Period 1800-1850

Overview

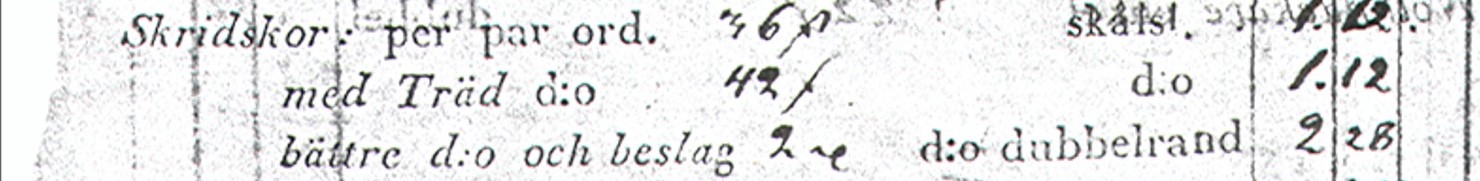

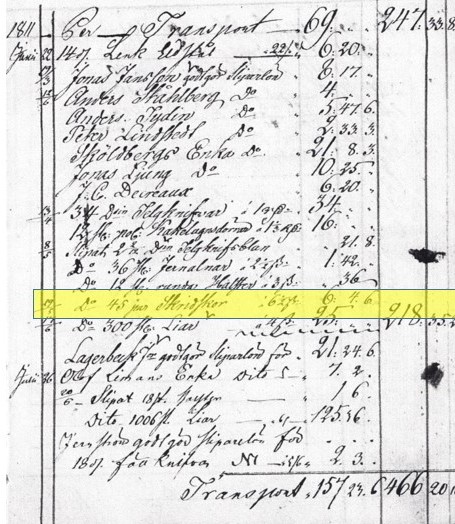

The skaters near open water have ignored the cordon of branches planted in the ice.

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm NMB 482. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Skridsko-wisa"Hur glad och lustig är wår fart wid sken af tända bloss! Deruppe Carlawagnens ljus, och böljan under oss! Med jernbeslagna dansar-skor, på hafwets spegelplan, wi skynda till en nordisk bal. - Raskt, bröder! sätten an."1 |

Skating song"How happy and joyful is our speed in the shine of a glowing torch! Above us the light of the Big Dipper, and below us the waves! With iron-studded dancing shoes, On the flat mirror of the sea, Let's hurry to a Nordic ball – Fast, brethren! Make a move." |

It is quite difficult to get a good picture of the developments in the field of skating in Scandinavia around 1800. Ice clubs or rinks were not there yet. Manufacturers hardly advertised. The age of skates in museum collections is usually unknown or not given. Fortunately we do have some references in literature and the visual arts however.

Collection Nordiska Museum, OMÄRKT

Foto: Peter Segemark

Develish pain

Before 1800, skating in Scandinavia, apart from the raw reality of farmers, fishermen and hunters, was mainly child's play and occasionally a hobby of a well-to-do citizen. Only in the course of the nineteenth century it would catch on a little more widely, and even then development was initially slow.2 This was largely due to the inept model of skate, which with its high prow and mid-heel runner caused numerous hooks and falls.3

Even though a French source spoke highly of 'les brides suédoises' (the Swedish reins)4, the binding was still very poor at the time. Skates never really were comfortably strapped to the feet, unless you pinioned the 'snøre' (ties, rope laces) that ran over the instep with the help of a 'Træpind' (piece of wood). "But no skater will ever forget the devilish pain if your feet had been pressed for too long by laces that were too tightly drawn," old Mikkelsen from Trondheim recalled in 1920.5

Mission accomplished

steel engraving

Still, there were plenty of lovers of skating and other winter fun.

In the very harsh winter of 1838 Frederika Bremer, writer and an early champion of women's rights in Sweden, tried to win over the Dane Hans Christian Andersen, who had at that time not really broken through as a fairy tale writer yet, for the Swedish outdoors: 'Come and see the winter scenes in our 'Bruken' (factory villages), our 'skridskotåg met faklor' (torchlight parades on skates), our sledding parties ... '.6

However convincing Bremer sounds, fun on the ice usually knew only sparse moments. Sometimes it was not possible to skate for winters in a row when snow fell early in the season.7

No wonder that gårdmann Mons Bentsen Toverud, who had his own farm, got an itch to go skating when the entire Randsfjord in Hadeland, north of Oslo, was shining like a mirror one winter day around 1840. This was a real opportunity. That early Sunday morning he skated about thirty kilometers north to Hov, where he went to church. But the moment the priest greeted the faithful, Mons sneaked out of the church again, tied his short, thick irons underneath and was gone. After another thirty kilometers, but now to the south - he must have had a favourable wind - he shot into church again in Næss near Brandbu only to ... leave right away once more. It seemed he had wasted his powers by now, because youngsters sprinted past him when leaving the town. Still, it wasn't long before Mons, deeply hunged over in his characteristic style, regained his strength and left the young kids behind him. After about twenty kilometers he tied off his skates at the church in Jevnaker and was just in time to hear the priest say "Amen". Mission accomplished: he had seen the priest standing in the pulpit in three different churches.8 How long a mass lasted and whether they all began at the same time is not mentioned of course.

How should we imagine those 'short, thick irons' of Mons Bentsen Toverud? By 'short' was probably meant that the runner was short and did not reach the back of the wooden heel. The first thought therefore goes out to typical Norwegian hook-toed skates, although they actually were totally unsuitable for skating tours and were more suitable for skating figures on a city pond. Much more appropriate for travelling long distances were the longer and lower models, which in Sweden were called skenor. I suspect that they were already in use around 1840, but not by Toverud. Chances are his hook-toed skates were fitted with leather straps.9

Private collection author

HF-06691, not dated, circa1850-1900.

Used in Tingelstad near Brandbu, not far from Randsfjord.

Although as an independent farmer he could probably afford the purchase of a pair of skates from the village blacksmith, we cannot rule out that he had made them himself and tied them with a piece of solidly braided rope. Relatively speaking that was quite a luxury: Hadelanders who did not have a penny to spare often had to settle for a binding of strips of willow bark.10

Figure skating on the rise

Gradually, figure skating gained a foothold in the cities, although on the defective skates of those days it was quite a thing if you could skate outside forwards and backwards and make 'yglor' or a 'Herresving'.11

Illustrerad Idrottsbok - 1888, p. 51

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NMH 992/1875

With thanks to Elisabeth Höier.

Around 1800, artist Johan Tobias Sergel masterfully depicted the falling and scrambling figure skaters in one of his figure studies.

For a long time people in Scandinavia had to rely on foreign publications for instructions on how to skate figures. It was not until 1858 that a booklet appeared in Swedish: a translation and adaptation of the second edition of Art of Skating by Cyclos (pseudonym for George Anderson). It showed that there was a need for methodical examples in the mother tongue.

VinterlandskapYnglingen paa blanke Skøiter Svæver frem i krumme Sving, Vinden om hans Ører fløiter, Men han ændser ingen Ting.12 |

Winter landscapeThe youngster on shiny skates Floats on with curved strokes, The wind whistles around his ears, But he doesn't notice it. |

Evolution in types of skates 1800-1850

In Scandinavian museums only three to four pairs of skates can be found that certainly belong to the period 1800-1850. One pair, rännskor NM.0100140 from 1818, was already discussed in the previous chapter with the long skates.

Based on specific characteristics that these skates show, other skates can also be considered to originate from the first half of the 19th century. Where certain characteristics are very similar to each other, skates are classified as a 'model'.

Full, Mid, Short and Extended

Runners of skates do not always end at the same position under the wooden or metal platform. To describe the various possibilities the following terms are used12a:

ends at the very back

of the heel

ends half-way under the heel

ends in front of the heel

extends beyond

the back of the heel

German hook-toed skate

possibly by Wirths from Remscheid, Germany

Collection Oslo Skøytemuseet

If we may rely on the earliest descriptions of skates in catalogues of Swedish hardware manufacturers, a skate was an article about which there could be no misunderstanding. There was only one unspecified model, which came in different versions: with or without gutter, with or without brass fittings, with or without wooden footstocks even.

Images were not yet included, so we have to guess what they looked like! Presumably, the model was fairly similar to German examples. According to Huitfeldt, an active figure skater from the sixties of the 19th century, even then in Christiania (Oslo) people only used skates with 'Tanger', long upright prows, of German origin.13 No doubt they were all equipped with the clumsy mid- or even short-heel runners and possibly with a single or even double gutter in the bottom of the skate.

|

Features German hook-toed skate with toe guard (OSM): |

|

| Total length: 332 mm | Prow (L x W x H): 42 x 14.5 x 93 mm |

| Foot stock: 290 mm | Runner (L x W x H): 278 x 5.5 x 23 mm |

| Runner without gutter and with extreme curve | Screw connection through protruding heel |

| High hook-toed prow ('tanger') | Brass heel guard may be a later addition.14 |

| Leather toe guard, strung with rope |

Whether Huitfeldt meant imported or copied specimen by 'German origin', he unfortunately left undecided. We can assume that not only the Scandinavian factory blacksmiths, but also numerous local forgers tried to imitate German skates after 1800, although some city dwellers may have turned up their nose for them.

Collection Norsk Folkemuseum NF.1936-0479. Photo: Anne-Lise Reinsfelt

Skate NF.1936-0479 from the collection of Norsk Folkemuseum might be either a replica of a German skate or even a genuine one. Originally the hook toe will have pointed upwards and was probably bent forwards at a later stage.

Blockmühl, Remscheid, 1873

The angle iron at the heel of the skate has an opening through which a screw could be driven into the heel of the shoe or boot. Such an angle iron is known to have been used by German makers.

