to Norway.2 What a range! Unfortunately, I cannot prove that this also applied to ice skates, but that assumption is by no means unthinkable.

No screws in stock?

With almost all skates from this period, it is noticeable that the blacksmith apparently made great pains of the prow of the skate, but made light of the heel connection. As if all creativity had to be put in the curl and forging a screw eye was too much to ask. In fact, according to a price list for forgings from Hedemora in Dalarna from 1758, screws were not even made there. Including horseshoe nails, some six different types of nails are mentioned, but no screws whatsoever. About six years later, the overview of forgings from the area shows the same picture: dozens of farriers manufacture horseshoe nails, while about ten smiths make ordinary nails, but there is no one who takes care of screws.3 For the rather one-sided assortment of horseshoes, scythes, axes and simple agricultural tools, the peasant smiths did not need screws at all. No wonder that for an occasional product like a pair of skates they used nails and cramps instead of ordering screws. This situation was, of course, particularly true for remote regions in provinces such as Jämtland and Dalarna, but will have occurred elsewhere too. This gives us a starting point to distinguish skates from peasant smiths from those by the 'järnmanufaktur' (metal craftshop) in later periods. If skates were made at all in those factories around 1750, production must have been quite insignificant. The skate is not mentioned once in inventories among artisan metalworkers in Sweden between 1754 and 1764.4

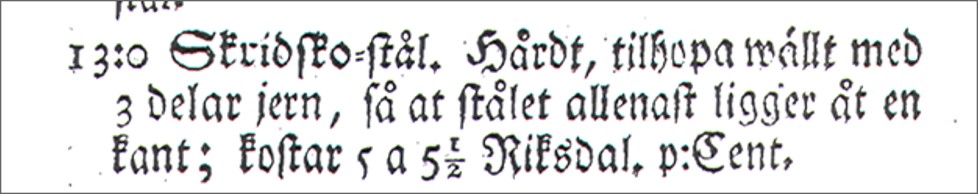

Candidate skate makers from Eskilstuna Fristad 1771-1800

In the mid-18th century, metal working in Sweden was still well behind places like Sheffield in England and Remscheid in Germany. Early foremen of the iron industry undertook study trips to the Bergische Land in Germany, among other places, and became aware of production methods that were completely unknown in Sweden. They published their newly acquired insights in their homeland. In 1772, for example, Sven Rinman mentioned in his book Jern- och Stålförädlingen (Iron and Steel refinement) that in Germany at the time separate types of steel were made for instruments, swords, knives, planes and the like. He does not elaborate very much on steel for skates: 'it is hardened and combined with three parts of iron so that the steel is completely on one side. It costs 5 to 5.5 Rijksdaalder per 100 steel pounds'. At that price skate steel was considerably cheaper - because less hard - than, for example, sword or knife steel.4

Source: Wikipedia

From Rinman’s listing we can deduce that skates were probably already made in Eskilstuna, but that a specific basic material such as ready-made skate steel was not yet known there. Smithies that, as in Remscheid, were fully dedicated to making skates, did not occur, according to the surveys of professions of 1755, 1769 and 1770.5

Source: Wikipedia

On the advice of Rinman and in particular Samuel Schröderstierna, a Fristad (free town) for iron, steel and metal refinement was established in 1771 for which the state bought up the forges and grinding works of old Carl Gustafsstad. The starting points were ambitious. In order to compete with foreign countries, they wanted to attract experienced forces from England, to set up new production methods according to foreign model, to abolish the old guild system and to introduce piecework. With exemption from excise duties and taxes, know-how had to be lured to Eskilstuna.

Although it proved far from possible to achieve all idealistic objectives, the number of workshops and employees increased considerably in the following years. The measures attracted not only skilled blacksmiths from other places in Sweden, but even knife and sword smiths from Solingen in Germany.6 Eskilstuna steadily grew into a major domestic producer of knives, locks, scythes, axes, files, and the like.7 Ice skates were probably also made, although no skridskosmed (skate maker) was specifically mentioned in the survey of professions of 1806.8 That was not surprising in a country where skating had not yet taken off, the rural population was self-sufficient (peasant smiths) and the people in the city often preferred imported foreign ware. The skate was still no more than a by-product.

Iron working in Eskilstuna

Three-leaf clover stamp 1740-1840

Source: Hermelin CGS

The blacksmith was able to buy his rod iron in a number of ways. Directly from the iron smelters, through intermediaries from mining areas or Stockholm, or through his 'förläggare' (financier and buyer) from Eskilstuna itself.

This rod iron was then processed into wrought iron at the so-called 'tjänsteverken' (a kind of public works) in the Fristad. This authority had already been established at the time of Carl Gustafstad's manufakturverk and was intended to meet the needs of the joint workshops. The 'tjänsteverken' were gradually expanded over the years and in 1800 consisted of three 'knipphammare', where rod iron and steel were rolled and preprocessed for different purposes, and three grinding houses, which were rented to different grinders.9

Steel, a requirement for edge tools (and for sharp skates), was made in Eskilstuna from 1656. Flat bars of iron were placed in stone containers with crumbled charcoal and heated in closed ovens until they were enriched into steel, which then received an extensive finishing. From 1740 to 1840 all this so-called 'brännstål' from Carl Gustafstad was marked with a three leaf clover.10

From 1825 onwards, cast steel would gradually become important and replace 'brännstål'.

In the next chapter (1800-1857) we will get a better view of the skate makers in Scandinavia.

Where do we go from here?

Back to the main menu of Scandinavian skates

Please present me the next chapter right away: Scandinavian skates 1800-1850

Straight away to The craft industry in Eskilstuna 1800-1850