Ice Skating History Abroad

Author Wiebe Blauw, 2001

Translation Cheryl Richardson, 2019

As mentioned in "The Origin of the Skate" it is almost certain that skating originated in the Low Countries meaning, the first skates were made and further developed here. Over time, ice skating became commonplace in other countries as well, often following the Netherlands’ lead. Gradually, different European countries developed their own traditions both in their style of skating and the construction of their skates. Eventually skating in other European and North American countries began to have a reciprocal influence on the development of Dutch skates and it is this influence that is discussed below.

Germany

Skating in Germany probably dates from the 15th century. The Swedish chronicler Olaus Magnus (1490-1550) wrote that ‘some bind a smooth iron or other slider under the sole’, from which it could be deduced that during that period, the slider and the wooden skate were used side by side. However, due to the less favorable climatic position of Germany for skating, it was not practiced on a large scale. Only during the 18th century did skating as a leisure activity become more common.

Skating was often practiced on ponds and lakes which influenced German skating style. Known eighteenth century skate models were indeed grafted onto Dutch long reach skates, but they were often shorter in design and sharpened on a curve to facilitate twists and turns in small areas. Poets such as Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724-1803) and Johann Wolfgang Goethe (1749-1832) wrote heroic and romantic poems about skating. The North German, Klopstock, preferred Frisian skates, while his friend, Goethe, from Central Germany preferred the Dutch curl skate. They contributed significantly to increasing the popularity of skating in Germany at the end of the 18th century.

Skating was often practiced on ponds and lakes which influenced German skating style. Known eighteenth century skate models were indeed grafted onto Dutch long reach skates, but they were often shorter in design and sharpened on a curve to facilitate twists and turns in small areas. Poets such as Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724-1803) and Johann Wolfgang Goethe (1749-1832) wrote heroic and romantic poems about skating. The North German, Klopstock, preferred Frisian skates, while his friend, Goethe, from Central Germany preferred the Dutch curl skate. They contributed significantly to increasing the popularity of skating in Germany at the end of the 18th century.

The pedagogue, Johann Christoph Gutsmuths (1759-1839), followed a more didactic description of skating in 1793 with his, ‘Gymnastik für die Jugend’, which also laid the foundation for gymnastics education in Germany.

A year later, the mathematics teacher, Gerhard Ulrich Anton Vieth, elaborated on the lessons of Gutsmuths in his, ‘Versuch einer Enzyklopädie der Leibesübungen’, in which he described not only the skate but a number of artistic figures as distance or touring skating was only possible in the swamp areas of East Frisia in north-west Germany and in the Spree basin to the south-east of Berlin. The skates used there were generally longer and sharpened.

During and after the Napoleonic wars there was little skating development in Germany. In 1860 a German translation of the book, ‘The Art of Skating’ by Cyclos (pseudonym for George Anderson, chairman of the Glasgow Skating Club) brought about a revival in German skating.

German skaters were found in three areas. In the steel town of Remscheid in the Ruhr area, many types of skates have been made since the beginning of the 18th century. Initially they were made according to traditional methods, but during the 19th century, machines began to produce skates in factories. This production focused mainly on exports to other European countries (including the Netherlands) and North America. In East Frisia and in the Spree area, skates were only made by village blacksmiths for the local market. A number of German skate manufacturers were inspired to choose factory signs with symbolic comparisons to "arrows" and "wings" that poets from the 18th century saw in skating.

For information about skate makers see: Skate Makers and Retailers in Germany (Schaatsenmakers en -verkopers Duitsland)

England

Gliding was described in England in the 12th century by Fitzstephen, Archbishop Thomas Becket's secretary. James Eccleston wrote in the introduction to ‘English Antiquities’ in 1847, that the sliders used by the people of London have "recently" been replaced by "real" ones. The German writer of sports history books Heinz Polednik assumes, and we believe with good reason, that this refers to Dutch skates. The use of wooden skates is only mentioned in English skating literature in the 17th century. Ice skating was probably introduced to England at the end of the 16th century in the Fen District (Lincolnshire) by French and Flemish refugees. Up until the 20th century, skates were still called "pattens" after the French word ‘patin’ meaning skate.