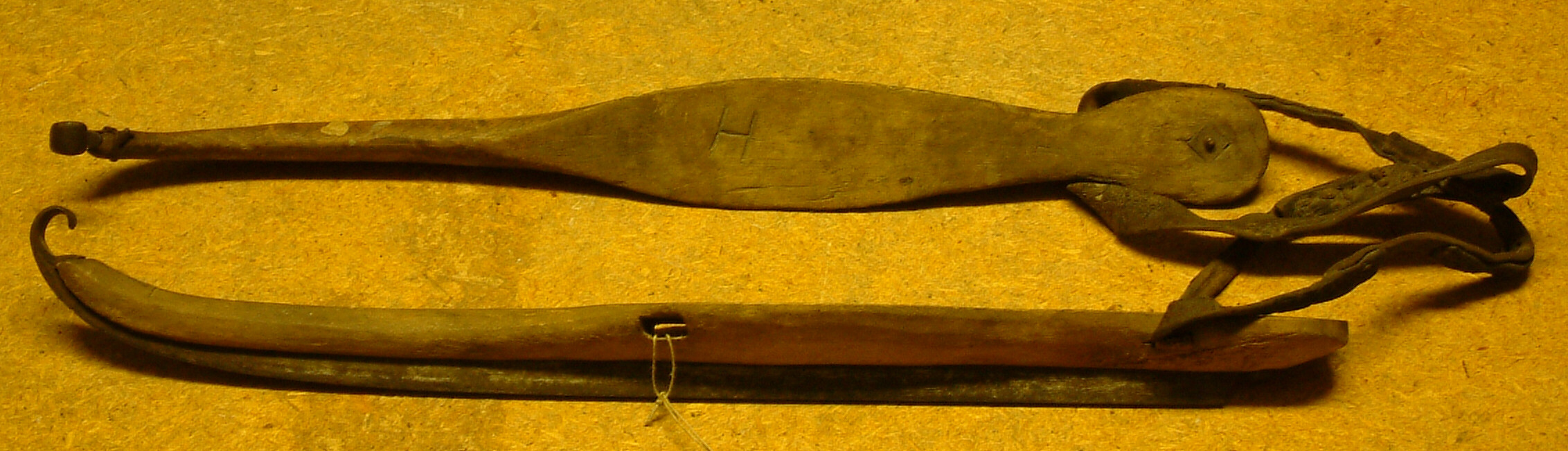

Hook-toed skate with double gutter

Nordiska Museet, Stockholm NM.0094994, detail

and extremely curved blades. Circa 1830.

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm NM.0094994

These small figure skates (NM.0094994) are such a neatly finished product that I suspect we are dealing with a factory skate here. However, marks or stamps are missing and we are therefore not sure whether these children's skates are of Scandinavian origin. The mark 'H' (for höger,right) in the right foot stock indicates use in a Scandinavian country.

| Features NM.0094994: |

| Total length: 235 mm |

| Foot stock (L x W x H): 190 x 57 x 21.5 mm; Prow (L x W x H): 45 x 9 x 56 mm |

| Runner (L x W x H): 192 x 5.5 x 20 mm; The runner ends in front of the heel! |

| Strikingly wide violin-shaped foot stock; Four-pointed screw |

| Double gutter in runners with a lot of curve |

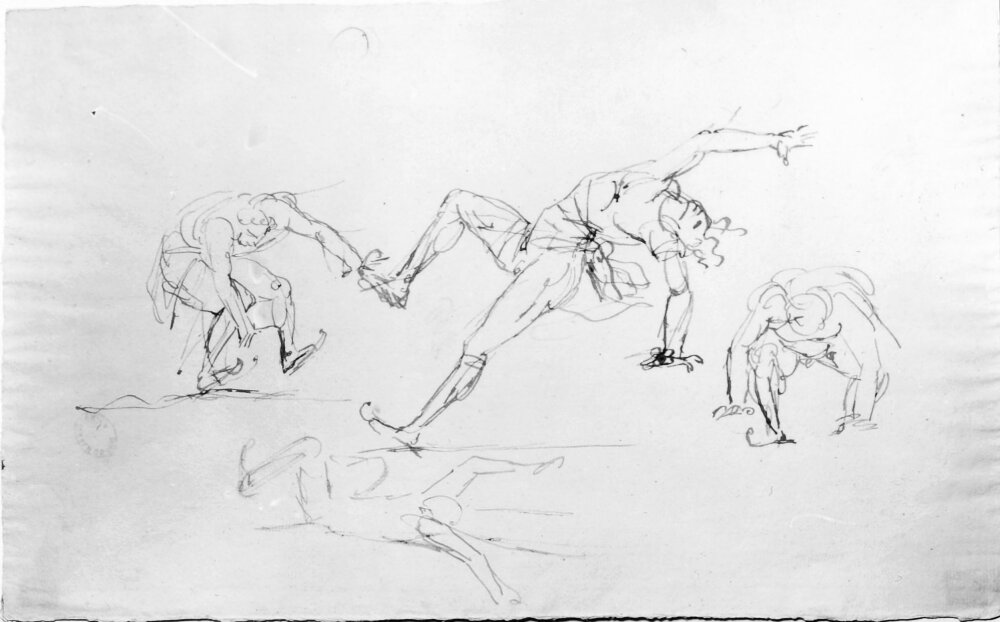

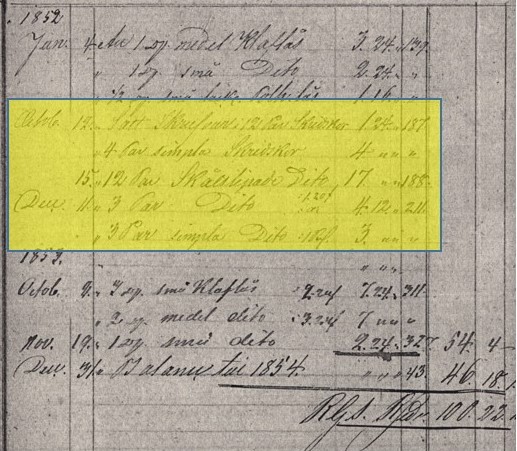

The most striking feature is the rare double gutter, which is fairly easy to place in time. The only references to such a double gutter in a Swedish context are both from the first half of the 19th century. In Dagligt Allehanda of December 10, 1816, a pair of small 'dubbelrandade Skridskor' is offered for sale and they are also mentioned in a price list of the firm Zetterberg, Eskilstuna from 1831.

Source: Jernbolaget / Dir. Christopher Zetterbergs Arkiv, Företagsarkivet (now housed at Arkiv Sörmland), Eskilstuna.

Line 3: Better quality skates with foot stock and fittings / hollow ground with double gutter (dubbelrand)

Of course, this is not to say that these skates actually were made in Zetterberg's firm. The four-pointed screw, quite unique to skates from northern Europe, rather indicates a German origin.

Around 1865 in the Gjesdal southeast of Stavanger (Norway) skates with double gutter could still be delivered to order.

Blekinge hook-toed skate / Kuggebodaskridskor

This pair would have been used by Magnus Månsson uit Hasslö,

who was born in 1845.

Collection Blekinge Museum, Karlskrona. BM19439

Thanks to thorough investigation by Stefan Flöög and Annika Otfors, we have a better than average view of the makers and models from the province of Blekinge in the southeast of Sweden. Flöög, curator at the Blekinge Museum in Karlskrona, describes the typical skates of the region as low, hollowed, usually with a 'spets' (pointed tip) that is often executed in an elegant arc.

Like many Scandinavian skates, they are sometimes marked for left ('V' for vänster or venster) and right ('H' for höger) and occasionally painted brown or grey-green. The binding consists of a combination of leather belts and hemp rope, later also of the wick for petroleum lamps. The filed-out head of the three-pointed screw had to keep the shoe in position on the foot stock.

The prow of the skate usually protrudes just above the foot stock and the gutter covers the full length of the bottom of the runner.15

The most characteristic aspect of the hook-toed skate from Blekinge, however, is the foot stock, with from front to back first the narrowed blunt nose, then a wide, more or less square or rectangular foot plate and finally a rounded bell-shaped heel piece.

This specific combination of shapes (NSB = nose-square-bell) is rare and only known to me from an 1877 Musterbuch by the German skate maker Robert Frohn & Sohn from Remscheid.15a Frohn's model was almost certainly intended for export, but the question is where to.

Work skate

The Blekinge hook-toed skate was generally used on the sea ice of the archipelago (skärgård). Especially when transporting fairly heavy loads on a sledge, such as milk cans or a basket with fish, it was possible to push off well with the deep and sharp gutter.

Collection Blekinge Museum, Karlskrona. BM Nyförvärv

Kuggebodaskridskor, an eroded concept

The skates, which were usually transferred from father to son and therefore almost never appear in inventories upon deaths16 were invariably called kuggebodaskridskor by the local population. The name referred to the skilled blacksmith Pål Johnson and his descendants from the hamlet of Kuggeboda, municipality of Listerby. The names kuggebodajärn and kuggebodaskär also appeared17

Unfortunately, the term 'kuggebodaskridskor' has eroded over the years. For the sake of convenience, the word was also used for skates of other blacksmiths from the area and eventually even for various types of wooden models up to and including factory skates from Eskilstuna.

Such a confusion of concepts does not do justice to the real kuggebodaskridskor. For a clear distinction I use 'Blekinge hook-toed skate' for all skates with the characteristic features of the local model and I reserve the name Kuggebodaskridskor exclusively for Blekinge hook-toed skates made in Kuggeboda.

