Skating at the court in The Hague | 1392-1418

Author Niko Mulder, 2017

Translation Cheryl Richardson, 2021

Schoverlings and skates from Amsterdam

|

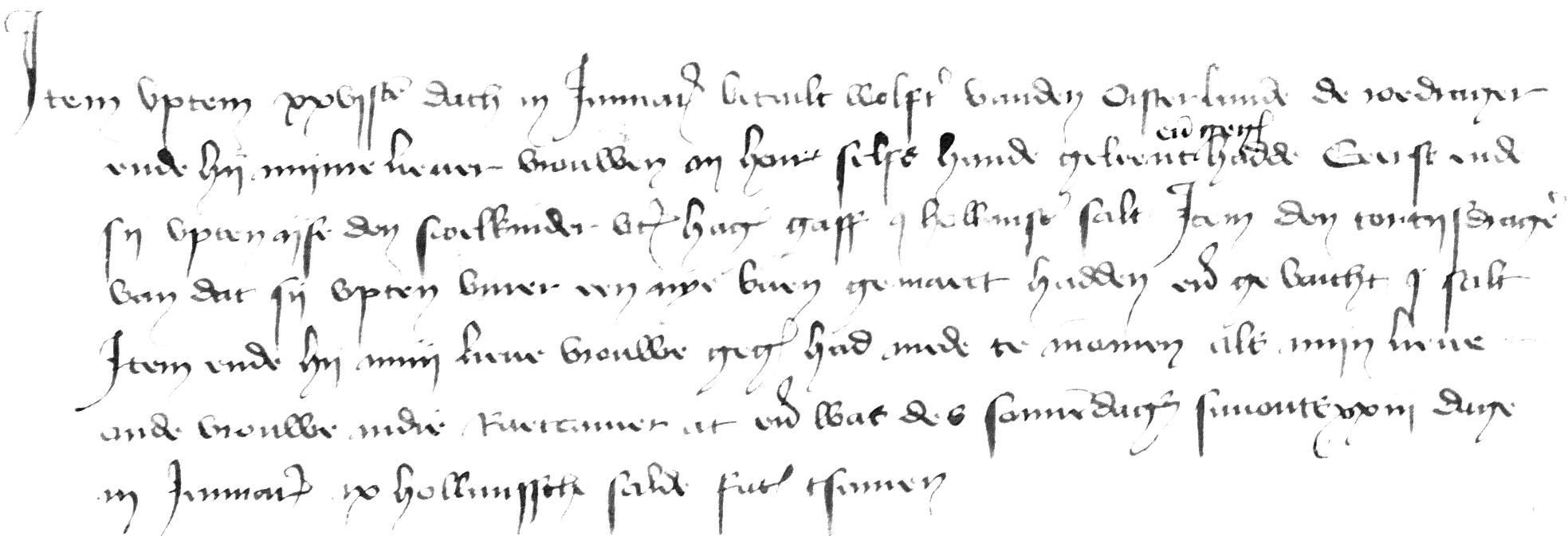

Item mijn heer Van Oestervant screef den scult enen briif dat hi hem zende zoude III paer scouerding ende III paer scaetzen, die Dirc leuerde her Peter vanden Zande, costen XL s. |

Willem van Oostervant, eldest son and heir to the throne of Count Albrecht van Beieren, requests the sheriff by letterthat he send him three pairs of blades and tree pairs of foot-stock.Sheriff Dirk supplied them to Mr. Pieter vanden Zande, secretary and chaplain of Willem van Oostervantfor 40 shillings. |

At the court in The Hague, expenses were accounted for in great detail. Although the posts seem insignificant, they provide us with fascinating insights into court life, such as the previously mentioned order of three pairs of foot-stock and three pairs of blades from Amsterdam, most likely placed between December 1, 1392 and the end of February 1393. That winter was recorded as normal. Little is known about it, but apparently it was possible to skate for some time although it is questionable whether the foot-stocks and blades were delivered on time.