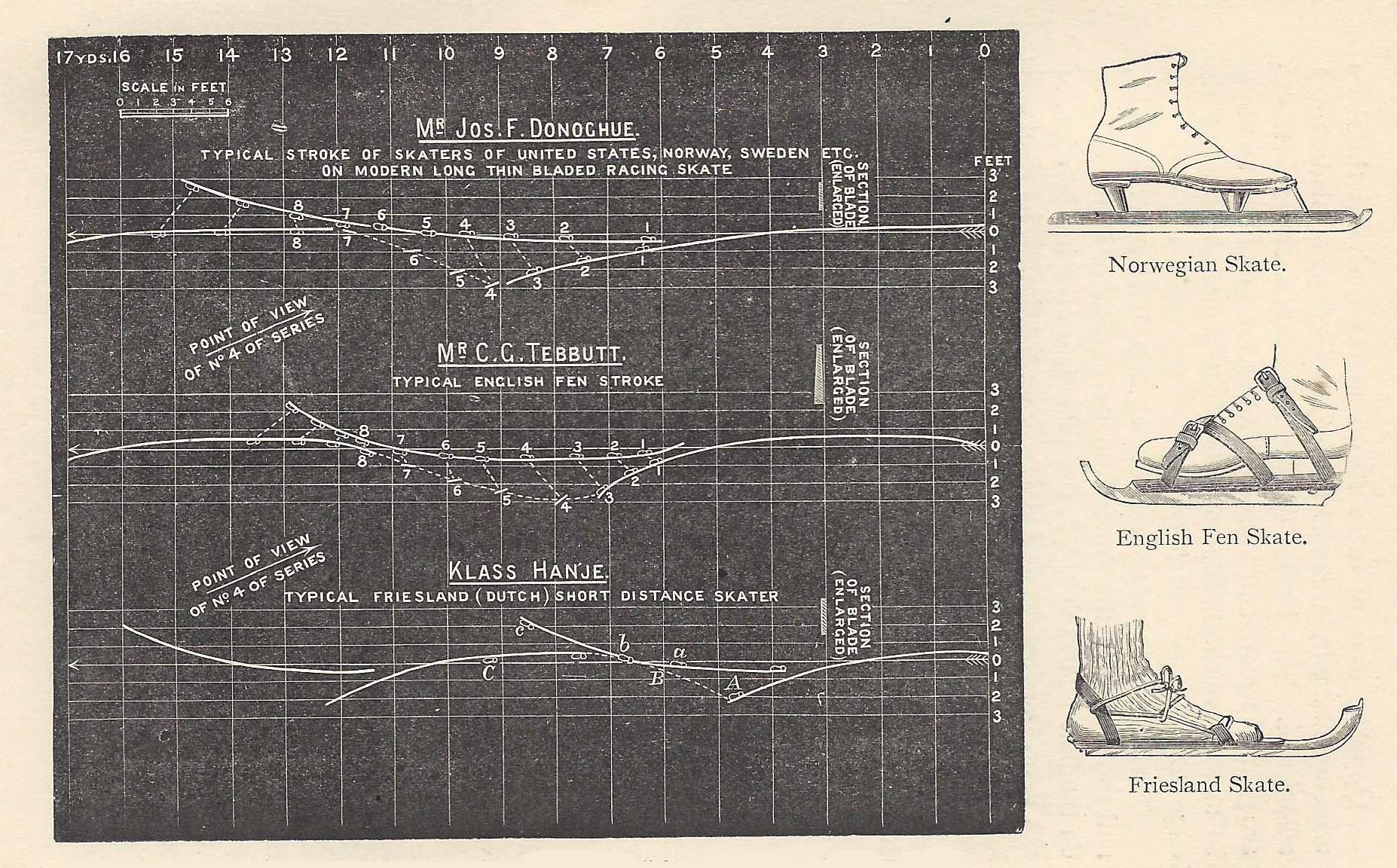

The Fen District used to be a vast swamp area that became ice rinks after the rainy season in the fall and winter. Around 1620, the Dutch engineer Cornelis Vermuyden was brought to the District to cultivate the marshy area by pumping it out. This produced muck soil with many, sometimes long, drains. Vermuyden recruited French and Flemish workmen for the implementation of his plans and also had Dutch workers come to England, who in winter, when the work stopped, enjoyed skating. The Dutch initially had little influence over the British style of skating but eventually Fen residents transformed their style into speed skating - perhaps in response to the newly arrived Dutch.

In the 17th century, the graceful Dutch curl was probably converted to a British skating model, the Whittlesea runner, named after the town of Whittlesea in the center of the Fen District. In the 18th century, long distance trips began in the Fen District. Suddenly, the area that had been virtually impassable during a mild winter became accessible to skaters moving over the frozen canals. Longer distances were also possible on the lakes of Cumberland (Lake District) in western England and on the lakes of Wales, but to a lesser extent.

In addition to the introduction of skating in England in the Fen District in the early 17th century, skating in London was also developing via a different route because of the relationship between the English royal family and the Oranges. The son of the English king James II, Monmouth, was taught canal skating in the Netherlands around 1660 under the guidance of his niece, Princess Mary. In return he taught Dutch ladies of high standing, the English Country dances. Because of Mary's marriage to William III, skating spread further in London. During the winter members of the English Court