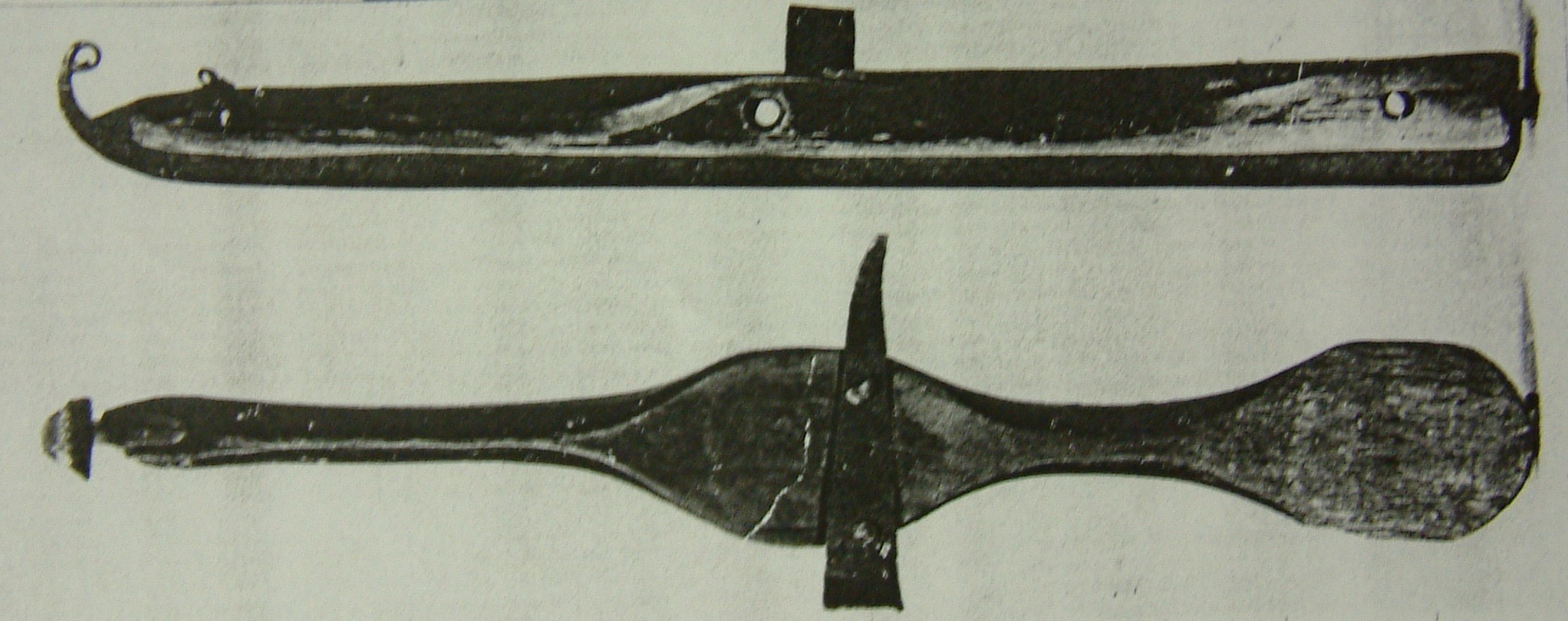

Long all-metal skate

In a century in which iron was used for more and more applications, sooner or later the wooden foot stock also had to go.

Long all-metal skate NM.0028114

Origin: Vik bij Järvsö in Hälsingland (nu Gävleborg)

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm. NM.0028114

| Features of NM.0028114: | |

| Overall length: 570 mm | Prow (L x W x H): 88 x 23 x 85 mm |

| Runner (l x w x h): 559 x 4 x 27 mm | A piece of the runner is missing |

| Foot plate (l x w x h): 465 x 29 x 4 mm | Foot plate has been riveted to the runner |

The skates from Vik, municipality of Järvsö in Hälsingland (NM.0028114) would have been made in the early 1830s. As far as we know, this makes them the oldest all-metal skates from Scandinavia. In the Netherlands, models with a metal foot plate already appeared as from the 17th century, but despite their far-protruding toes, they certainly did not come to a length of 56 cm. The skates from the Järvsö area appear to be the metal equivalent of the long wooden skates from the neighboring provinces of Dalarna and Jämtland, but whether they were used for the same purposes is unclear. The rings, which are forged on top of the footrests, serve as binding holes, so poles for pushing off were probably not necessary. The high curl, which goes around two and a half times and forms a beautiful piece of ornamental ironwork, suggests that these skates were not used for hard labour.