Medieval nonetheless!

Deriviations of the words 'skate' and 'schoverling' appear here in literature for the first time. Although these words do not appear in the Middle Dutch dictionary in this sense, it appears that they were already in use at the end of the 14th century.

Scouerding (pronounced: scoverding) was later corrupted into 'schoverling' in the Northern Netherlands and it was probably the origin of the Flemish 'scaverdine' that eventually became 'schaverdijn'. According to Verdam, both words may have been derived from 'planing' or 'shoving' (quickly moving away), just like the Groningen 'scheuvel' and the 'schöfel' from Eastern Friesland in Germany.

Foot-stock and iron blades separately?

Willem van Oostervant’s order was probably not for two different models, but for three pairs of wooden foot-stock (scaetzen) and matching blades (scouerding). In the Middle Ages the word 'skate' always stood for a wooden support, such as stool, stilt (in Flanders) or trestle. Unfortunately, the original letter was lost, but from the fact that blades and wooden foot-stocks are mentioned separately from each other, we may conclude that the blacksmith and the maker of the foot-stocks delivered their semi-finished products independently of each other. Afterwards, the skate maker or woodworker would supply the finished product; at least that was how things were organized in Amsterdam around 1500. Because of this, the word 'skate' eventually came to refer to the whole thing, i.e. the combination of blade and foot-stock.

If the wood and blades were delivered unassembled at the end of the 14th century, we can assume this also meant that both parts could be put together quite easily. Presumably they pushed the nose of the foot-stock under the tang (a horizontally knocked back iron pin at the neck of the blade), pushed the blade into the groove at the bottom of the foot-stock causing the blade to be wedged between the tang and the vertically folded iron hook at the back; (horse shoe) nail or common nail through it and ready-to-use! This type of connection would remain in use for centuries.

Or two separate models?

In theory, scaetzen could also be wooden planks without blades on which ladies in particular liked to be pushed. As a result, scouerding would be understood to be skates with a single 'toe pick'. Ice skates with such a toe pick were ideal for pushing the ladies on their planks because of their grip on the ice.

The problem with this assumption is that this practice of pushing - so far - was only known in the Southern Netherlands, and moreover, only in the late 15th and 16th centuries. This explanation, therefore, seems less likely for Holland in 1393.

Amsterdam has it ...?

Why weren't the skates just ordered from a blacksmith in The Hague? Was it a coincidence that Sheriff Dirk Simonsz, a wealthy Amsterdammer who regularly advanced payments for the Count and sometimes stayed at the court in The Hague for days at a time, was given this assignment? Or did the makers of foot-stocks and skate blades from Amsterdam before 1400 have such a reputation in their field that Willem van Oostervant had to have them from there? A century later, Amsterdam skate makers were the only ones in the world who formed a separate professional association and were part of a woodworkers' guild according to the bylaws of 1497 and 1551. It is not known whether their specific expertise was in use at the end of the 14th century, but this order could indicate that.

Department of Archaeology Municipality of Amersfoort.

With thanks to Timo d'Hollosy.

The commission could also be explained by the discovery of a new model that may not yet have been manufactured in The Hague yet, for example a skate with a long nose without a toe pick. After all, with the sideways pushing method now mastered, the pick on the neck of the skate became superfluous. In addition, you could put your long pike-toed shoes on the protruding wooden nose of the skate. However, there is no certainty about such an early development of a skate with a long low neck.

Price tag

Forty shillings for three pairs of skates at that time roughly corresponded to the price of a simple sword. Even the luxury of one pair of skates was far from something everyone could afford.

Too little allure?