skated on London's park ponds, often in the presence of Dutch fishermen and traders whose ships were frozen in the London harbor. Since the size of the ponds was limited, skating was graceful. In the 18th and 19th centuries, England developed its own artistic skating style, which tended towards technical perfection.

In England, in the 18th century, skates were mainly made in Sheffield steel centers in factories dedicated to the production of all kinds of steel goods. In the Fen District, it was still mainly village blacksmiths who made skates.

For information about ice skate makers see, Skate Makers and Sellers: United Kingdom (Schaatsenmakers- en verkopers Verenigd Koninkrijk)

France

It is believed that the French have been skating since the 16th century. According to tradition, in 1548 King Henry II taught his mistress Diana van Poitiers to skate, very much against the will of his wife Maria de Medici. Trade and cultural exchanges with the Netherlands ensured that the French adopted skating from their northern neighbors. Paintings by Gillot, Watteau, Lancret and Boucher bear witness to a certain skating tradition in the 17th and 18th centuries.

In France, however, people had to rely on ponds and small lakes for skating. Skating was at that time reserved for nobles and courtiers, who belonged to the powerful elite of France. Skating spread very slowly among a wider audience.

The sport soon really developed with the support of Louis XVI. His wife Marie Antoinette was a woman with a deserving reputation for the arts. As a result, figure skating in France became an elite sport; skating in a straight line was the domain of the rural population. In 1791, Napoleon Bonaparte, then a student at the Ecole Militaire, narrowly escaped drowning when he skated on the canals of the Fort of Auxerre when he broke through the ice.