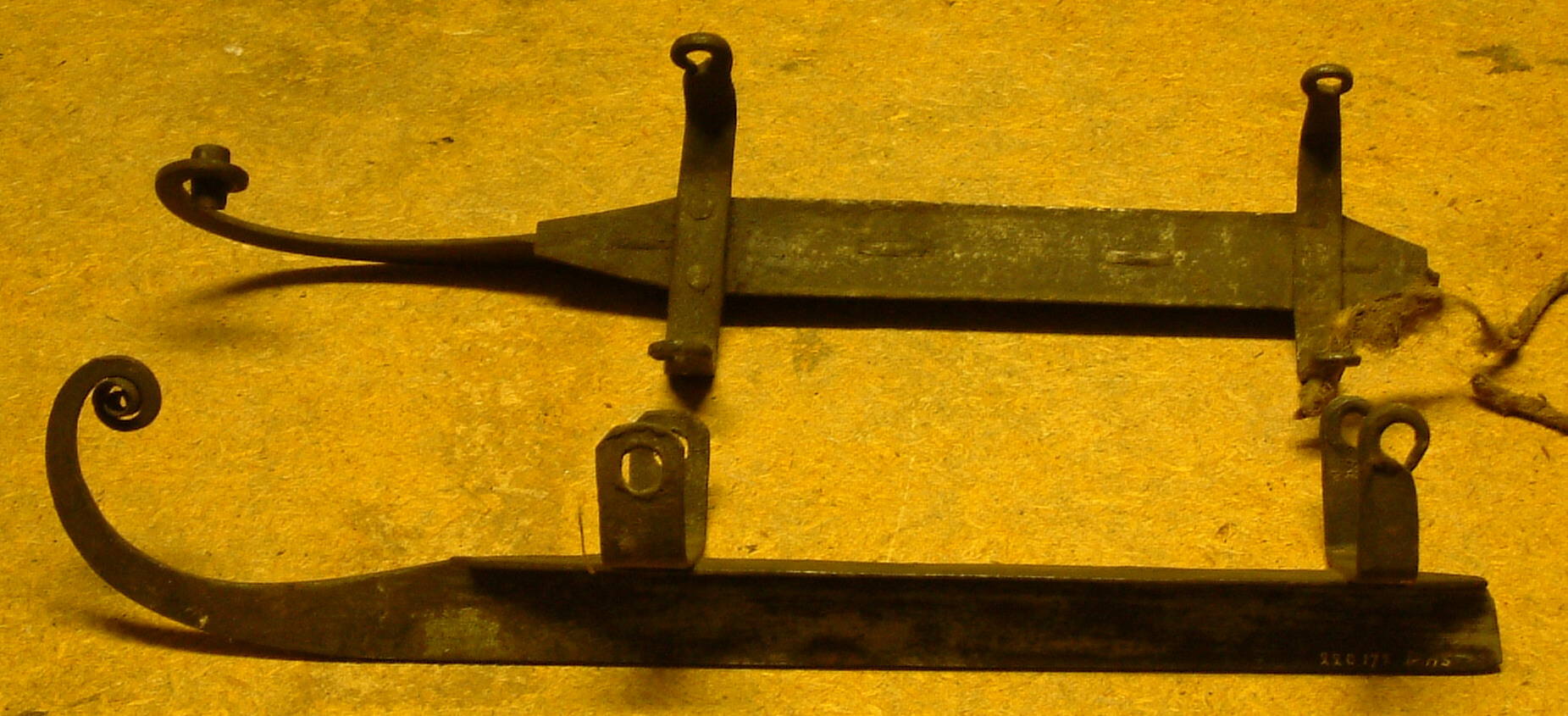

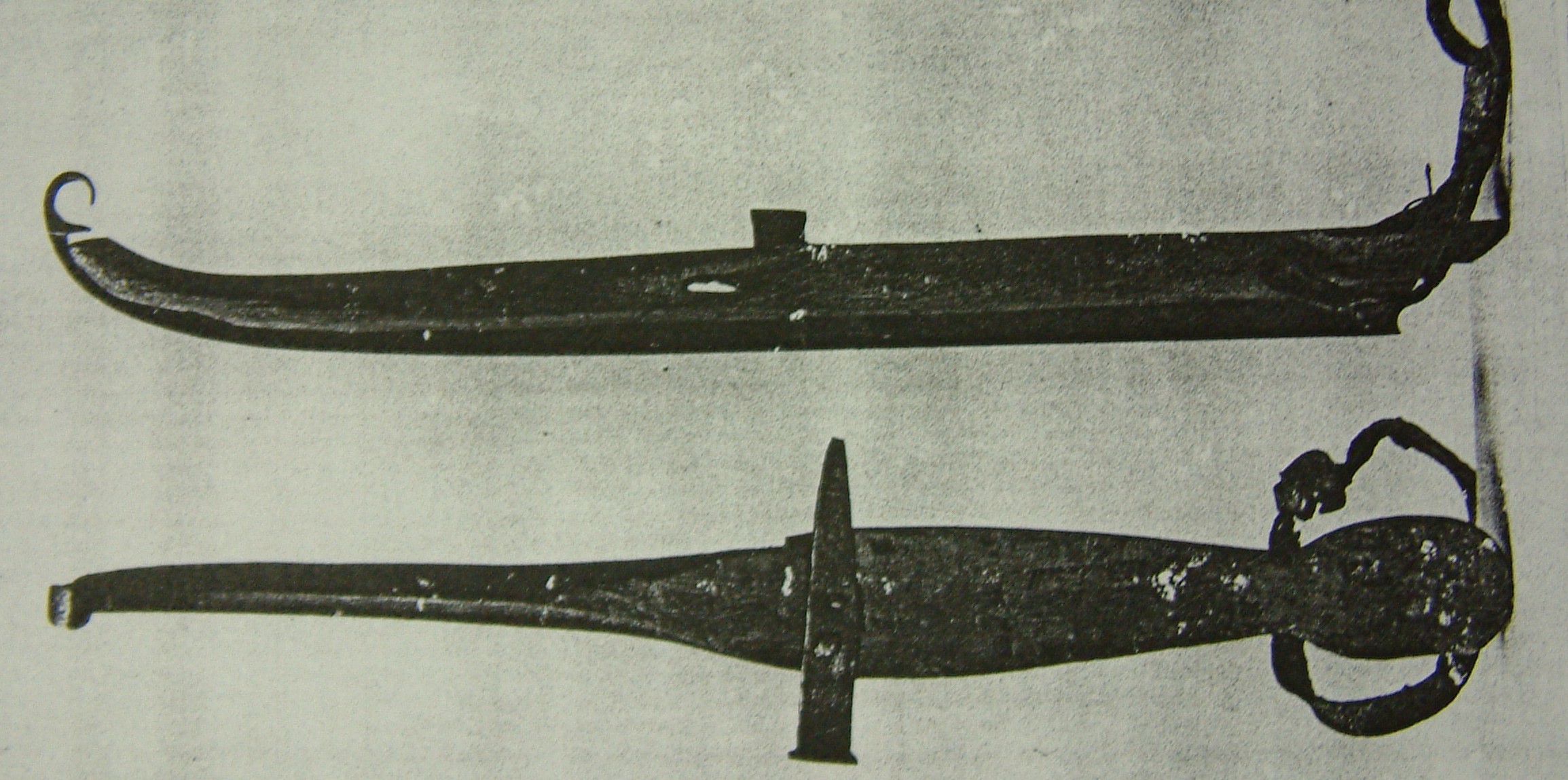

Long all-metal skate: NM.0220172

The curl of a similar, but undated pair, which comes from Föränge, also from the municipality of Järvsö (NM.0220172), even makes three revolutions. Both pairs are probably from the same blacksmith. To achieve his goal, he will have fixed the red-hot tip of the iron on the horn of the anvil and then turned the runner around a number of times with great policy. The prow of the skate is unusually high at 13 cm. In contrast to Western Europe and North America, skates with a prow height of 10 to 15 cm hardly ever occurred at all in Scandinavia.

Not dated; circa 1800-1850

Origin: Föränge near Järvsö in Hälsingland.

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm. NM.0220172

| Features NM.0220172: | |

| T-iron connects foot plate with runner | Runner (L x W x H): 450 x 3.5 x 28.5 mm |

| Foot plate (L x W x H): 313 x 37 x 2 mm | Prow (L x W x H): 130 x 21 x 95 mm |

| Four rings for binding with coarse rope | Extremely high prow for Scandinavian standards |

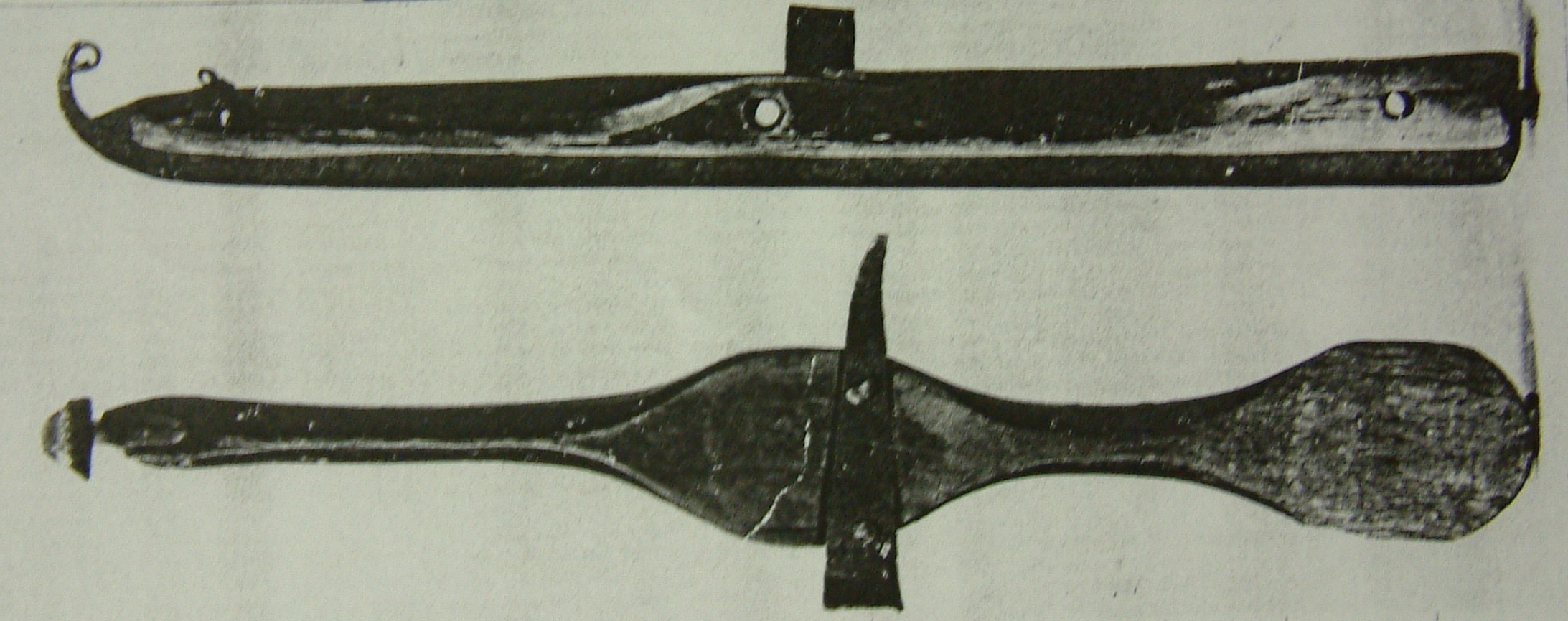

Long wooden toe

and uncovered curl. Length 43 cm.

Not dated; circa 1850.

Origin: Björksön near Hjulsö in Västmanland, Örebro.

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm. NM.0097500

A problem with many old skates is determining their age. According to Nordiska Museet, a number of medium-length specimens with long wooden toes would be from the years 1850-186018 but I suspect that the model was already in use before that time. See below in the frame: The origin of the long wooden toes.

The skates of this type stand out for their long, fragile wooden toes, which make up about two-fifths of the total length of the skate.

They almost all come from the same region, roughly the area between Eskilstuna and Karlstad, and - as if it were a standard size - they are all about the same length and equipped with a low and widely forged curl. Both the forging and the wood carving show a certain craftsmanship.

On a number of characteristics, however, the skates differ slightly from each other, so that a subdivision seems appropriate. I will distinguish between the following submodels:

- long wooden toes with full-heel runners and unclad curls

- long wooden toes with mid-heel runners and half-clad curls

- semi-long toes, fully clad

- Odal skates (Norway)

The last two submodels seem to be of a slightly later period and will be discussed in a following chapter.

Collection Nationalmuseum, Stockholm 17848

Wikimedia Commons

The origin of the long wooden toes

Skates with long wooden toes were already depicted around 1740 by the French painter Nicolas Lancret in a beautiful painting, now owned by the National Museum in Stockholm.19

The work was commissioned by Carl Gustaf Tessin, a Swedish diplomat and art collector. Tessin and his wife were real skating enthusiasts.

This model was also popular in the Netherlands, especially in the Zaan region. Schotel wrote in 1874: 'In the past, the skates were made very long, covered with wood up to the front end, and some skilled skaters still prefer them.'20

The oldest dated Dutch long wooden toes (1834) originate from this area.21

The skate with long wooden toe is both a contemporary as well as a counterpart of the long curled skate with unclad toe.

Around 1765, a remarkable number of 'ordinäre Langhölzer' (ordinary long wooden skates) were manufactured in Remscheid, Germany.22 Although we do not know exactly what they looked like, they probably were the same model. Practically all skates were intended for export, almost certainly for the Dutch, possibly also for the French market as Lancret's painting seems to indicate. Perhaps this model was also exported to Scandinavia.

In short, the long wooden toes are not originally Scandinavian, but were probably introduced in the course of the 18th century by Dutchmen or German trading houses. Over time, blacksmiths in the heart of Sweden adopted the model.

Long wooden toes with full-heel runners and unclad curls (circa 1800-1860)

The two pairs from the municipality of Hjulsjö, NM.0097559 and NM.0097500 are runners with a rather clumsy heel attachment. The wooden toe is low and does not rise upwards. The unclad curl has been quite widely forged. Both pairs are embellished with a small reversed curl on the hook. We have seen this ornamental touch before and this makes an early dating plausible. The double-folded runner at the back, as well as the primitive heel fastening, correspond to the fastening techniques from the period 1750-1800.

Although the runners of both pairs are likely to be from the same forge, the wooden stocks are quite different from each other. NM.0097500 is a bit more sober in design and equipped with a wedge-shaped transverse piece of iron. NM.0097559 has beautifully carved foot and heel plates in the form of coats of arms. On the front 'shield' the recess for a rectangular iron footrest is still visible. Despite the simple and traditional heel fastening, we are dealing with products of skilled blacksmiths here.

Not dated; circa 1800-1850. Length 42 cm.

Origin: Gunnarshult near Hjulsö in Västmanland.

