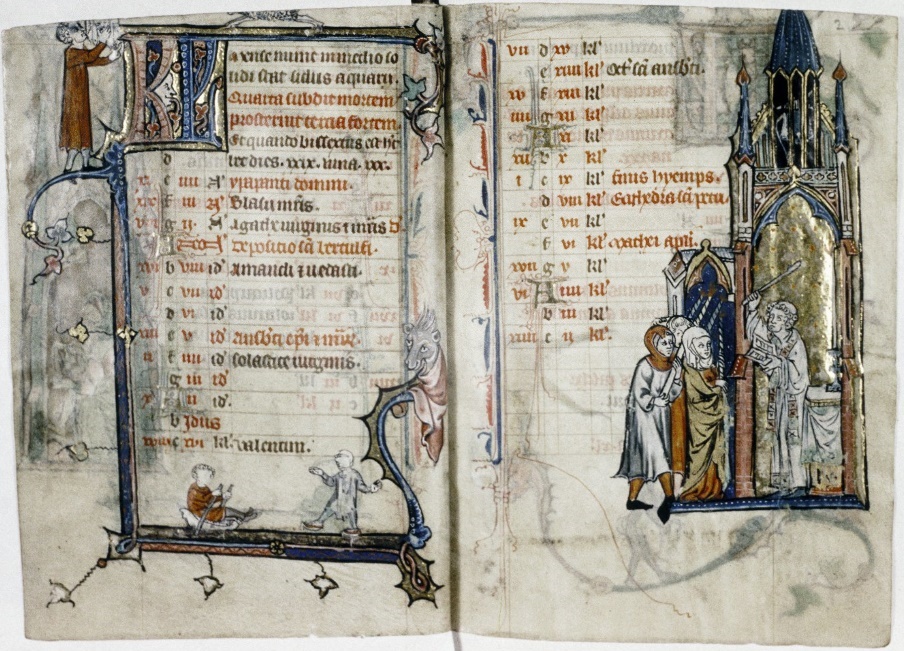

Circa 1325 – Sledge and skater on a miniature from a Ghent prayer book

Author Niko Mulder

February calendar sheet from a two-piece prayer book

Anonymous miniaturist

Circa 1325, Ghent, possibly in association with the Saint-Veerle Church, the Court Church of the counts of Flanders

Oxford, Bodleian Library, ms Douce 5, fol. 001v

9,5 x 6,5 cm

Bodleian Library Oxford, Douce 5, fol. 001v - detail

150 years ahead of his time

The calendar page for the month of February of a Ghent prayer book from circa 1325 depicts two winter games: sledding with prickers on a horse jaw and ice skating. They are by far the earliest images we know for both forms of entertainment.

Bodleian Library Oxford, Douce 5 fol. 007r – detail

Bodleian Library Oxford, Douce 5 fol 008r – detail

With this scene the artist broke with a long tradition, because for centuries calendar images at the months as we know from medieval manuscripts were pretty stereotyped. They show the work of the farming population throughout the year, sometimes supplemented by noble entertainment such as excessive dining, jousting, hunting or courting between knights and damsels in May. Thus the fixed roles in society were confirmed: the lower classes had to work and the nobility (and gradually also rich townsmen) should have fun.

Bodleian Library Oxford - Douce 5 fol. 001r – detail

Bodleian Library Oxford - Douce 5 fol. 003r – detail

For the winter season the psalterium from Ghent almost entirely meets the 'rules': a cow is slaughtered in November, we see a baker at work in December and in January a man warms up by the fireside, while – less common - a boy roasts a bird on a spit. Usually at the end of winter trees are pruned or fields plowed, but here the anonymous master turned out to be more than 150 years ahead of his time: pruning could wait until March, as the nobility was allowed to have some winter fun first.

This winter scene fits in well with the winters of the 1320s. They ranged from normal through cold to severe; the winter of 1322-1323 was nothing less than harsh.

