The oldest skate text and images come from Flanders, ca. 1333

Author Wiebe Blauw, 2001

Translation Cheryl Richardson, 2018

Written texts and images about the origin of skating are scarce. The oldest come from Flanders. In 1511 a 1333 text was quoted that mentioned reports of jousting on skates in Leuven; two silver skates were the main prize.

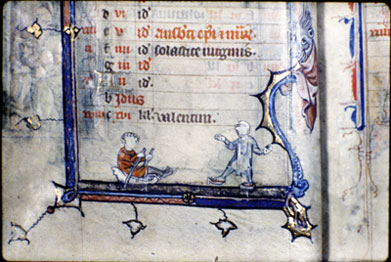

It is a miniature in a Gothic manuscript from Ghent.

The oldest image of a skater is also from Flanders. It is a miniature illustration of a sleigh and a skater appearing in the Saint Pierre van Blandigny calendar at Gentin. (ca 1330). The skate depicted shows similarities with skates from the 13th century that were found in Amsterdam and Dordrecht. In an illustrated rhyming chronicle from the 14th century, people can be seen happily mingling and skating. In 1398, Count Albrecht of Holland, who had his seat in The Hague, mentioned ‘te vlieghen mit ijsers aan de voeten’ ('to fly with iron runners on the feet').

From the 15th century on, the number of skate references increased. There are known texts about skating in the winters of 1464-1465 and 1465-1466. In January 1465, skating was even given historical significance in the conflict between Duke Arnold van Gelre and his son Adolf. Duke Arnold wanted to remain ruler while his son wished his father to submit to the Flemish-Burgundian monarch. During a visit to his father in Grave, Adolf tried to persuade him but left without success. Duke Arnold suspected that he had successfully repelled his son's attack. But one evening after the castle bridge was drawn, Adolf and a few friends skated over the moat around the castle and managed to overpower his father which ended his reign.

In the winter of 1465-1466, the Bohemian Baron Leo Rozmitalis traveled through western and southern Europe to seek support for attacks from the east after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. In Brussels he stayed at the court of Duke Philips for three weeks. Winter was very cold that year and during his stay he was very surprised to learn about skating and he himself learned how to skate. In 1481 Mary of Burgundy, on the advice of her counsellor, devoted herself to skating on the canals under the bridges in Bruges. She skated for hours on end. One evening, however, she took a serious fall on the ice, possibly due to fatigue, that would permanently damage her health. She died a year later.

by van Aertgen van Leyden circa 1530.

from Hieronymus Bosch circa 1490

There is an often mentioned image from the end of the 15th century of the holy Lidwina of Schiedam on skates. The image is almost always quoted in Dutch and foreign literature as proof of the skate at the end of the 14th century. However, the skates shown only provide insight into the type of skates used at the end of the 15th century when the image was made. (Read also an extensive article about Lidwina van Schiedam by Nelly Moerman.)

We find a more detailed and truthful depiction of the skate in Hieronymus Bosch’s painting, ‘The Temptation of St. Anthony’ from about 1490. His skates are very similar to the 13th-century skates found in archaeological fieldwork.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Flemish and Dutch painters frequently created skating-genre paintings of winter landscapes. These themes are irrevocably linked to the fact that between 1550 and 1700 there was a colder period in the climate. This period is also referred to as the Little Ice Age. During this time the average winter temperatures were 1 to 1.5 degrees lower than current winter temperatures. Exponents of the genre depicting skaters in winter landscapes include Pieter Breughel the Elder (circa 1525-1569) who painted the ordinary-man, skating. The work of Pieter Breughel the Elder was continued after his death by, among others, his son Jan Breughel de Oude (1568-1625) and Joos de Momper (1564-1635). When Flemish cities fell before the Spanish ruler (1585), a number of artists fled to the free Republic in the north. In this way, the Flemish paintings valued in the North influenced the style and themes of painters in the Republic. It was Hendrick Avercamp (1585-1634) who set the tone with his detailed skating scenes in a winter landscape in the 17th century.

Through trade in Europe and overseas, the Republic prospered in the 17th century. The paintings of Avercamp evoked the image of a prosperous nation that amused itself on ice.