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm. NM.0097559

Photo: Peter Segemark, Nordiska Museet

| Features NM.0097559: | |

| Overall length: 420 mm | Runner (l x b x h): 420 x 5 x 9,5 mm |

| Foot stock (l x b x h): 250 x 50 / 60 x 26 mm | Prow (l x b x h): 170 x 21 x 48 mm |

| Primitive runner with cramp iron in the heel | Beautifully carved footplates in the form of coats of arms |

| Cut-out for rectangular iron footrest | Forged curl |

| Reversed curlet on the hook |

Photo: Peter Segemark, detail

Photo Peter Segemark, detail

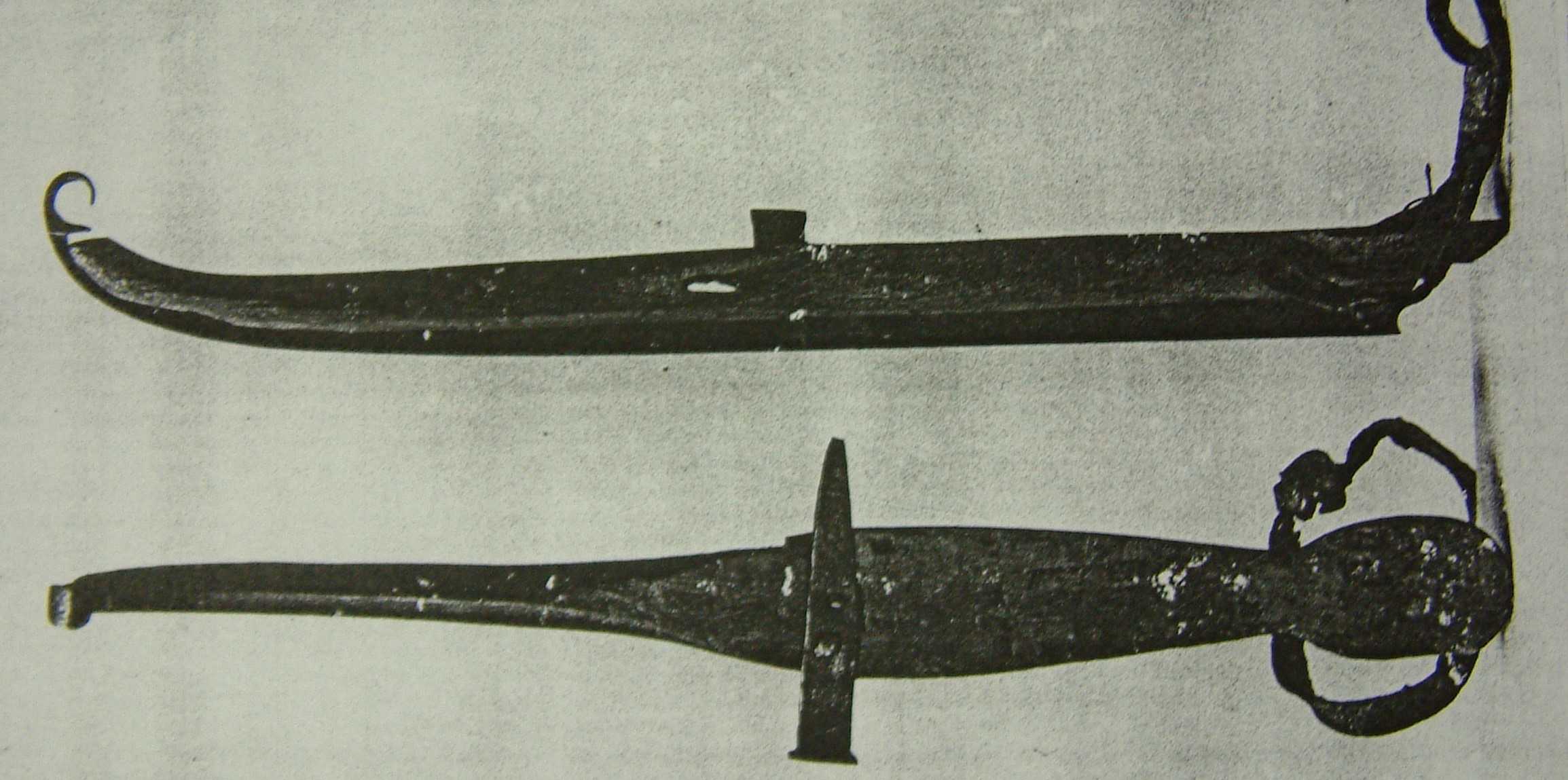

Long wooden toes with mid-heel runners and half-clad curls (circa 1800 - 1860)

Two pairs of graceful and slender skates from the municipality of Bjurtjärn are very similar and are probably from the same maker. With their streamlined foot stocks and runners ending half-way under the heel, but especially because of the long toe, which rises slightly at the narrow curl, they most closely resemble their early Dutch and German counterparts.

Not dated; circa 1850. Length 46 cm.

Origin: Bjurtjärn near Karlskoga in Värmland.

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm. NM.0034335

| Features NM.0034335: | |

| Overall length: 445 + 460 mm | Runner (l x b x h): 420 x 3,5 x 12 mm |

| Foot stock (l x b x h): 290 x 52 x 20 mm | Prow (l x b x h): 155 x 12 x 62 mm |

| Runner ends half-way under the heel | Half-clad toe |

| Traces of brown paint | H for höger (right) in the foot stock |

| Recessed square nut |

With wedge-shaped transverse iron strips at the footstock.

Not dated; circa 1850. Length 45 cm.

Origin: Käxudden (nowadays: Käxsundet),

municipality of Bjurtjärn near Karlskoga in Värmland.

Coll. Nordiska Museet, Stockholm. NM.0040489

Skenor

Pair NM.0040489 from Käxsundet, municipality of Bjurtjärn, which is equipped with a wedge-shaped transverse iron with raised edge, is described as 'skenor = skridskor att bruka på långresor'19, skates for use of long distances, for example for visiting family, the market or for commuting between home and work.

The word skenor literally means runners or rods. Two hundred kilometers further north, in the vicinity of Älvdalen, skates with half-long toes without curls were also called 'skenor'. This name therefore appears to be unsuitable for indicating a certain type of skate; at most, we can use it as a collective term for skates that were used to cover considerable distances.

with mid-heel runner; no curl

Not dated; circa 1880-1920.

Origin: Gävle/Gefle

Collection Länsmuseet Gävleborg

XLM.07535

Skate makers 1800-1850

With the majority of the skates covered above, we unfortunately have no data about the makers behind them. The opposite also occurs: it is known from literature that skates were made in certain workshops, but we do not always know which model they were. This is particularly true of some skate makers from Eskilstuna, the central Swedish town that I will take as an example - and not without reason as we will see - for the development of the craft industry during this period. In order to better understand the activities of the skate makers there, I will first sketch a general picture.

The craft industry in Eskilstuna

Archive Jernmanufaktur (Jernbolaget)

Företagsarkivet (now Arkiv Sormland), Eskilstuna

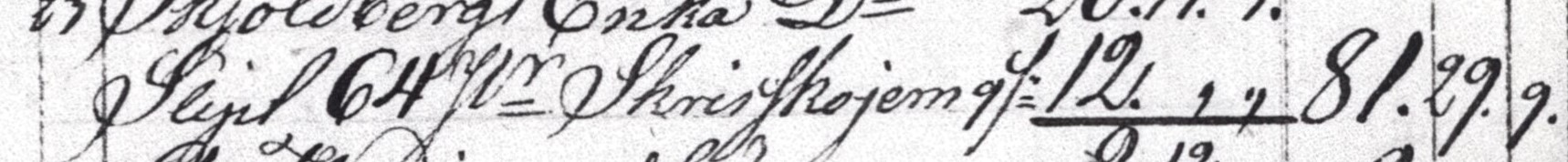

Post June 22, 1811: Slipat 45 pår Skridskor

On June 22, 1811, the cash book of grinder C. Setterberg (Zetterberg) in Eskilstuna shows an entry of 45 pairs of skates. Forty-five pairs, in June! Although it is the oldest reference to the manufacture of Scandinavian skates that I have come across, the number of pairs and the date show that there must have been a whole history underlying it.

At the time apparently there already was a carefully designed production process, in which people worked ahead of the winter season and most likely not exclusively for the local market. It could very well be that this batch of skates was destined for hardware stores in Stockholm. In those days, goods were transported from Eskilstuna by horse and cart to Torshälla and from there by sailboat across Lake Mälaren to the capital. At least as long as possible, because in late autumn and winter there was a good chance that ships would get stuck in the ice. Therefore it was only logical to prepare skates in time for shipment and that is why they ended up at the grinder, on whose role we will come back later, early in the summer.

Of course, such a set-up with well-considered planning did not just appear out of the blue and must have developed at a much earlier stage. Therefore it is not so bold to assume that skates were already made in Eskilstuna, the handicraft city that would grow into a kind of Remscheid of Sweden as far as skating is concerned, before 1800.

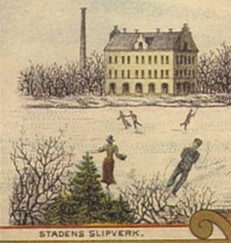

Running water

In the first half of the 19th century radical changes took place to the tjänsteverken where blacksmiths and manufacturers could crush and sharpen ironware. From 1804, the old grinding houses had to make way for a new complex with a larger capacity, including a grinding house for fine processing. Christopher Zetterberg, the grinder who so carefully recorded the job of those 45 pairs of skate irons in 1811, often made use of it. As for many other articles, fixed rates also applied to the grinding and polishing of skates, as evidenced by a price list for grinding and rolling work from 1837, on which both skenor (here in the sense of rods?) and skridskor are mentioned.20

Cover of Dahlgren catalogue, detail

Also the old knipphammare were gradually replaced, so that eventually (around 1850) there were four of them, one for blacksmiths working from home, one for the scythe smiths, a third for various products and the coarser work, and finally the fourth, which was also exclusively intended for the scythe smiths.