Photo: © Department of Archaeology Municipality of The Hague

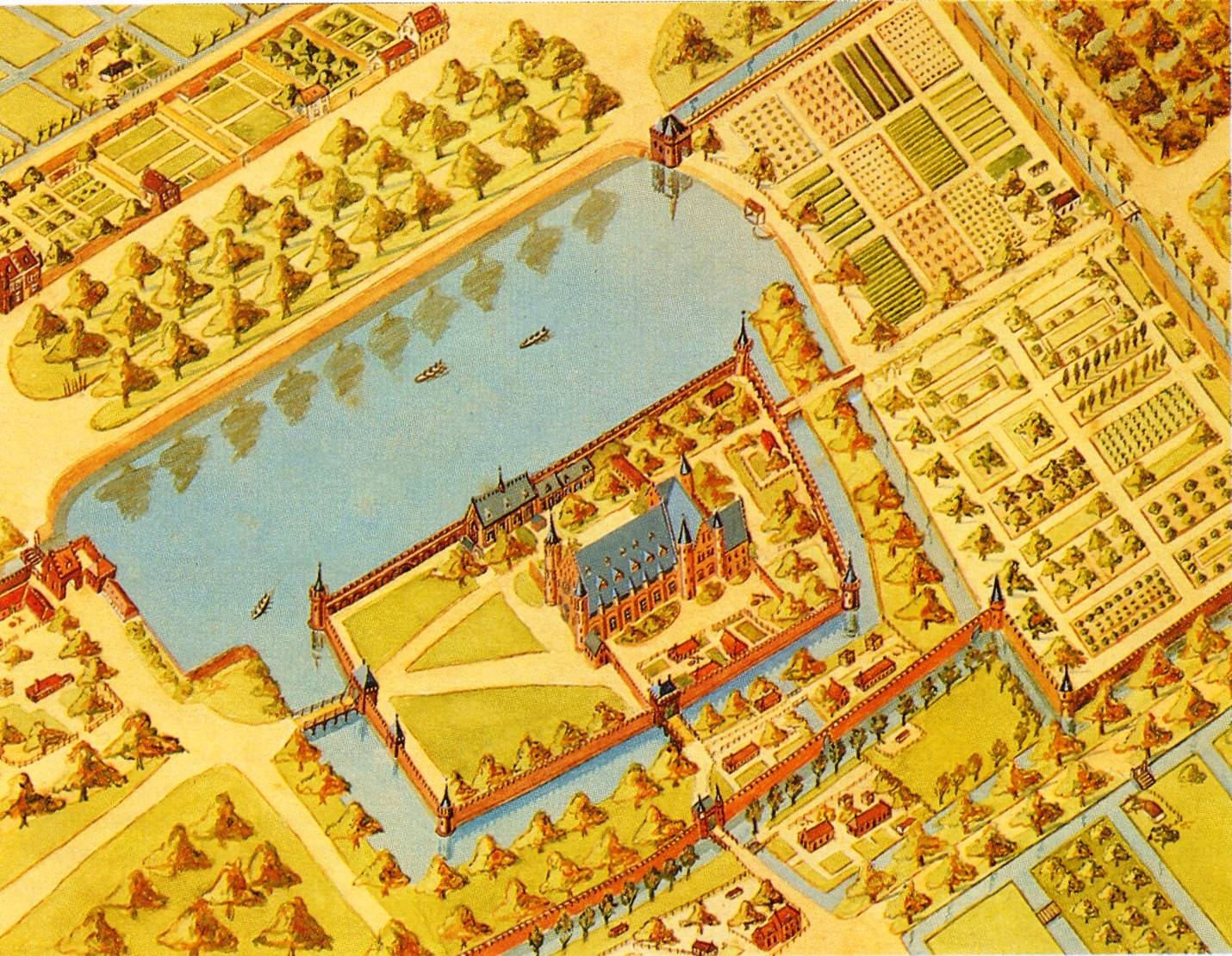

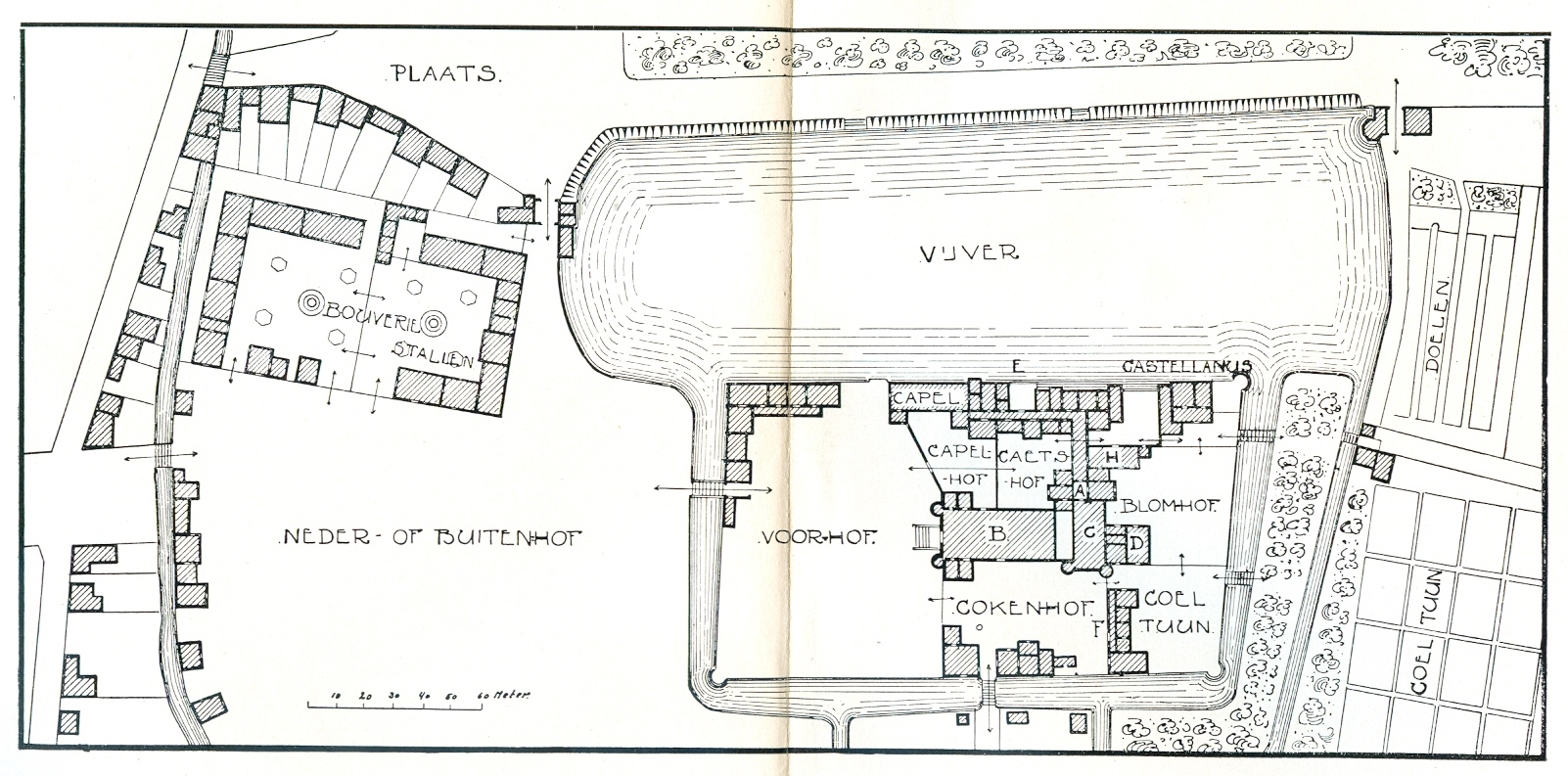

We do not know whether the skate with a single toe pick found in the Oude Hofgracht in The Hague was part of Willem van Oostervant's 1392 order. The triangular strap holes in the poplar wood are unsuitable for the wide leather straps you would expect in a pair of court skates. The shape of the strap holes may indicate that it wasn’t just the nobility who skated. At the end of the 14th century citizens were already using ice skates in the neighbouring town of Schiedam. In the case of the Hague skate, however, it is obvious to think it would be someone from the large court and not an outsider, because sources show that not everyone had free access to the walled complex. In 1363 people were paid 'to bite the viver in the Haghe', meaning to bite (chop open) the ice of the court pond to prevent attacks and robberies. Two years later the tower was guarded for an extra 14 days 'doet ys lach' (when there was ice).

For whom were the skates intended?

Willem van Oostervant placed the order. He stayed in Holland from November 1392 until the end of February 1393 to visit the court of his father, Albrecht, in The Hague. It is not inconceivable that Willem's young wife - Margaret of Burgundy who was only 18 - travelled with him from Le Quesnoy in Hainaut. The couple had a spacious residence right next to the cabbage garden in the courtyard, which bordered the inner moat on the south side.

