From Nobility to Commoners on Ice!

Author Wiebe Blauw, 2001

Translation Cheryl Richardson, 2019

Nobility and the Wealthy

One could deduce from early skating texts that skating in the early days (1200-1600) was mainly practiced by the nobility. For them, skating was for play and leisure. It is likely that the manufacture of skates in the late Middle Ages was costly. Only well-to-do citizens could afford iron. Or perhaps, more was written about authoritative persons in that time than about the common man, creating a distorted perception of who skated.

The 1481 text about Mary of Burgundy from Bruges who skated among crowds suggests that skating was already popular at the end of the 15th century. It should be noted that Bruges was a prosperous city at that time with many wealthy traders and craftsmen. This could mean that skating grew mainly in urban centres.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, skating in the Netherlands was already practiced in all walks of life. A description by the Spanish captain, Alonso Vãzguez, from the last quarter of the 16th century indicates that women were not inferior skaters to men... ‘the women are very agile and do manual work without falling'. Skaters of a higher status often skated on separate ponds, which were usually privately owned.

Commoners

During the 18th century, skating in the Dutch provinces was increasingly seen as an activity for the lower classes. Women of higher rank, in particular, did not skate for moral reasons. This phenomenon did not occur in Friesland. In 18th-century public ice-skating rinks, nobles were found skating among shopkeepers and farm workers. An explanation may be found in the position Frisian country nobility occupied in Frisian society. In the 18th century, Dutch nobility adhered to French elitist fashion and the decorum of that century and would not approve of the somewhat rougher-looking skating style of the Frisians.

Women on Skates

Abroad, there was a perception that in the Netherlands, men and women participated equally in skating. In 1793 Gutsmuths cites the pedagogue Frank, who states: ‘The female gender finds strength enough in the Netherlands to brave the cold, while our hypersensitive girls are knitting behind the stove.’ During the second half of the 19th century women return to the ice, partly due to changing social relationships in which Dutch people were given more freedom to express themselves through their actions and thinking. In Amsterdam, the construction of the Vondelpark with its ponds provided an incentive for women from wealthy circles to move on the ice again.

The fashion-sensitive nature of skating can be deduced from inventories from the 17th and 18th centuries. The table below shows, in percentage terms over a number of periods, how often skates were found in the inventories of the Krimpenerwaard. Broken down by men and women:

1630 - 1670 1700 - 1729 1730 - 1764 1765 - 1795

Mannen 23 38 19 ---

Vrouwen 12 20 24 5

It is not entirely clear how sharp a distinction can be made between ice skates for men and ice skates for women. Adding up the percentages for the period 1700 to 1729 shows that skates are present in almost 60% of the families. Inventories are in themselves fashion sensitive. Inventories do not measure the value one attaches to an object. The table only shows that skating was popular in the first quarter of the 18th century. In the last quarter of that century, the popularity of skating dropped to a low point. This data is reasonably consistent with the belief that skating was primarily for commoners that began to occur in the second half of the 18th century. In the Krimpenerwaard, skating was more popular among farmers than the middle-class.

Differences in Status

The Frisian researcher Dr. O. Postma was surprised that so few ice skates were found in 16th and 17th century farm inventories. One explanation could be that skating in Friesland was one of the daily, albeit seasonal, items that were not valuable enough to be listed.

The differences in status applied more in Holland than in Friesland. It can be assumed that these differences also affected the type of skates that were used. Wealthy skaters wanted to distinguish themselves from commoners by purchasing expensive skates or by having them custom made. Expensive skates were often equipped with hard woods such as walnut, cherry or mahogany.