All these buildings, just like the Gevärsfaktori (rifle factory, A.D. 1813), stood on the edge of the river Eskilstuna and the machines were of course powered by the force of running water. That also made them vulnerable. With an abundance of water in spring, the blades had to be taken out of operation. In other seasons, when the water supply was low due to drought or frost, the rifle factory was the first to have a right to water and the blades of the tjänsteverken and as a consequence also the crushing and grinding came to a standstill. If these conditions lasted a little longer, then of course the activities of blacksmiths and craftsmen also stagnated.21

Because of the dangerous current, it was forbidden to skate on the frozen Eskilstuna, but young apprentices sometimes did not care a bit when the river was frozen over and they were out of work.22

Forging by hand

Ironware was created manually in the small forges and workshops of Eskilstuna. Apart from the use of the grinding houses perhaps, the working method was still completely similar to that of the average village blacksmith elsewhere in the country. In contrast to a certain degree of specialization, there was hardly any division of labour (in which several craftsmen take turns working on a part of the final product). According to Johan Svengren, who came to Eskilstuna in 1836 as an office clerk and would later become the first director of the Eskilstuna Jernmanufaktur, all forgings were then made 'under hand' and in an old-fashioned way. This of course gave the products their own character and that was exactly what the consumer asked for.23

Oil painting by Olof Hermelin, 1887. Collection Eskilstuna Stadsmuseum 17055.

Source: Carl Gustafs Stad - 1959, p. 104

Bona fide blacksmiths initially marked their articles with their own stamp and at the Fristadskontoret also with the letters 'EFS', for Eskilstuna Fri Stad.24 After the Fristad had to give up its exclusive rights in 1833, legal protection on trademarks would be lacking for some fifty years.25

I am afraid that no Fristad skates from before 1833 have been preserved, because as far as I know the stamp 'EFS' does not occur on any specimen. It is possible that skates have been put into circulation via clandestine trade (side jobbing) by apprentices and journeymen. They sold their rogue forgings - often of inferior quality - unstamped and below the fixed price, which of course was a thorn in the flesh of the authorities and the förläggare.26

Over time more and more large workshops were built in the former Fristad where division of labour was gradually applied. They were the forerunners of the real factories, which would follow a few decades later.

Hardpressed blacksmiths

The sale of forgings was usually done through the so-called förläggare. Such a förläggare had the local blacksmiths almost literally in his power. He supplied them with wrought iron, gave them tools on loan and rented out the small workshops and houses, in which the blacksmiths lived together with their workers and their families. In practice, the förläggare often also had a monopoly on their end products, which he resold himself.27 Although the förläggare system was officially abolished when the Fristad was introduced in 1771, not much had come of it in practice. This was mainly due to the weak financial position of the blacksmiths, which also resulted in a fairly extensive barter trade.

Generally a small self-employed craftsman could not afford a smidesbetjänte, a salesman who tried to conclude orders for his employer, usually a förläggare, all over the country.

Finally, in the absence of a direct shipping connection to the capital, the small independent blacksmiths were normally not able to go to Stockholm to sell their goods directly to ironmongers. To this end, the goods first had to be transported on foot or by horse and cart to Torshälla near Lake Mälaren, after which one was dependent on a very irregular transport by sailing ship. All in all, it could take two weeks and that was obviously not feasible for the small entrepreneur.

It went the other way around. During a number of winters in the 40s and 50s of the 19th century, wholesaler C.J. Bergman came by sledge from Stockholm to Eskilstuna with two armed guards and a suitcase full of cash. The craftsmen, who were apparently aware of his arrival in advance and therefore had a lot of goods in stock, received more from him for their products than from a förläggare or broker. So much was sold that Bergman was eventually able to return home with about twenty to thirty fully packed sleds.28 The convoy followed the fixed ice roads, which have always run over Lake Mälaren since the days when the Vikings moved to the market place Birka.29

It was not until around 1860 that a direct (steam) shipping connection with Torshälla became possible via the newly constructed canal.30

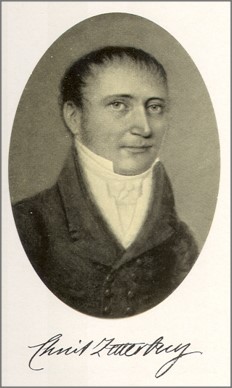

Christopher Zetterberg, Eskilstuna, active 1810-1852

Bron: Eskilstuna Jernmanufaktur Aktiebolag 1868-1943, p. 9

Christopher Zetterberg was born in 1775 in Riala in Roslagen (north of Stockholm). This region was traditionally a center of metalworking, where especially the town of Wira was known for its production of swords. After the establishment of the Fristad in 1771 many blacksmiths and workers from the area moved to Eskilstuna. Also Zetterberg was apprenticed there at the age of 15 to grinding master Moberg from the old town. After he had become a journeyman - the old guilds had apparently not yet been completely dissolved - he visited Solingen and Remscheid in Germany around 1800 to gain knowledge.31 For this journey, he received an advance from a benefactor who had taken an interest in this progressive young man. Zetterberg, who was very eager to learn, kept an Anotatsions Boch (notebook), in which he described the different production methods for all kinds of work. A closer look at this book, which has fortunately been preserved, may show whether he visited workshops there that manufactured skates, and if so, to what extent he was influenced by those German skate makers.

Upon his return, Zetterberg first started as a grinder in Tunafors, as Eskilstuna was still called at the time, and from 1807 he established himself as a grinder and maker of forgings in the Fristad. In his own workshop, tools, locks, cutting knives and swords were made.

From his notes (arbets annotatjoner), which he continued in 1810, it appears that he did not shy away from the application of new methods and materials and had an eye for the economic side of business operations. Yet, from those same notes it is also clear that the old handicrafts still played a major role, even in a large workshop like his. His most important products even continued to be manufactured manually. However, he had had a certain degree of division of labour introduced, which led to greater specialization for individual employees.32

Förläggare Zetterberg

In 1811, after he married the widow Jeanette Sundin, who had inherited one of the largest hardware stores in the city from her late husband, Zetterberg quickly grew into one of the most powerful förläggare of Eskilstuna. He resold the end products of the blacksmiths tied to him.33 Even many of them who were independent, but suffered from a chronic lack of cash, especially in winter, exchanged their forgings with him for food. In spring, when the ice had disappeared from Lake Mälaren, Zetterberg had all wares loaded onto a barge, sailed with it to Stockholm and sold everything to the hardware stores.34

Grinding gutters in other people's skates?

It is precisely the wide variety of roles (grinder, head of his own workshop and eventually förläggare) that makes it difficult to determine whether Zetterberg also made skates himself.

The first time he is associated with it was as a grinder in 1811, as we have already seen. But how should we interpret that entry of 45 pairs of skates dated June 22 in the cash book of 'slipern C. Setterberg'?35 Concluding from comparison with price lists from later years, it probably concerned a batch of common hook-toed skates. However, we do not know whether they were made in his own workshop or were offered up for grinding by some independent blacksmith. Zetterberg probably was not yet a förläggare of any significance in the year of his marriage, so we can practically rule out the chance that the skates came from the workshop of dependent blacksmiths, as may have been the case later.

The cash book also shows that Zetterberg already rented the grinding house fairly regularly at the time and had thus quickly established his reputation as a grinder. But what was the nature of that grinding work on that 22nd of June? Can we conclude from the description '45 pairs of skates' that it was a finished product? And on the other hand did 'Sharpened 64 JV skate iron'36, an entry on December 21, 1811, concern 64 loose runners?

The amount of money involved in December turned out to be much higher than in June, especially when reducing it to an average price per pair (6.5 :18 skilling37). Those 18 skillings correspond to the additional price that was paid twenty years later for a pair of skates with a single gutter. If my assumption is correct, in December the work probably concerned applying gutters in loose runners, from which follows that in June it may have been about finishing off ready-made products, such as polishing, for example.

That Zetterberg - more than sixty years after the technique was started in Remscheid - was the first Swede who could grind a gutter in skate irons, seems unlikely. But if that were the case, he must have acquired this skill almost certainly during his visit as a journeyman over there.38

In 1831 - the year in which skates are mentioned in his price list - Christopher Zetterberg had grown into a wealthy man who was highly regarded. In 1817-18 he had already been elected riksdagsman (member of parliament). Although he continued to live in the old town, he had an office building built in the Fristad around 1825.39

Photo circa 1940, Eskilstuna Jernmanufaktur Aktiebolag 1868-1943, p. 31

Although he was registered as a klingsmed (sword maker) in Eskilstuna, a whole range of products were manufactured in his workshop.

Zetterberg also owned real estate, but above all was a powerful förläggare. Although his income from the sale of goods from blacksmiths tied to him (smidesförsäljning) showed a sensitive dip in 1831, it still turned out to be three times as high as the income from the sale of products from his own factory. In addition, he also bought goods from independent blacksmiths, and then resold them. In total, Zetterberg had to deal with no less than 73 blacksmiths who delivered to him. About half of all forgings went to wholesalers and retailers in Stockholm. Only 5 % was sold locally.40 Whether that ratio also applied to skates is unknown.

In the price list from 1831, both Zetterberg's own and other people's products are included41 and therefore we are still not sure whether the Zetterberg company made skates in its own workshop.