The skates ordered, or some other pairs of them, could of course also be used by the staff of Willem and Margaretha. Chaplain-Secretary Pieter vanden Zande was one of them.

Count Albrecht was 56 and presumably still quite vital, although it is questionable whether he was interested in this entertainment. Two people from his entourage who were close to him, his beloved Aleid van Poelgeest and his masterboy Willem Cuser, were murdered at court on September 22. The fuss about it seemed to have subsided during the winter, but would flare up again and have a long aftermath as part of the Hook and Cod Wars.

Changing opportunities in barbaric times

The Hook and Cod disputes were mainly about the influence of nobles on the power at court, where the odds could turn quickly.

The murder of William Cuser in the spring led to a trial and a verdict in the form of a major cleansing. A large number of Hook nobles had to leave court, and their castles besieged and demolished. When William of Oostervant stood up for them, it led to a split between him and his father Albrecht that lasted for over a year. The split ran right through the Count's family. The conflict also affected the other persons involved in the delivery of the batch of skates. Pieter vande Zande was dismissed from the court of Willem van Oostervant by order of Count Albrecht.

Sheriff Dirk Simonsz Abbe (who also called himself Benning or Benninck) initially remained a supporter of the Count. After the death of Count Albrecht in 1405, Simonsz, a prominent Cod, was involved in an uprising against William of Oostervant, now called William VI. The new Count had the former sheriff arrested and beheaded without mercy. He would not have remembered the delivery of the lot of ice skates from that time.

With rented sleds and colf clubs over the ice to Delft

Ice skating wasn’t the only winter entertainment at court. This was evident in the severe winter of 1395-1396, which started early. A post from the December 1395 accounts reads:

|

… als mijn here ende mijn vrouwe op te ijse Delfwairt gaen wouden, betailt van colven, ballen, van sleden te huur, die mijn vrouwe weder invoirde … |

When Count Albrecht and his (second) wife Margaret wanted to cross the ice towards Delft,they paid for the rental of colf clubs, balls and sleds,that Margaret had returned.. |

.jpg?1484407352487)

Found in: The four seasons in the art of the Low Countries 1500-1750, p. 39.

We will never know if Count Albrecht and Margareta van Kleef, his young second wife, also skated on the Monday after Saint Nicholas. The couple probably owned skates themselves, so they wouldn't have to rent them and that's why skates were not mentioned in the accounts. It is noteworthy that colf clubs and sleds were not part of the court's inventory. It is also notable that Margaret van Kleef and not Albrecht had rented and returned the items. Had she taken the initiative for this winter entertainment?

The martyrdom of Crispinus and Crispinian, detail

Aert van den Bossche, 1494.

National Museum, Warsaw. Wikipedia.