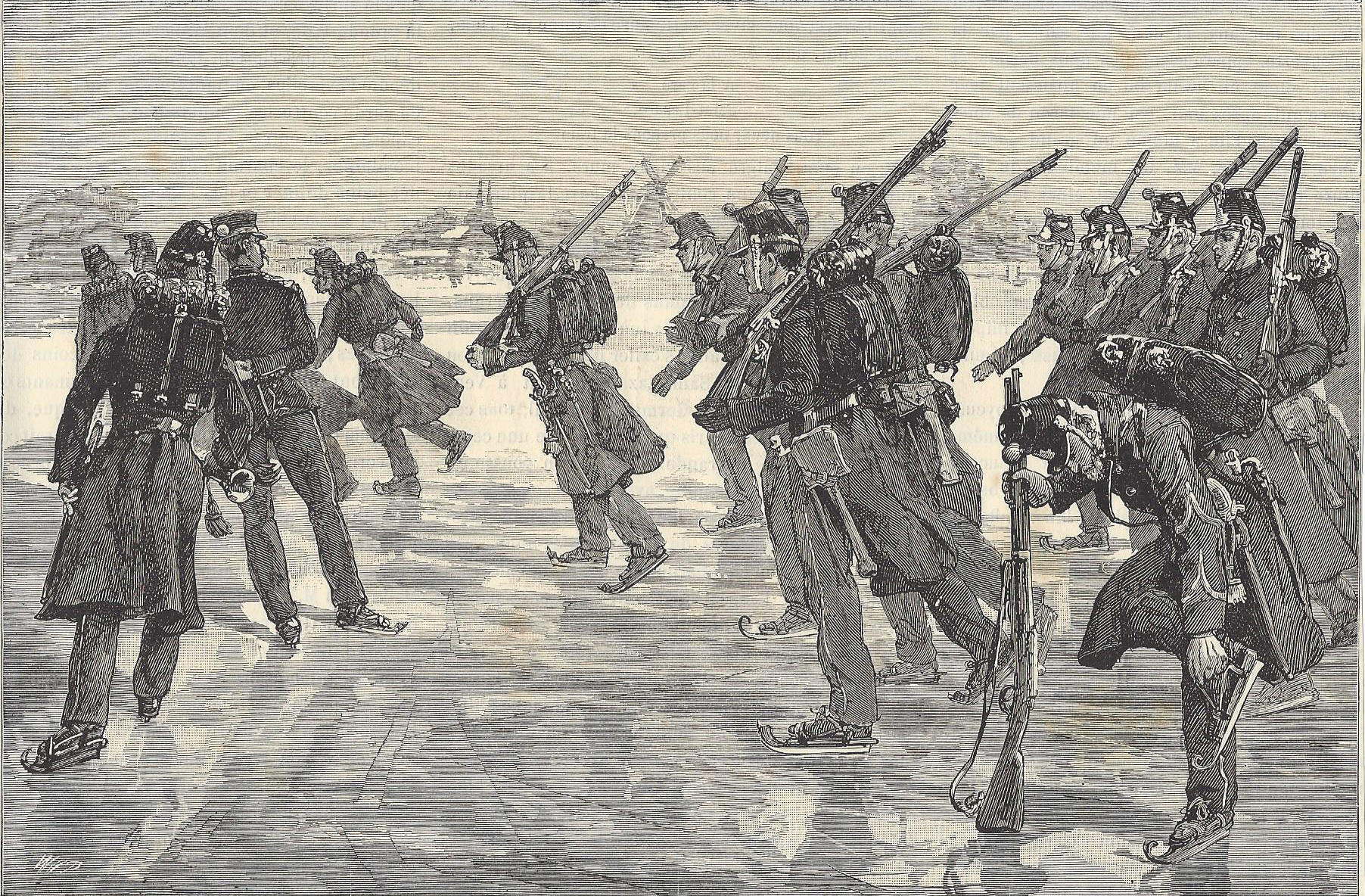

Soldiers

A special group of skaters were soldiers who carried out exercises on ice in winter so they could skate to the rescue should hostilities occur. And that was the case several times: among these, the siege of Haarlem (1572-73) and against the French in 1674. Exercises of soldiers on ice are known from the winter of 1609 on the frozen Wadden Sea and from 1848 on the city canals in Arnhem. These exercises were held until the winter of 1939-1940 when soldiers were mobilized for World War 2. Skating trips were also organized as an exercise for soldiers in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Sources

The article 'From Nobility to Commoners on Ice!' was written by Wiebe Blauw, De Poolster member.

It was previously published in his book, 'Van Glis tot Klapschaats' (2001)

Read more

More articles about the history of skating