From the Priscourant we can conclude that there was probably only one type of ordinary skates (presumably the hook-toed skate), which could be supplied in different versions:

| Line 1 |

Skridskor: per par ord. Skates: per pair ordinary (quality) |

36 s. 36 skilling |

skålsl. hollow ground |

1 Rd 6 Sk. = 54 Skilling |

| Line 2 |

med Träd d:o with foot stock ditto (= ordinary) |

42 s. 42 skilling |

d:o ditto (= hollow ground) |

1 Rd 12 Sk = 60 Skilling |

| Line 3 |

bättre d:o och beslag better (quality) with wooden foot stock and fittings |

2 Riksdaler = 96 Skilling |

d:o dubbelrand ditto (= hollow ground) with double gutter |

2 Rd 28 Sk = 124 Skilling |

The difference between regular skates and regular skates med Träd is not entirely clear to me. Presumably, ordinary skates were also delivered without foot stocks, although - given the price difference of only 6 Skilling - that hardly seems conceivable. It would mean that the foot stock only made up 1/7 of the price. Did some people prefer to make their own foot stocks or were they produced elsewhere?

The hollow ground models fit in perfectly with the frame of the time. What is striking is that the additional cost for a gutter is about 50 % higher than the price of regular skates! Those figures correspond with the situation in Remscheid around 1800.

The double gutter (dubbelrand) has been dealt with in Evolution in type of skates 1800-1850. A link between the double-edged children's figure skates NM.0094994 and the Zetterberg company has not been proven.

The improved version, presumably with brass fittings, was more than twice as expensive as the ordinary one without fittings and therefore a real luxury product. This was even more true for a similar pair with double gutter. Probably this version was also made with a better quality steel. Nothing is mentioned about the binding. One probably had to go to the saddler for straps.

The inclusion of a luxury model proves once again that enthusiasts from well-to-do circles also liked to go skating.

Collection Armémuseum, Stockholm AM.049990

The items concern trader C.A. Lang from Eskilstuna.

Source: Företags Arkiv, Dir. Johan Svengrens Arkiv, G II d 1.

The last few years

In 1851 Zetterberg participated in the Great Exhibition. During this first World Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London, he showed specimens of sabers and swords. Skates were not to be seen in his stand; they were exhibited exclusively by German and English firms.42

In 1852, the year of Christopher Zetterberg's death, the company employed some 50 to 60 employees, including two bookkeepers, two shop assistants and three smideshandelsbetjänter (commercial travelers).

After Munktell's mechanical workshop and the rifle factory, Zetterberg was the largest employer in the city.

After his death, the company was taken over by his accountant Johan Svengren, who would develop it into the mighty Eskilstuna Jernmanufaktur AB, which we will encounter later.43

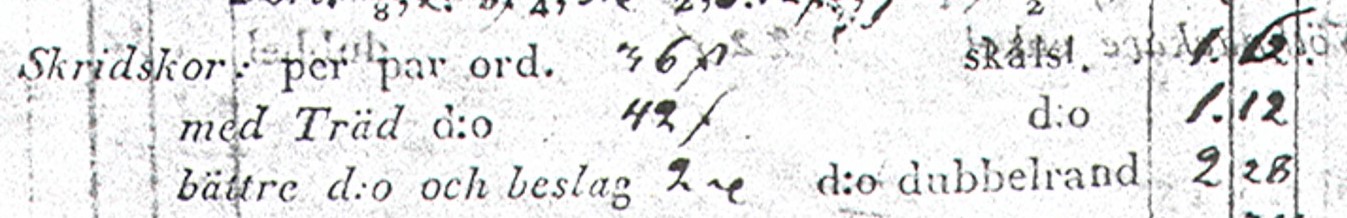

In Svengrens account books for the year 1852 there are a number of entries that concern skates; from them we can conclude that still the same models were used as in 1831. Prices had risen by more than 14 %.44

| Date | Description | Amount in Riksdaler + Skilling |

| 12 Oct. |

Screws placed in 12 pairs of skates |

1 Rd 24 Sk (= 72 Skilling) |

| 4 pairs of ordinary skates | 4 Rd (= 192 Skilling) | |

| 15 Oct. | 12 pairs of hollow ground skates at 1.20 | 17 Rd (= 816 Skilling) |

| 11 Dec. | 3 pairs of hollow ground skates | 4 Rd 12 Sk (= 214 Skilling) |

| 3 pairs of ordinary skates at 1.00 | 3 Rd (= 144 Skilling) |

Conclusion

Although it is unclear whether skates were made in Zetterberg's workshop itself or were supplied by other blacksmiths, whether independent or not, we can assume that Zetterberg in his dual role as both employer and wholesaler actually decided the range and size of the production for about forty years. Further archival research may provide a more complete picture of the production of skates by or for Zetterberg.

Although Johan Svengren, Zetterberg's accountant and successor, established the Eskilstuna Jernmanufaktur AB in 1863, Christopher Zetterberg can be regarded as its founding father.

Anders Magnus Zander, Eskilstuna, circa 1850

Christopher Zetterberg was the largest, but certainly not the only entrepreneur in Eskilstuna who had skates made and traded them around 1850.

Anders Magnus Zander, who was born in the Fristad in 1825, was known as the 'coffee grinder blacksmith', because of the designs he made himself for that article.

Knives, however, were his most important product. At the age of thirty he already employed about 20 workers (a journeyman and the rest apprentices). In addition to the main product, they manufactured scissors, forks, locks, candlesticks and weighing hooks, among other things. Also the manufacture of skates, which assumably did not differ from what was customary, Zander probably left to his workers.

Rod iron, which he ordered from an ironmonger in Västerås, was delivered three to four times a year via steamboat and carter. He obtained steel from Zetterberg.

Zander had more outstanding claims than debts and he was not really dependent on the förläggare with which he traded.

Zander also spread his risk in terms of sales and made use of various sales channels. He sold on order for example to traders in Stockholm and Eskilstuna, including Zetterberg and his successor Svengren. Therefore it is conceivable that the skates that Zetterberg sold around 1850, were made at Zander’s workshop, but that is purely hypothetical.

Zander had his own representatives in various cities and also business travelers, the so-called smidesbetjänter, who travelled through Sweden with samples of goods on his behalf. In inns and at local markets in various provinces - for which they had to apply for new travel passes again and again - they tried to conclude orders. If successful, the order was sent by post to Zander in Eskilstuna, who then sent the goods, often in fairly small batches. Although it was a risky and fraud-prone system, this network of business travelers even reached as far as Christiania (now Oslo, Norway). Zander himself also appeared at markets in the wider area of Eskilstuna. Although we should not completely rule out that he sold skates via this route, this is not apparent from his notes (promemorier för marknader).44 Perhaps skates were too difficult an article to sell this way (different sizes) and also were not specialized enough (any village blacksmith could make them).

On March 30, 1852, Zander announced that he had learned that many traders in Eskilstuna profit by buying forged goods from my workers (for a good price), which have been stolen from me and bear my mark. He makes it clear that from now on he will no longer let this illegal trade go unpunished.45

It is not very likely that this fraud concerned his skates, which all in all form an even greater mystery than those of Zetterberg. In fact, I have not even been able to find a Zander knife or coffee grinder in the collections of Swedish museums, let alone a pair of his skates.

No real skate makers

Actually we cannot call entrepreneurs like Zetterberg and Zander real skate makers. Although they both started as blacksmiths, they gradually developed into merchants, who left the dirty work to others. The real maker of ice skates in Eskilstuna was probably an apprentice or journeyman working for a blacksmith, or at most a small independent blacksmith himself. In any case, they were individuals whose personal histories remain as dark as the grey forge in which they worked. All in all, there must have been a lot of them, because the small craft industry was not just limited to Eskilstuna of course.

Pål Johnsson (Sme-Pålle), Kuggeboda, 1830-1880

By way of exception and thanks to thorough research by Stefan Flöög (Blekinge Museum), we can get to know some of Zander's and Zetterberg's contemporaries who did make skates with their own hands and even managed to create a certain reputation.

Kuggebodaskridskor

Kuggebodaskridskor are identical in model to the Blekinge hook-toed skate. Their name refers to the village of Kuggeboda in Listerby Municipality, Blekinge County, on the east coast of southern Sweden. They were once a household name and were held for the best and fastest skates in the area.

Pål Johnsson (1810 -1883), born and raised in Kuggeboda, is considered to be the founder of this skate, that did not get his name, but that of the village. It is not impossible that his father, as an independent farmer and peasant smith, or even his grandfather, who was a master blacksmith at a gun factory in Ronneby, also made them.

According to a newspaper article, skates made by 'Smepållen', as he was called, were still present in the forge of his grandson Herbert Åkesson in 1964, but have not been preserved.46 We therefore do not know whether Pål Johnsson, like his descendants Johan and Herbert Åkesson, stamped his own mark in both the inside and outside of the prow of his skates.

The real kuggeboda skate radiated a certain elegance, but owed its reputation mainly to the quality of the product. One Viktor from Vettekulla even claimed that a coin of two crowns was merged with the steel of the skates.47 That assertion may not be true, but it does indicate that Sme-Pålle and his successors apparently knew how to well steel to the runner, how to harden the whole thing and how to grind a gutter in it.48

Collection Blekinge Museum BM.13745

As a farmer on poor soil, Pål grew rye, oats and potatoes. He also earned money on the side, not only as a blacksmith, as was the custom in the family, but also as a fisherman. Since he was called 'Sme-Pålle' by everyone, we can assume that working in the smithy was not his most insignificant occupation.

It seems that he could use the extra income from the manufacture of skates and tools, although as the owner of some plots he was not really poor. He owned his own horse for example, as well as cows, some small cattle and simple agricultural tools. The possession of a plough, however, he had to share with someone else.

Perhaps once in a while a seabird was shot down, for his property included both a rifle and a pistol.