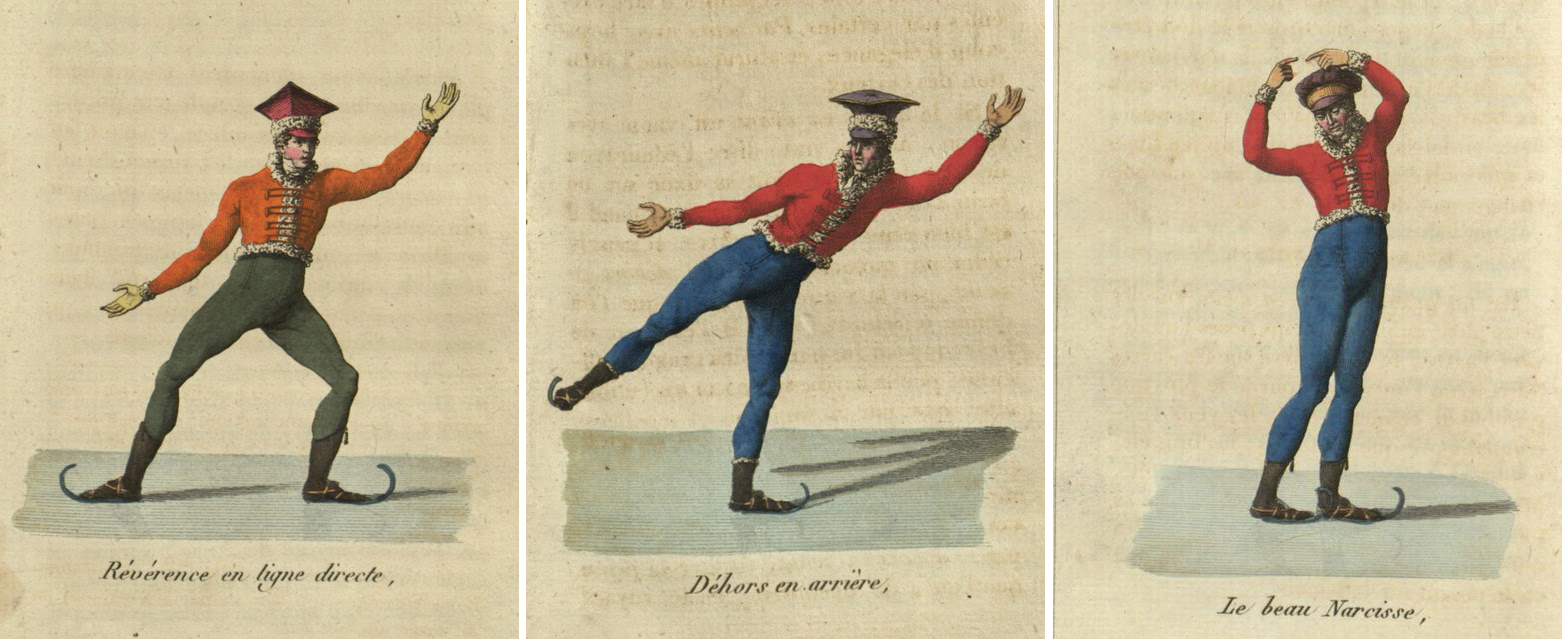

At the beginning of the 19th century the emphasis on the artistic performance of figure skating became stronger. A number of art lovers united in a formal club, the Gilets Rouges (named after their red jackets). French figure skating was interwoven at that time with adventurous artistic and acrobatic ice feats. In 1812 J. Garcin (himself a Gilet Rouge) wrote a book about figure skating under the title, Le Vrai Patineur. The book was not dedicated to an athlete, but to Mademoiselle Gosselen, Premiere Danseuse of the Imperial Music Academy. It was typical of the French approach to figure skating in which artistry predominated. Garcin added numerous new figures to the existing repertoire.

The skates used in France often displayed high curls to give extra joie-de-vivre to skating. Garcin also designed a special roller skate in Paris, probably so he could engage in his beloved sport outside the winter period.

No data is known about making skates in France.

Scandinavia and Russia

In many historical skating works Scandinavia and in particular Norway are considered the birthplace of skating. They invoke texts from the Edda, a collection of Old Norse gods and hero songs compiled in Iceland in the second half of the 12th century. However, these texts are infused with allegorical comparisons and symbolic references and connotations, and are not based on scientifically established data. The text does refer to ice-running, but this probably refers to a primitive cross-country ski.