In the 18th century, after the Little Ice Age was over, winter landscapes with skaters took off as a genre in painting. In the 19th century when, in the arts, there was a romantic longing for the once powerful and rich Republic, the popularity of winter landscapes increased again. Painters such as Bisschop, Koekoek, Jongkind and Schelfhout frequently used skating scenes to give an extra Dutch dimension to their art products. At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century skating was also the subject of popular illustrators like Alb. Hahn and Joh. Throughout the 20th century, skating in painting no longer played a role. The genre then mainly occurred in photography.

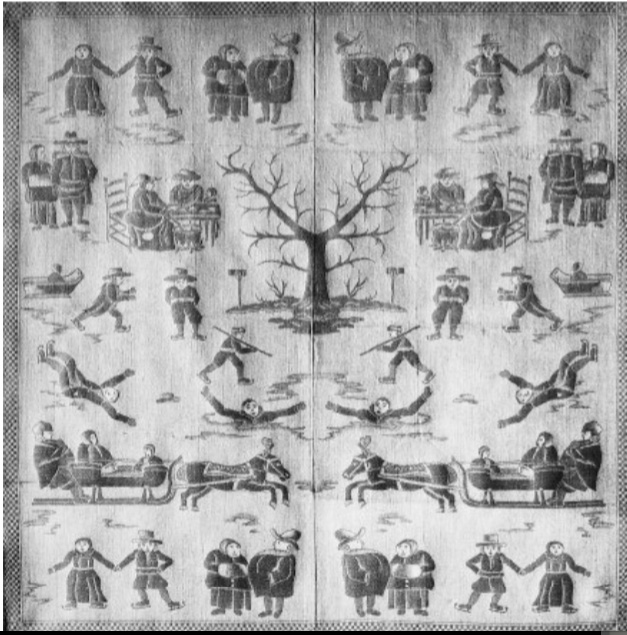

A special form of visual culture with a skating theme was painted tiles which had both a practical and decorative function in interior decoration. These illustrated tiles, measuring 13 by 13 cm, were used from the end of the 16th century to clad fireplaces- kitchens in particular. Regularly depicted, are skaters. Although the images were rather sketchy, the shape of the skates used is often quite easily recognizable. Another exceptional form of visual culture is the damask in which figures or images were woven on linen, silk or cotton. They were often used as table linen. Damask items were expensive and only used in higher circles. A beautiful example of skating scenes in damask is a napkin from Douwe van Aylva, grietman (reeve, a kind of mayor/Judge in Dutch villages before 1851) from West-Dongeradeel and his wife Luts Juliusd. van Meckema from 1662. It depicts various images showing fun on ice. The original is privately owned by the Abegg Stiftung, Riggisberg in Switzerland. A copy of it, which was created around 1950 by the Elias Linnenfabrieken in Eindhoven, is located in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Another example of the popularity of skating among the well-to-do is found in the inventory of the 17th-century dollhouse of Petronella de La Court (1624-1707), owned by the Centraal Museum in Utrecht. As the wife of the rich Amsterdam beer brewer, Adam Oortmans, she commissioned the production of this doll's house between 1670 and 1690. In the pantry she has a few miniature skates on the wall. The doll house itself shows the layout and interior of a rich family. Apparently, skates were a useful, basic item in a patrician family.

In the 17th and 19th centuries literature, like painting, skating themes reached a high point. National poets such as Bredero, Vondel and Cats praised skating in the 17th century. In addition, skating was associated with heroism and love. Heroic military strikes on skates were known in the fight against the Spaniards in Amsterdam (1572) and the siege of Haarlem (1573). Love themes showed skating as a leisure activity in which lovers woo-ed each other while skating. In the 19th century, as in painting, there was also a certain revival of skating themes in the literature. Patriotic writers such as Hasebroek, Beets and Bilderdijk are examples of this. In the twentieth century, after skating as a sport and leisure activity had completely broken through, skating was common in both prose and poetry.

An image of skating in the Netherlands can be obtained from both painting and literature. As a source for studying the development of the skate itself, painting yields more information than literature.

In painting, skating was regularly the central theme. Skates can often be recognized in paintings and prints. But rarely are the skates portrayed well enough for one to get a good idea of the design. In literature, skating was almost always subordinate to the central theme of novel or novella. In poetry, on the other hand, poems were regularly devoted entirely to skating. Only incidentally though, may you learn something about the skate itself. Generally, the terms used for the skates were irons or wooden.

Source

The article 'The oldest text is from Flanders, 1333' is written by Wiebe Blauw, a sponsor (member) of De Poolster. It has previously appeared in his book 'Van Glis tot Klapschaats' (2001)

Read more

More articles about the history of skating