For catching fish, of which a tenth part went to the pastor in Listerby according to a parish decree of 1854, Pål had a rowing boat, nets and other fishing equipment. The eel spear from his forge is part of the logo of the Blekinge Museum.

Finally, there was a smithy made of wood with the usual tools, where he made horseshoes, eel spears and skates.

Already during his lifetime Pål Johnsson was described as the 'widely renowned maker of the so-called kuggeboda skates', which owed their legendary properties to the steeled and hollow ground runner. They were not only used by fishermen, who in winter searched the wide expanses of ice with their eel spears in hand, but also for making trips on the ice from the skärgård (archipelago) to Karlskrona.

In the absence of a son who could take over from him, in 1876, about four years before his death, Jonsson had the smithy transferred to his then 14-year-old grandson, Johan Åkesson.

In his time 'Sme-Pålle' was actually not the only smith in Blekinge who made skates ...

Anders Petterson, Slätten, circa 1840-1885

circa 1840-1850

l x b x h: 310 x 60 x 45 mm

Collection Blekinge Museum, BM 13793

According to the intake data of the Blekinge Museum, the pair of Blekinge hook-toed skates BM13793 would have been made in the early 19th century by 'Anders på Slätten'. Slätten is a common place name in Sweden, but in this case probably the hamlet of Slätten or Slättenäs is meant, situated in the parish of Förkärla, just east of Listerby in the province of Blekinge. According to the husförhörslängderna (a kind of church register), a certain Anders Pettersson was born there in 1821 and after some wanderings he worked as a sockensmed (local parish smith) in Förkärla until his death. It seems very plausible that he was 'Anders på Slätten' and given his date of birth, the pair of skates BM 13793 will be from around 1840 at the earliest.

Life course of BM 13793

At the time the skates, which are described as 'trälöpare' (literally: wooden runners), were ordered from Anders by Johannes Jonasson from Bökenäs. In 1875 they came into the hands of his brother's son, Johan Svensson, shoemaker in Hjortaham. In 1920, watchman Albert Hammarström bought them at an auction. Finally, in 1958, they were donated to the Blekinge Länsmuseum.49

It seems that blacksmithing ran in the blood of the Pettersson family, for Anders' father, Petter Persson, also was 'sockensmed' in Förkärla. However, since he died when the boy was only eight, Anders could not have learned the trade from him. Anders' brother Sven, who was six years older, also became a blacksmith.

In January 1867 Anders, who lost his wife in 1865, was sentenced by the court in Ronneby to a hefty fine of 50 Riksdaler for public drunkenness.

He continued to practise his profession in the same smithy until his death in 1885.50

Anonymous skate maker from Stjärnsund near Hedemora,1800-1850

Skates were also made in the bruk in Stjärnsund northeast of Hedemora, about 100 kilometers north of Eskilstuna.51 It is not known whether the stamp for hardware from Stjärnsund was also used for skates.

Candidate skatemaker from Hjulsö or surroundings, 1800-1850

The blades of both skates with long toes and full-heel runners, which have been brought in from the surroundings of Hjulsö, could have been manufactured in the vicinity by the same skate maker.

It concerns the skates NM.0097500 and NM.0097559 from the chapter Evolution in types of skates 1800-1850.

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm

Candidate skate maker from Bjurtjärn or surroundings, 1800-1860

Both skates with long toes and mid-heel runners from the vicinity of Bjurtjärn, could have been made there or in the nearby surroundings by the same skate maker.

These are the skates NM.0034335 and NM.0040489 from the chapter Evolution in types of skates 1800-1850.

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm

Anonymous skate maker from Wira Bruk, 1820-1850?

probably from a later period.

Collection Upplandmuseum UM17604

Skates were probably also made in Wira Bruk (Roslagen, just north-east of Stockholm), once famous for the quality of its swords and later known for scythes and axes

Roughly until the middle of the 19th century, the owner of Wira Bruk acted as förläggare, who provided the blacksmiths in his service with materials and compensations for the forgings supplied. After that time, the blacksmiths rented their workshop from the owner and sold their products themselves, partly to ironmongers from Stockholm and Norrtälje, among others, and partly to farmers and other local residents who came to Wira to buy new tools. Farmers and villagers from the surrounding parishes as well as islanders from the skärgård (archipelago) often combined a visit to the grain mills in Wira with a visit to the forges to complement their supply of scythes, axes and other utensils. Or had broken tools repaired and blunted axe tips re-steeled.52 Most likely, this also applied for skates, but I have not been able to find hard evidence for it, in the form of the WIRA53 stamp, for example.

On skates to Wira Bruk

Johan Erik Nordlund of Möja was a man’s man on the ice. One winter day he skated from Möja to the nearby island of Norrö to fell a fathom of wood. By the evening he damaged his axe, strapped on his skates and found his way across the sea ice to the mainland in the moonlight. Once there, it was still about half an hour on foot to Wira Bruk - the centuries-old ironworks where he once might have bought his skates - to have his axe repaired. He spent the night ashore, skated the more than twenty kilometers long route back to Norrö the next day, chopped another half a fathom of wood and set course for Möja again.54

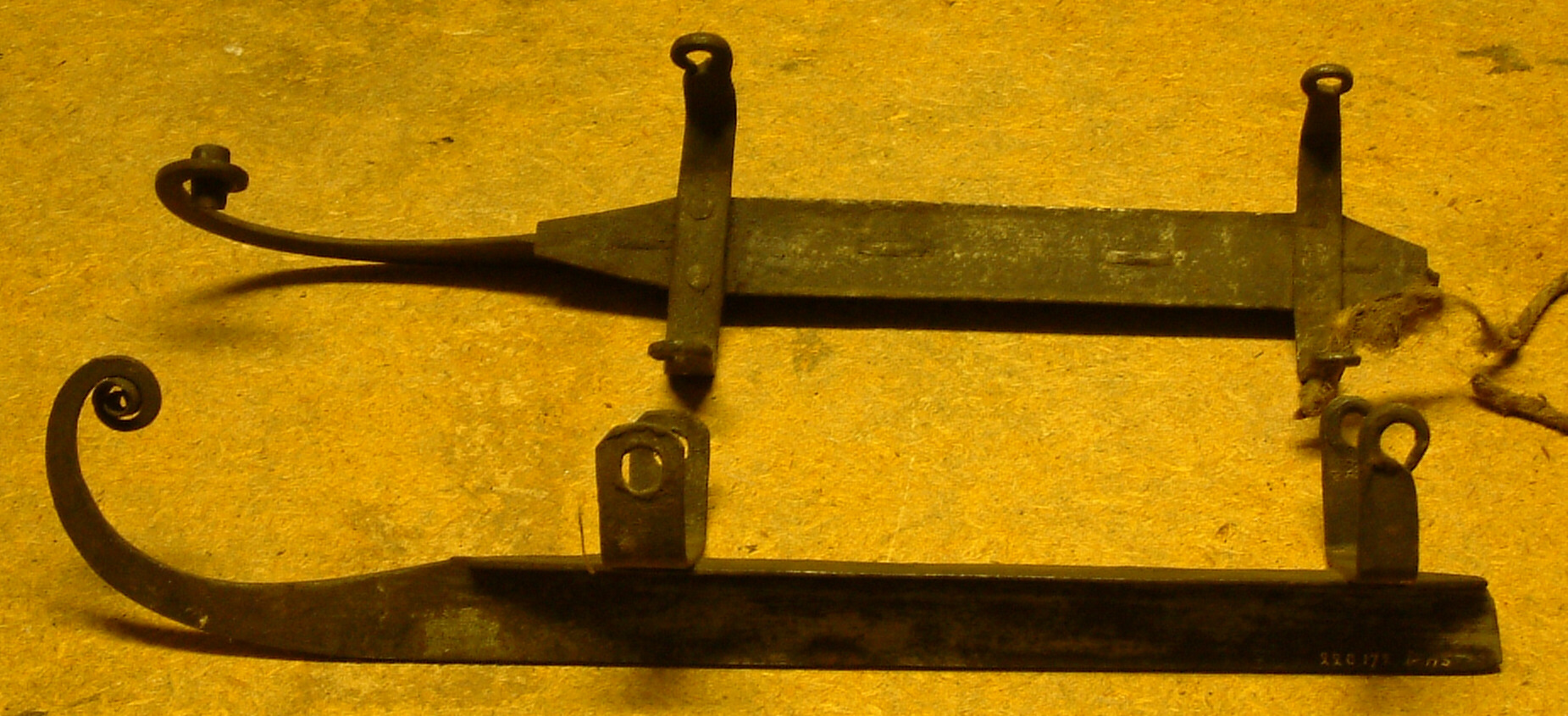

Candidate skate maker from Järvsö or surroundings, circa 1830-1840

Both pairs of all-metal skates from the municipality of Järvsö were probably made there or in the vicinity by the same blacksmith.

These are the skates NM.0028114 and NM.0220172 from the chapter Evolution in types of skates 1800-1850.

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm

Collection Nordiska Museet, Stockholm

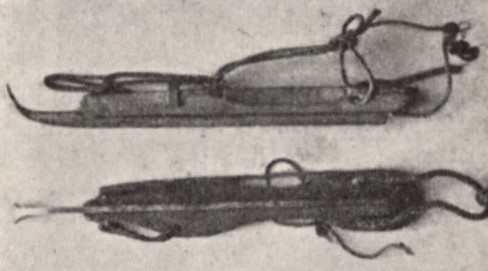

Anonymous skate maker from Svene, Numedal, circa 1845

Source: Festskrift - 1920, p. 341 ill. 4

The Norwegian Skating Museum in Oslo once owned a pair of skates with steeled runners of an unknown blacksmith from Svene in the Numedal north of Kongsberg.