In Scandinavian countries (Finland, Norway and Sweden) and Russia, there are many similarities with regard to the development of skating. Scandinavians and Russians have extensive lake areas. They also have to deal with long and often severe winters so conditions for developing a skating tradition are plentiful.

Yet skating in Scandinavia and Russia was in the shadows when compared to skating in the Netherlands. This was due to the abundant snow in the winter season. Clearing skating tracks in sparsely populated areas was impossible; all the more so because snow can fall on a daily basis. Scandinavians, and to a lesser extent the Russians, took advantage of snow by using skiing and cross-country skiing as a means of transport from the late Middle Ages. Even today, the number of skiers and cross-country skiers far exceeds the number of active skaters.

Artistic skating was practiced in Scandinavia and Russia in the 18th century but on a small scale since the areas of snow-free ice were small. This style of skating was given a boost under the influence of the American artistic skater, Jackson Haines who gave demonstrations of artistic skating between 1865 and 1870 in Oslo, Stockholm, St. Petersburg and many other European capitals. In Sweden the first book about skating in Swedish, appeared with the translated book of Cyclos. Under the influence of Haines skating tour figure skating became a popular sport in Sweden. Around 1880 speed skating in Norway was given an important impulse by Axel Paulsen who was highly skilled in both figure skating and speeding.

The Russians, who received Haines in St. Petersburg, greatly appreciated his performances. Perhaps his style reminded the Russians, culturally oriented to France, to those of the Gilets Rouges. Haines even became friends with Tsar Alexander II. Afterward his performances, ice parties were regularly held on the Neva in the presence of the imperial family.

From 1885, international competitions were regularly organized, with participation by Norwegians, Americans, British, Germans, Russians and Dutchmen. After the International Skating Union began to regulate skating in 1892, roller skating became an official competitive sport. Especially due to the successes of the Norwegians- Axel Paulsen and Carl Werner- the sport of ice skating became highly regarded in Scandinavia. Paulsen is considered the founder of skating in the north.

After 1880, speed skating also gained popularity in Russia. The Russian, Alex von Panschin, secured Russia’s place on the international scene.

Traditional wooden skates were originally used in Norway and Sweden in the 19th century. From 1885, when the popularity of both figure skating and speeding increased, factory-made skates became more popular. There was high demand for these skates abroad as well.

Middle Europe

In 1865 in Vienna, when Haines performed to music by Johann Strauss, he caused a furor with his interpretations of a waltz, a mazurka, a march and a quadrille on ice. His visit to Vienna led to the founding of the Viennese Skating Club in 1867. His own Viennese school emerged, which later formed the starting point for the International style of figure skating led by ISU. Not only did Haines add new figures to the repertoire (including the sit spin), he also designed a special skate that was used by artistic skaters for decades.

In Central Europe, only a few skate factories existed that mainly made figure skates.

North America

Skating was introduced in both Canada and the United States with the arrival of English troops. In Canada it began with the English takeover of French Nova Scotia in 1713. In the United States, British army officers arrived in Philadelphia around 1750. One of the first prominent American skaters in the second half of the 18th century was Benjamin West, who later became president of the Royal Academy. West was introduced to skating in London at the age of 24.

During the 19th century ice skating became increasingly popular. In 1848 E.V. Bushnell from Philadelphia designed the first complete metal skate, which would have a major influence on the sport of figure skating. In 1865, another revolutionary designer was the Canadian, Forbes from Halifax (Nova Scotia). His skate could clamp the shoe to the skate by means of a lever system. In the 19th century, many new figure skates were designed to improve the performance of skaters. Patent applications were made for every small, new adjustment.