Pricker sledge

The image of the jaw sledge in the Ghent psalter is in line with archaeological excavations from about 1300 in Hulst in Zealand Flanders and from Vlaardingen, circa 1325. This latest jaw sled is found in an old moat and comes – just as the image from Ghent – very close to the entertainment of nobility. However, it is almost inconceivable that the elite at that time would have been satisfied with a horse jaw to race over the ice with. That it is child’s play we see here, makes the scene a lot more plausible. Maybe that should be concerned the most important insight the artist provides us.

Bodleian Library Oxford - Douce 5 fol. 001v – detail

Pricker skate

Bodleian Library Oxford - fol. 001v – detail

The foremost skate of the boy who somewhat clumsily tries to keep his balance, has a large (double?) hook on the front. It is meant to represent the prick point of the pricker skate. At the rear skate such a spike is not visible, perhaps because it is hidden in the ice at the moment of pushing off. It is also possible that only one skate had a spike.

The spike on the front skate is depicted larger than it was: it goes much too far down. In reality the prick point obviously was shorter, so that it did not get in the way during the gliding phase.

Also the curve of the skate is exaggerated. Were blades really grinded that way to be able to turn easily or skate elegantly? With the oversized spike and outrageous curvature in the blade it seems that the miniaturist - a very skillful artist –tried to highlight the essence of the way people skated in his time, even though we can barely imagine the combination of a forward push and a graceful glide.

Gift of the count of Flanders

Even though the scene with skating and sledding indicates noble entertainment, for the high-born children at least, not every nobleman (or wealthy citizen) could afford such a richly illustrated two-volume manuscript. Because of the coat of arms with a black lion rampant on a yellow field, that is shown on shields, banners and cloaks in the manuscript, the French historian Jean Wirth considers the man who commissioned the books to be the count of Flanders, in this case from 1322 to 1346 Louis of Nevers.

Bodleian Library Oxford - Douce 6 fol. 044r

Because of that ducal commission Wirth does not think the Ghent psalters originated in St. Peter's Abbey on mount Blandin, as researchers previously assumed, but he lays a connection with the canons of the church of Saint Veerle, the court church of the counts of Flanders.

Whether the prayer book was meant as a gift for Louis’ wife Margaret, daughter of the French King Philippe V, or for a mistress, Wirth is not sure of. He seems to lean towards a mistress because the fleur-de-lis, the French lily on the coat of arms of the French monarchs, is not depicted at all in the two-volume manuscript.

It is not clear whether the image with winter fun is added at the request of the young count. I do not think that a childhood memory of Louis is portrayed. He grew up in Nevers on river Loire in the heart of France and afterwards at the royal court in Paris. Whether people already skated in France in the beginning of the 14th century is not known, but must be seriously doubted.

Original inspiration?

To me the scene on the ice rather seems an original inspiration of the Ghent miniaturist, who, as far as we can ascertain from many of his bold pictures, enjoyed much freedom of action. Whether an ice scene was pictured in a previous work, psalter 3384 that is now located in the Royal Library of Copenhagen, cannot be determined anymore, because the calendar of that handwriting unfortunately is lost.

Bodleian Library Oxford, Douce 5 fol. 001v - 002r

Source

This article is written by Niko Mulder, supporter (member) of Stichting De Poolster. The content of the above article may not be used for other publications without written permission from Niko Mulder (red.)

- Het jaar rond – Kalenderbeelden in Vlaamse handschriften – Katharina Smeyers in: De vier jaargetijden in de kunst van de Nederlanden, 2002, p. 37-49

- Duizend jaar weer, wind en water in de Lage Landen, deel 2 – Jan Buisman, 1996

- Website archeologiehulst

- VLAK-verslag 4.2 - ‘D’ Engelsche boomgaert 6.123 - Het botmateriaal, Paalman, Esser, Robbers, De Ridder, 2002

- Website geschiedenisvanvlaardingen

- Les marges à drôleries des manuscrits gothiques, 1250-1350 – Jean Wirth, 2008

- Collaboration in a Fourteenth-Century Psalter: The Franciscan Iconographer and the two Flemish Illuminators of MS 3384, 8o in the Copenhagen Royal Library – Kerstin Carlvant in: Sacris erudiri, volume 25, 1982, p. 138

- Bodleian Library Oxford - Douce 5

- Wikipedia Prikslee

Read more

More articles about the history of skating