Track sweepers on the ice!

|

Item. (swoensdages na sinte Katharinen dach) bi mire vrouwen bevelen den knechten, die hair upten yse een bane scoen maecten, gegeven xviij gr. |

On the Wednesday after the feast of St. Catherine (November 25th) Margaret gave the order to the servantsto sweep a track for her on the ice:paid 18 groats. |

Very early in this otherwise mild winter, on November 28th 1397, Margaretha van Kleef had the servants do an ice sweeping job. It’s the first mention of ice sweeping in history. The post does not mention whether there was sweeping on the canals or on the court pond, which at the time was still enclosed on the outside by walls.

The oldest ice rink in the world

Over twenty years later, in the third week of January 1418, Countess Jacoba of Bavaria, the only child of Margaret of Burgundy and William VI, took a day off to enjoy the ice. Her father had died the year before from a dog bite and Jacoba, although only 17 years old, had already been a widow for nine months.

|

Item uptem xxvisten dach in Januario betailt wolfert vanden Oisterlande de roedrager ende hij mijnre liever vrouwen an hoir selfs hande geleent ende gegeven hadde. Eeerst ende sij upten ijse den scoelkinder uten hagen gaff 1 hollansen scilt. Item den tortijsdragere van dat sij upten viver een nye baen gemaect hadden ende gevaicht 1 scilt Item ende hij mijn lieve vrouwe gegeven had mede te mommen als mijn lieve oude vrouwe indie Raetcamer at ende wat des sonnendages savonts xxiii dage in Januario ix hollanssche scilde facit tsamen xxxvii s. vii d. groot |

Item paid on the 26th day in January to Wolfert van den Oosterlande, the bailiff,what he had lent and given to my dear lady (Jacoba) in her own hands.Firstly, what she gave to the schoolchildren from The Hague on the ice: 1 Dutch shield.:Item to the torchbearers because they made a new track on the pond and swept: 1 shield.Item he had given my dear lady to disguise withwhen my dear old wife (Jacoba's mother, Margaret of Burgundy) ate in the Council Chamber, and some other expenses on Sunday eveningon the 23rd day in January: 9 Dutch shields.That makes a total of 37 shillings and 7 pennies. |

The settlement of the amounts advanced to Jacoba by the court clerk Wolfert van den Oosterlande shows that during this cold January 1418 various activities took place on and around the ice of the court pond. Jacoba gave a gift to the schoolchildren from The Hague - undoubtedly from the better families. Whether there was skating or whether the children even had skates at all at that time the accounts, of course, do not mention.

Apparently there was skating that winter before the pond was snowed over, because she had the torchbearers sweep a new rink. So the Hofvijver in The Hague has been in use as an ice rink for about 600 years and is undoubtedly the oldest in the world. People still skate there when King Winter allows it.

Furthermore, Jacoba spent a large amount of money on partying. Was the time-honored lover's party Angen (St. Agnes on January 21), in which girls usually went along the houses of single boys, dressed and masked, celebrated on occasion on the frozen court pond?

Trick skate

Many (skating) historians have already been misled with a particularly intriguing mention in the accounts of the countship from 1398. Thanks to Antheun Janse we know better:

|

XII piecstaffen voir mijn here mede te vlieghen mit ijsers aen de voeten |

12 poles with iron tips at the ends for Count Albrecht to catch birds with |

Bodleian Library Oxford, Douce 6, folio 004v, detail. - circa 1325

These 'irons on the feet' do not refer to skates, but to iron tips on the ends ('feet') of poles ('piecstaffen'), which were used in bird hunting (the so-called 'flying') to attach the nets on with which birds were caught.

So there is no connection whatsoever with ice amusement. Poles by that time had not been used for over a century in skating; an incorrect interpretation of the fragment would have given a completely wrong picture of the development of skating.

Comments on this article can be sent to redactie@schaatshistorie.nl of n.mulder@hccnet.nl.

Niko Mulder

14 januari 2017

Translated by Cheryl Richardson

January 2021

Sources

- B. ARA Den Haag, archief Graven van Holland, inv. Kort no. 2027 = 4e rekening van Dirk Simonsz, schout van Amsterdam, 1392 dec. 1 – 1393 dec. 1, p. *8, uitgaven.