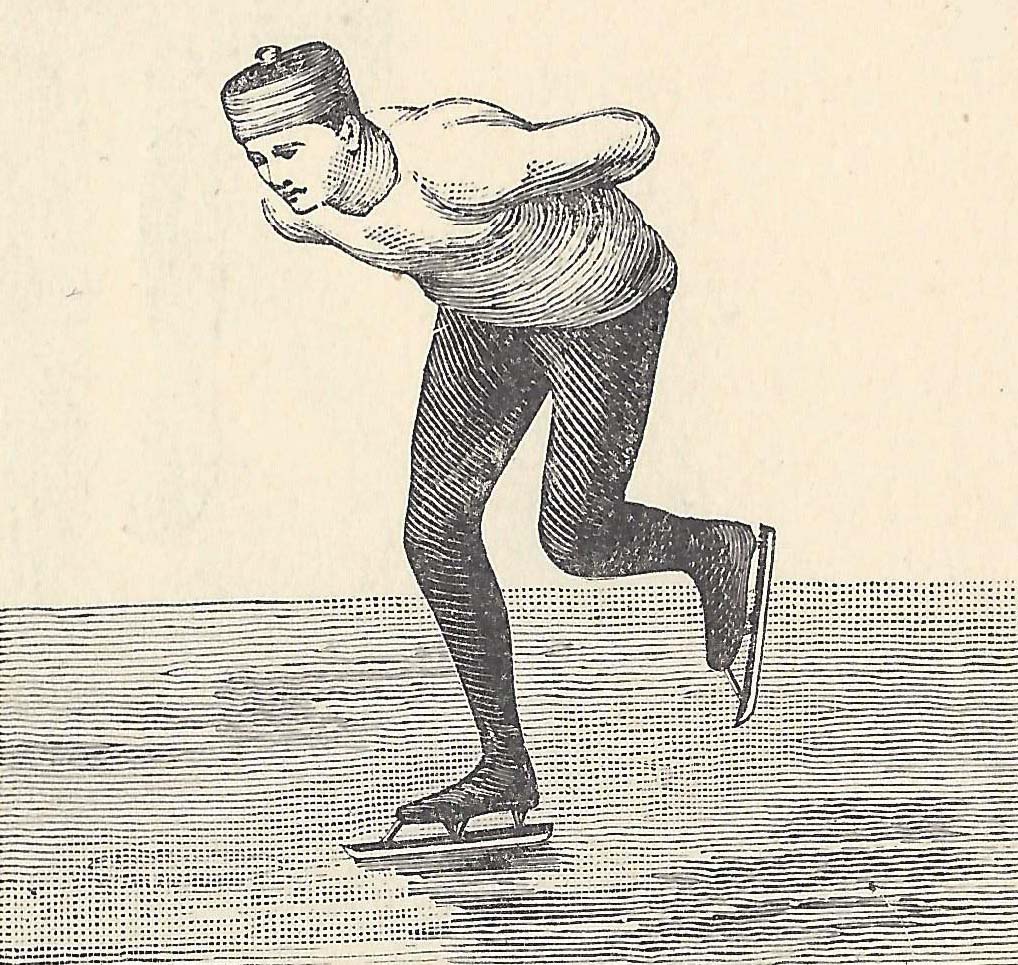

In addition to figure skating, North Americans also traveled long distances. In 1878, John Ennis, of Chicago traveled 100 miles in 11 hours and 37 minutes and 145 miles in less than 19 hours. In 1879 the first championship over 10 and 20 miles was held in America with the winner G.D. Phillips. Speed skating started in the last quarter of the 19th century. In 1891 the American Joseph F. Donoghue became the first unofficial, long-distance world champion while competing with amateurs in Amsterdam.

From 1850, skate manufacturing in North America increased. Initially, figure skates were the main type of skate made but after the successes of American speed skaters post 1880, speed skates were also made.

Sources

The article 'Skating History Abroad' was written by Wiebe Blauw, beneficiary (member) of De Poolster. It was previously published in his book 'Van Glis tot Klapschaats' (2001).

Some corrections by Bev Thurber (2023)

Read more

More articles about the history of skating