- B.R. de Melker – Oorkondenboek van Amsterdam tot 1400 - supplement (1995), p. 54-55

- Jan Buisman - Duizend jaar weer, wind en water in de lage landen, deel 2, p. 314; 331; 336; 429

- J. Verdam - Over het woord ‘schaats’. Bijdragen en mededeelingen Akademie van Wetenschappen 1907, p. 371-372; p. 374-375

- A. Carmiggelt – Tussen Hof en Herberg – Archeologisch onderzoek aan de zuidzijde van het binnenhof in Den Haag (VOM-reeks 1992, nr 1), afbeelding 25E; p. 15

- Mededelingen Monique van Veen, afd. Archeologie, Dienst Stadsbeheer, Gemeente Den Haag) 24 januari 2006

- Niko Mulder - Ten IJse (4) – Met scaetzen en scouerding op de hofgracht, in: Kouwe Drukte 36, oktober 2009

- Jhr G.G. Calkoen – Het binnenhof van 1247-1747, p. 46; p. 142 noot 11in: Die Haghe, bijdragen en mededeelingen, 1902 (ijsbijten)

- C.H. Peters – Het Grafelijk leven in die Haghe, in de tweede helft der XIVe eeuw, in: Die Haghe, bijdragen en mededeelingen, 1909.

- Wiebe Blauw – Van glis tot klapschaats, 2001, p. 96-97

- Niko Mulder - Het schaatsenmakersgilde – een unicum; in: Acht eeuwen schaatsen in en om Amsterdam – Niko Mulder / Jos Pronk, 2014 (gewijzigde herdruk), p. 13-14

- M.J. Waale – De Arkelse oorlog, 1401-1412 (1990), p. 243 (Pieter vanden Zande); p. 70 e.v. (conflict tussen Albrecht en Willem)

- H.E. van Foreest - Traditie en werkelijkheid. C. Au lieu et heure que la femme y moru, uit: Bijdragen voor de Geschiedenis der Nederlanden 22 (1968-69) 171-208 (toedracht moord op het binnenhof).

- Eenheid en verdeeldheid. Politieke en sociale geschiedenis tot in de zestiende eeuw – M. Carasso-Kok / C. Verkerk, in: Geschiedenis van Amsterdam tot 1578 (2004), p. 224 (moord op Dirk Simonsz Abbe)

- F. van Oostrom - Het woord van eer. Literatuur aan het Hollandse hof omstreeks 1400, p. 28 (1987)

- Eelco Verwijs - De oorlogen van Hertog Albrecht van Beieren met de Friezen in de laatste jaren der XIVe eeuw citeert een rekening uit Cleen Foreyn, fol. 80r voor 28 november 1397.

- Antheun Janse – Een pion voor een dame. Jacoba van Beieren (1401-1436), 2009, p. 138

- Tresorier- en kostenrekening 1417-1418 van Jacoba van Beieren, folio 56 verso, archiefstuk uit de collectie De Merode-Westerloo 1786. Met dank aan Gerben Schooneveldt namens de Societas Palaeographica voor de transcriptie en hertaling van het fragment.

- Anoniem - Huizen van Holland, Henegouwen en Beijeren, in: Mededeelingen van de Vereeniging ter Beoefening der Geschiedenis van ’s-Gravenhage, p. 319 (huursleden);

- p. 319: Coman Floris in den Haghe betaelt hr Jan Heerman van XII piecstaffen voir minen hée mede te vlieghen mit ijsers an de voeten, die aan te doen zetten, mit dat hire om virteerde, als hire om getoge was tot Rott’dam, als hi aenbrocht IIII oud.sc.

- Antheun Janse - Ridderschap in Holland (2001), p. 346 (vogeljacht)

Read more

More articles about the history of skating